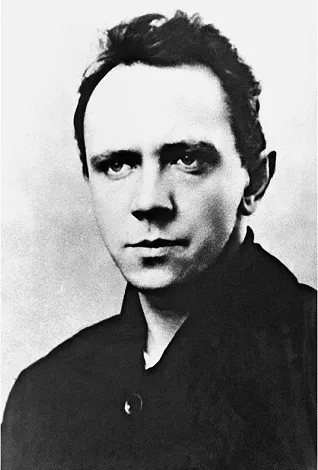

Plate 1 Michael Chekhov. 1920s

It is hard to write one’s autobiography at the age of thirty-six,* when life is far from over and when many of the forces which define one’s soul are just beginning to develop and come into consciousness as germinal seeds of the future. But if one has a more or less clear consciousness of these burgeoning soul-qualities and a certain understanding of where they are leading – if, moreover, one has the will to develop in this direction – it is possible to sketch a picture of one’s life which incorporates not only the past and the present, but also an ideal future. This ideal may never be fulfilled as precisely as one expects, indeed it probably won’t, but then again it will be a true picture of what a soul undergoing self-examination is experiencing in the present. †

* * *

Five or six years ago, I experienced a burning shame! I couldn’t bear myself as an actor, I couldn’t reconcile myself with the theatre as it was at the time (and still is now). I was clearly aware that whatever exists in both the theatre and its actors emerges as ugliness and untruth.1 I perceived the theatrical world as a vast, organized lie. Actors seemed to me to be the greatest criminals and deceivers. All theatrical life appeared to me as a sphere of huge dimensions, and at the very centre of this sphere a lie would flare up like a spark. The spark flared up at the very moment when the auditorium was full of people and the stage was full of actors. Between the stage and the auditorium a lie would flare up! At the same time, in the vast sphere of theatrical life, constant and tireless work was going on: books about the theatre, actors and directors, ‘seekings and strivings’, ‘experiments’, workshops, schools, lectures, reviewers, opinions, discussions, debates, arguments, raptures, enchantments and disenchantments, arrogance, immense arrogance, and alongside it money, titles, adulations, fear, enormous buildings scattered throughout the country, theatre personnel – with some honourable people amongst them, some semi-honourable and some thoroughly dishonourable. All these live, move, agitate, shout (loudly!), and impetuously fly from various points on the periphery of the sphere to its centre, where they resolve themselves into a flare, a spark, a lie! I could distinguish all the details of this overall picture with the greatest clarity. I saw the untruth, but as yet I did not see the truth. I looked with revulsion at myself – a participant in this great farce – and with horror at the farce itself. There was no way out.2

Like a large tableau, there unfolded within me and before me what I had experienced in my childhood and what I allow myself to remember here. In the first class in secondary school, I displayed an inordinate zeal for learning. My weekly reports shone with top marks. I was delighted with my success and with myself. Finally I was entrusted with the task of giving my fellow classmates some coaching in French. I was carried away by teaching and stopped learning myself. Some time passed. My pupils were summoned to the blackboard; they made mistakes, but no one thought to blame me. But then I was called up myself in order to show a pupil of mine where his mistake lay in writing ‘wous êtes’* on the blackboard. I came out and proudly wrote ‘wu zet’! The teacher froze! Something happened in that moment which I found both incomprehensible and dreadful. My world collapsed around me. The truth about me was laid bare not only for the teacher and my classmates, but also for myself. ‘Wu zet’! This is what my life in the theatre five or six years ago seemed to me to be like: I was burning with shame, but I didn’t know how to write these two little words correctly. The peak of my despair represented a turning point for me both as an artist and as a human being. From this peak, I shall try to cast my eye both backwards and forwards and attempt to connect my past with the future.

* * *

‘Mikhailo!’ – that’s what my father3 called me – ‘Mikhailo, go and weed the beds! All you do is play with toys! You little boy!’

But I really was very little and I had no idea why my father was reproaching me and why I couldn’t play with toys.

‘Drop everything – go and weed!’

