![]()

Chapter One

Self-Made Men

Temperance, Identity, and Authority in Antebellum America

When historians have considered the antebellum temperance movement, they have often described an icon of antebellum America itself, the self-made man. He was white, upwardly-mobile and individualistic. During the day, he competed in a market economy to get ahead, and at night, he returned home to a domestic, feminine oasis from the capitalist fray. A total abstinence lifestyle was a natural choice for such a man. The temperance movement made alcohol a readily identifiable source of failure, which soothed the anxiety surrounding a man’s personal fortunes and eased his conscience regarding those who enjoyed none of their own success. He could assure himself that he would not slip into poverty if he simply abstained and that those who did slip must have done the opposite. The total abstinence lifestyle also made him a model father and husband in the sentimental, middle-class home.1

Although temperance literature from the time bears out this interpretation, it also speaks to the complexities and tensions within the character of the self-made man.2 Certainly, the dominant image of the movement during these years was white, male, and middle-class; the overall message of the antebellum movement was one of male achievement, authority, and mastery. But the deeper story of the relationship between temperance and the self-made man was one of class, gender, and racial identities in flux. In antebellum America, temperance became a way of discussing these issues and constructing these identities.

Temperance, in its original form, was not an antebellum creation. Reformers first touted the idea that alcohol was a major problem in the nation’s culture as early as the 1780’s. With the necessity of virtuous citizens for the new republic and rising alcohol consumption, it is not surprising that Americans’ awareness of the issue increased in the wake of the American Revolution.3 In 1784, they saw the first scientific evidence that alcohol could potentially destroy human health and happiness when Dr. Benjamin Rush published An Inquiry into the Effects of Spiritous Liquors on the Human Body and Mind. The next few decades witnessed the birth of dozens of temperance organizations, led by society’s elites and dedicated to promoting moderation in drink, both for its members and the larger society.4

The formation of the American Temperance Society in 1826 marked a changed direction for the movement and the start of its life as the most widespread and enduring reform movement in American history. The ATS loosely coordinated temperance activity throughout the country, sending out paid agents as traveling lecturers, printing and distributing temperance literature, and encouraging the establishment of temperance societies. The results were spectacular; by the next decade, the ATS boasted five thousand state and local societies and more than a million members, each of whom had taken a pledge of total abstinence from most forms and usages of alcohol.5

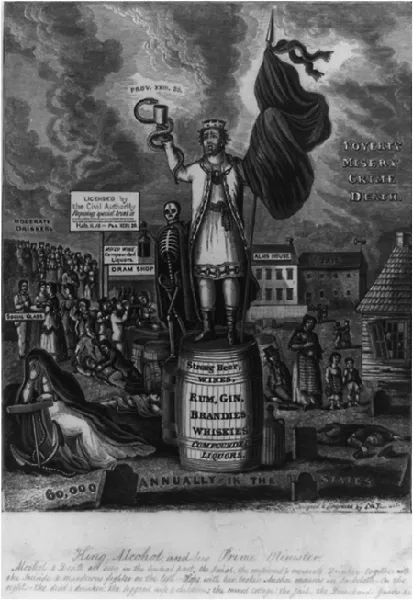

By the time the ATS transformed temperance into a mass movement, the nation was in the throes of “the market revolution,” the economic shift to a capitalist economy and the concomitant social and political shift towards greater individualism and democracy.6 As part of this larger transformation, the Second Great Awakening provided an important spiritual impetus for the antebellum movement. Temperance easily melded with the Awakening’s democratic impulse, as it created extra-denominational rituals that served as alternatives to the authority of established churches. And the message of antebellum revivalism provided a powerful religious impulse behind temperance, particularly as it emanated from millennial hopes for American society. In Lyman Beecher’s Six Sermons on Temperance, delivered in 1825 and credited as a precipitating event for the formation of the ATS, he singled out alcohol as “the sin of our land” that threatened to “defeat the hopes of the world.”7 As it encroached upon the lives of individual citizens and turned them into loathsome, irrational, and poverty-stricken drunks, alcohol threatened to stunt the political, economic, social, and moral progress of the nation, defeating all utopian possibilities. Like other perfectionist reforms that emanated from religious trends, temperance linked individual perfectibility to that of society. If individuals purged their own lives of alcohol’s detrimental effects, the nation, and even humanity as a whole, might be elevated.8

Although temperance had this broader, cultural component, in the antebellum years, it was deeply and preeminently personal for its participants. Scholars agree that temperance was particularly dear to the burgeoning middle classes. Those classes appropriated the movement from its earlier elitist leadership and re-made it into an individual pursuit of total abstinence, which, writ large, would eventually and completely eliminate alcohol from national life.9 The middle classes employed the movement to shore up their own position in society and to negotiate their own class identity—neither of which were certainties. As historians have most recently demonstrated, the middle classes often moved back and forth on a broad trajectory between poverty and wealth, employee and employer, manual labor and professional work. In addition, far from being unapologetic creations and beneficiaries of capitalism, the middle classes often expressed, in word and behavior, mixed feelings about the culture of the market; they at once strived to succeed within it and disapproved of its core values. Temperance discourse revealed the ambivalence and contentiousness of middle-class culture and aided its resolution.10