I knew all too well what he meant by ‘weed’! It meant sitting in a bent position between the flowerbeds for hours on end without straightening myself out, tormented by backache and weeping tears of helpless anger at my father for having interrupted my game and for the pain in my back and legs. My physical health in childhood was not particularly good and I was extremely sensitive to any bodily suffering. But I was afraid of my father and I didn’t dare contradict him. He never hit me: anyway, it was not this that scared me about him. What terrified me was the power of his eyes and his loud voice. But for my father, fears and obstacles didn’t exist. Indeed, everything yielded to him. His immense will and physical strength made a profound impression – and not only on me. I really believe that when he sat me down for several hours between the flowerbeds, he couldn’t conceive that this might be a difficult task. He himself weeded for many hours without any visible fatigue.

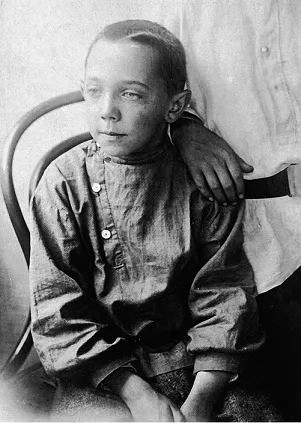

Plate 2 Michael Chekhov. 1900

But it wasn’t only fear that I felt for my father: I also respected and even revered him. Despite my youth, he would often expound all manner of philosophical doctrines to me in a remarkably engaging and accessible way, comparing and criticizing them. I listened with delight to what he said. His erudition was truly remarkable: he was thoroughly at home not only with questions of philosophy, but also with medicine, natural history, physics, chemistry, mathematics and so forth; he knew several languages and at the age of fifty he apparently learnt Finnish in two or three months.

But he was too much of an eccentric, and this prevented him from using his knowledge and great energy for life coherently and in some definite direction or other. He was biologically incapable of putting up with anything ordinary, habitual or conventional. So, for example, he couldn’t have just one pocket watch like everyone else, he had fourteen or fifteen of them; and the watches were not to be kept in the metal casings that ordinary watches have – no, the casings were removed from them and they were trimmed with thin pieces of board, carefully and skilfully jointed together. The clock on his wall was awful. It was made of corks, twigs, moss, wood lichens and similar things, with bottles full of water instead of weights, while on the floor next to it stood a magnificent old grandfather clock made of mahogany, which he apparently left untouched out of respect for its age.

My torment stemmed from the fact that I was drawn into almost all my father’s new inventions as his closest collaborator. I was once ordered to stir old newspapers in a barrel with a big stick, gradually adding water to them and turning them into a viscous mush. The idea was that this paper mush was spread out in a thick layer on the floor of his study and then, when it was dry, it was supposed to serve as a kind of linoleum. This was partly a way of saving money. He couldn’t reconcile himself to the fact that people pay for things that they can do themselves and, what is more, they can do cheaply. The work of pummelling newspapers lasted for several days. Then the paper mush was spread on the floor and finally emblazoned with a bright red colour, and at some later stage the cracked and warped ‘linoleum’ was stripped and scraped off the floor again.

In the spells between inventions, I avidly played in a constant state of haste and agitation. I still have the desire to do the things that I like and that give me pleasure as quickly as possible. My games were limited not only by time, but also by space. The whole yard belonging to our dacha* (we lived out of town† the whole year round) was taken up by a kitchen garden and a henhouse. My father’s hens were of the most diverse and unusual breeds and of such a delicate constitution that they could not endure the winter cold, and this caused my father a good deal of worry and agitation. His relationship with his hens was so complex and intimate that it was difficult to fathom. When the cock was not courting the particular hen that my father had designated for that purpose, then shouting and swearing would resound through the yard, the cock would rush away from my father appealing for help, the entire henhouse would fly into a state of agitation and my incensed father would withdraw into his study. But when the time came to load the incubator (the eggs were hatched artificially, of course), all the members of the household were stirred into action. The servants boiled the water, my brother4 carried the water into the room with the incubator, I watched the thermometer and the lamp, while my father laid the eggs out on some netting, marking them with the date, the breed of the hen, etc. And when after three weeks the chicks hatched, my mother5 and I had to go ‘tiu-tiu-tiu’ like a brood-hen, striking the table with our fingers right in front of the chicks, while my father invented all manner of devices which, by being lowered onto the backs of the entire family of new-born chicks, were intended to simulate for them the downy belly of the brood-hen.

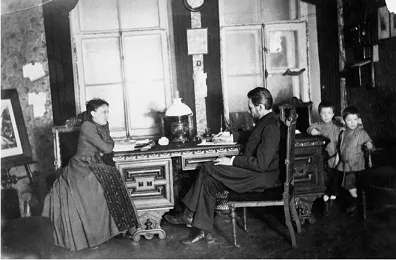

Plate 3 Natalya and Alexander Chekhov with Alexander’s sons from his first marriage, Nikolay and Anton. c.1890

Several times a year I had a happy interlude when I could play as much as I wanted – this was when my father went away. In fact, my father never actually went away; he suddenly disappeared and a few days after his disappearance my mother would receive a letter or a short telegram from him, saying, ‘I’m in the Crimea’ or ‘I’m in the Caucasus’. He loved travelling and he knew how to get about. He never took very much with him. He just threw a small camera bag over his shoulder, put a few items of clean underwear in it, took a stick in his hand and disappeared from the house.

My games were always passionate. Everything was exaggerated. If I built a house out of cards, it was not simply a house, but a colossal building occupying virtually the entire room, and my stilts would be of such a height that had I fallen off them, I most probably would not have gone unscathed. Playing fireman also took on grandiose and dangerous proportions. But at the same time I was not exactly renowned for my courage.

My father’s disappearances were a source of great joy for me, but his returns home were sad. Sad – because he returned unwell. He suffered from heavy bouts of drinking, which exhausted him physically and morally. His disappearances were a tormenting struggle for him against these oncoming attacks. His colossal will-power held back the onset of the illness for a long time, but it always overcame him, and burning with shame and tormented on account of my mother and myself, he would quietly say with pain in his voice:

‘Mother dearest, send for some beer.’

My mother never protested or tried to influence him; she knew and saw how he himself was in torment. And here destiny (and perhaps he himself too) played a trick on my father: he was the author of some books on the subject of ‘Alcoholism and How to Fight It’. Professor O.* – a man well known in his day, who treated alcoholics by hypnosis – offered my father his services on many occasions.

‘I wouldn’t bother, old chap,’ replied my father with an ironical smile, ‘nothing will come of it.’

But O. insisted, and on one occasion my father agreed to try hypnosis. He and O. sat opposite one another, and – if my memory does not deceive me – O. quickly dozed off under my father’s gaze.

One of the consequences of being with my father in the periods of his illness was that I too started drinking.

In the first days of his illness, my father would go around the haunts and night tea-rooms of the locality in which we lived, conversing with rogues, thieves and hooligans and distributing money to them. His popularity in their circle was considerable. They loved and respected him – and not only for his money, but also for the conversations that he had with them.

Whenever the local hooligans passed our dacha, they would often say to me or my mother:

‘A good day to you! Don’t worry, we won’t touch you!’

And they never did.

There dwelt within my father a spirit of protest against the social conditions of the time. But he expressed this protest in a distinctivelyindividual and rebellious way. For example, he would hold out his hand demonstratively to a policeman in the street so as to arouse a sense of indignation and resentment in the powerful people of this world, and he would go to see people of importance in a wholly inappropriate form of attire.

Whenever my father’s illness seized hold of him, my inner life would take on a rather different character. On the one hand I suffered both for my father and my mother, and on the other hand I rejoiced at the attention which my father showed me during his illness. He told me many remarkable things and whatever he said would become irresistibly fascinating. He knew how to write and speak simply, powerfully, colourfully, intelligently, captivatingly, and when necessary, wittily. Anton Chekhov said of him:

‘Alexander is far more able than I, but he will never do anything with his talents – his illness will ruin him.’

I would sit for hours beside my father, listening to what he was saying about the world of the stars, the movement and structure of the planets, the signs of the zodiac and so on. He introduced me to all manner of phenomena and laws of nature, illustrating them with the most unexpected and beautiful examples. We never touched on religious themes, for my father was an atheist and had a materialistic concept of the world. He inculcated in me a love of knowledge, but all my attempts at studying philosophical systems or particular sciences w...