On a purely practical level, total abstinence from alcohol was a defensive strategy against the threat of poverty—a constant theme in antebellum temperance literature. A leading temperance newspaper of the 1830’s so believed in the success reaped from abstinence, it called temperance societies “savings banks” and claimed their members were “making money…. Every citizen is cordially invited to share the gains with us.”11 Horace Greeley, a temperance advocate throughout his career, saw such principles operating in his own family; he attributed his parents’ “pecuniary ruin” to their use of “ardent spirits and tobacco—very moderately, they think, but greatly to their injury, I know.”12 Temperance fiction often exploited the fear of poverty in promoting total abstinence. “History of Peter and John Hay” narrated the experience of two brothers living the liberal American dream, who eventually became “slaves of intemperance,” lost all, and died horrible, drunkards’ deaths.13 The Story of James and Mary Duffil: A Tale of Real Life (and most other temperance stories) had only a change in cast.14 Such temperance tracts struck at the heart of middle-class fears by warning, “If you are determined to be poor … to starve your family … to blunt your senses, be a drunkard, and you will soon be more stupid than an ass…. You [will] be dead weight on the community.”15 A man who failed to provide for himself and his dependents was “useless, helpless, burthensome and expensive.”16

As these examples reveal, the middle-class fear of poverty was not simply a terror of individual failure but a betrayal of community.17 Peter and John, for instance, were not self-made but instead attained success “by wisely improving the fruits of their father’s labors.”18 And though middle-class promotion of temperance has often been portrayed as a shrewd, if unconscious, business tactic for securing a disciplined, productive work force, there is just as much evidence that middle-class Americans employed

temperance to further communal values, not just individual gain.19 Consider, for instance, a tract entitled “The Well-Conducted Farm,” which told the story of a Massachusetts farmer who forbade his workers to drink. The tract certainly boasted that the farm made more money. But it also claimed, “The men appeared, more than ever before, like brethren of the same family, satisfied with their business, contented and happy.”20 The story demonstrated a longing not just for individual wealth and success but for more republican ideals of community and virtue, values that eroded under the onslaught of individuals striving to succeed.21

Reformers sometimes revealed a deep distress that economic progress in some cases came at the price of these values. Nowhere is this attitude, and middle-class ambivalence about the market, more clearly evident than in the depictions of those who made their living from the sale and manufacture of alcohol. Rumsellers and distillers were entrepreneurs themselves and, in a sense, models of middle-class striving and success. In temperance literature, the rumseller was often a pillar of the community, a deacon or at least a church member. Reformers expended great effort to lift the veil of respectability from these men and to expose them for what they believed they were, those who sacrificed the good of society for their own wealth. They had particularly strong words for those who called themselves Christians, claiming that if they could see their trade through the eyes of God, they “would sooner beg your bread door to door, than gain money by such a traffic. The Christian’s dram shop! Sound it out to yourself…. It is doubtless a choice gem in the phrase-book of Satan!”22 It was unfair that the drunkard bore all the shame of intemperance, while “men will bow to [the rumseller] and seek his acquaintance, though he has proved to one person, if no more a robber and a murderer!”23 Indeed the “hardihood, effrontery, and shameless audacity of Rumsellers is unparalleled by any other class of the vile and abandoned on earth.”24

The attacks by middle-class reformers on middle-class rumsellers potently revealed the tensions within middle-class culture. Even while temperance discourse proclaimed the cause would aid pecuniary success and even portrayed it as a moneymaking enterprise, it expressed discomfort with the pursuit of material gain at any cost. Rumsellers disgusted temperance folk because they epitomized the values of the marketplace in a society that tried to temper cultural change with the preservation of republican values; they revealed how tenuous the balance was between material and moral progress. Dealing in alcohol offended because “its sole reason is to make money. It is not because it is supposed that it will benefit mankind…. It is an employment which tends to counteract the very design of the organization of society.”25

Such objections to the capitalist enterprise of the alcohol industry can be interpreted in two ways. On the one hand, one might argue that middle-class reformers employed alcohol as a scapegoat that allowed them to ignore the larger problem of the market’s impact on social values. But one might also argue that temperance reformers leveled a meaningful social critique of unrestrained capitalism. Either way, however, temperance discourse in this instance speaks to the nuances of middle-class culture and its relationship to the market revolution. It also helps explain the appeal of temperance for the middle classes, as it at once warded off poverty and emphasized the sin of pure material pursuit. At both ends of the spectrum, individual behavior affronted the values of community. Middle-class Americans, by choosing to abstain, might set a powerful example and “change the habits of a whole nation.”26

The tension within middle-class culture between the competing values of the market and a republican social order was often expressed in gendered terms and contained gendered dimensions, as those competing values became sexualized in the antebellum mind. Historians have all but dismantled the notion that nineteenth-century men and women resided in “separate spheres” by demonstrating the involvement of even middle-class, white women in politics and business. Contrary to earlier historical interpretation, as the household economy eroded (which in itself occurred unevenly and over a protracted time span), women of the new middle classes were not quarantined to isolated, domestic enclaves. In truth, the middle-class home was no oasis from the market; it was the scene of market consumption and oftentimes business transactions (such as boarding arrangements), both conducted chiefly by women. Nor were women confined to the home. They attended political rallies and parades, sat in the galleries of Congress, ran benevolent organizations as businesses, and sold their handcrafted goods at fairs. Even women in wealthy, hierarchal, southern households engaged in these activities and served an economic function within the home, such as the management of domestic slaves.27

Although gendered sphe...