1: Future, time and education: contexts and connections

The futures context

Knowledge about the future or even futures is, like any other knowledge, ‘rooted in a life, a society, and a language that [has] a history’ (Foucault 1973:372). As we cannot know something which has not yet happened, knowledge about the future comprises ideas and assumptions about the future, images and visions of the future as well as the investigation of causalities that bring the logical consequences of certain events and trajectories. Given that the future is not predetermined, every study of the future is ‘strictly speaking, the study of ideas about the future’ (Cornish, cited in Wagar 1996: 366). It is an inquiry, or ‘the study of possibilities that are plausible in terms of present-day knowledge and theory’ (ibid.).

The previous and the following discussion on social and educational change arise from the particular tradition of investigating the future or from ‘modern futures studies’. This multidisciplinary and systematic field of inquiry of probable, possible and preferable futures that emerged in the twentieth-century western world is based on the following key philosophical assumptions:

- The future is not predetermined and cannot be ‘known’ or ‘predicted’.

- The future is determined partly by history, social structures and reality, and partly by chance, innovation and human choice.

- There is a range of alternative futures which can be ‘forecast’.

- Future outcomes can be influenced by human choices.

- Early intervention enables planning and design, while in ‘crises response’ people can only try to adapt and/or react.

- Ideas and images of the future shape our actions and decisions in the present.

- Our visions of preferred futures are shaped by our values.

- Humanity does not make choices as a whole, nor are we motivated by the same values, aspirations and projects (Amara 1981; Bell 1997; Cornish 1999; De Jouvenel 1996; Fletcher 1979; Masini 1993a; Slaughter 1996a).

More specifically, the theoretical approach in this book follows the ‘critical/poststructural’ and ‘cultural/ interpretative’ (Inayatullah 1990) tradition within modern futures studies. It also provides an analysis of ‘normative’ (Moll 1996) approaches. The critical/post-structural approach expands the discourse of the future across cultures, and ‘by historicizing and deconstructing the future, creates new epistemological spaces that enable the formation of alternative futures’ (Inayatullah 1990:115). To contest the given future and create alternative futures, critical futures thinking is crucial as it helps us recognize that every approach to educational change is inherently based on an underlying image of the future (and of time). The normative approach incorporates utopian and imaginative thinking, visioning and the consideration of social and cultural dynamics (Moll 1996:18).

In addition, theoretical influences include three distinctive and overlapping approaches within social sciences—postmodernism, feminism and postcolonial theory. The inquiry focuses primarily on the western and patriarchal imprint on the dominant futures visions, on alternatives that have developed outside and on the margins of the western paradigms as well as within women’s/ feminist movements. Deconstruction, genealogy, critical discourse (methods which have become increasingly familiar) and causal layered analysis (CLA) are used in order to investigate how particular ideas and images about the futures of education have become dominant— the accepted norm—and thus now frame what is possible.

Causal layered analysis, developed by Inayatullah (1998a), enables analyses of how data within various discourses are contextualized, interpreted and located in ‘various historical structures of power/knowledge— class, gender, varna [caste] and episteme (the critical)’ (ibid.: 816). CLA complements methods that focus on the horizontal spatiality of futures discourses, such as scenarios, back-casting and emerging issues analysis. It focuses on the vertical dimension of futures studies (ibid.: 815) and takes a layered approach to the future (Slaughter 2002). This layered approach to the future, as developed by Inayatullah, consists of four levels. These four levels are:

- Litany—the description or visible characteristics of the issue. The trends and problems that are often exaggerated and used for political purposes are part of the public debate.

- Social cause—qualitative interpretation of data and economic, technological, cultural, political and historical systemic factors are explored.

- Discourse/worldview—focuses on finding deeper social, linguistic, temporal, cultural structures and the discourse/worldview that supports them.

- Myth/metaphor—consists of deep stories, collective archetypes, the not-so-apparent-and-obvious dimensions of the problem under inquiry (Inayatullah 1998a).

As a critical futures studies method, CLA asks what layers of understanding are missing from conventional trend analysis (linear futures). It seeks to explore the politics of knowledge and meaning nested in conventional statements of the future. It intends to go beyond the litany of statements (e.g. ‘the Internet will revolutionize education’) by asking which social, economic and political causes and factors can create revolutionary change in pedagogy. Moreover, it asks who has access to power, in this example, to the Internet. At a further level, issues of worldviews and discourses (e.g. feminist, non-western) are explored. In the case of the Internet and education, it considers the ways in which the Internet is a representation of instrumental rationality. How does it privilege sense-based education and avoid knowledge that comes from spiritual modes of learning? At an even deeper level, constitutive myths and metaphors are explored. For example: Is education mainly about the speed of access to information, or is education predominantly about inner transformation, as with spiritual education? Is the purpose of education mainly to control, achieve and compete, or is its purpose mainly for the improvement of the self (as in eupsychia) or society (as in utopia)?

These approaches acknowledge that various individuals, communities and civilizations all have their own ‘futures knowledge base’— that is, the way they see and understand time—as well as their own assumptions and visions about the future. These are neither universal nor ahistorical as they vary through space and time. However, in our current world there are also many commonalities and similarities. For example, there is hardly any geographical or psychic space left that is not being imprinted with both western modernist views of progress and development, and western educational models. Still, various local sites all have their own ‘regimes of truth’ about social and educational futures; that is, they are not free from exercising their own hegemonic future visions. However, this book focuses on the manifestation of hegemonic visions of the future that imprint on the global—and English-dominated—space, and alternatives that contest this hegemony. Hegemony is here used in terms of Gramsci’s notion designed to explain how a dominant class (or social group) maintains control by, as Lewis (1990) describes it:

projecting its own particular way of seeing social reality so successfully that its view is accepted as common sense and as part of the natural order by those who in fact are subordinated to it [Jaggar 1983:151]… In this respect, hegemony is accomplished through an ongoing struggle over meaning not only against, but for the maintenance of, power.

(Lewis 1990:474)

So, the following section asks which view of time and of the future is currently hegemonic—taken for granted, accepted as common sense and as part of ‘the natural order’? More importantly, how and why has this happened?

Civilizational approaches to time

Conception of time and the future exists in every known society (Bell 1994). The practice of divination, rites of passage (transitions to future social roles), agricultural planning, seasonal migrations, development of calendars all testify that ‘conceptions of time and future exist—and have existed—in human consciousness everywhere’ (ibid.: 3). The future is ‘an integral aspect of the human condition’, because ‘by assuming a future, man makes his present endurable and his past meaningful’ (McHale 1969:3).

Although the conception of time and the future exist universally, they are understood in different ways in different societies. Masini (1996:76) argues that there are three main representations of time. The first representation is:

A variation of cyclical motion, as in the enclosed circle of life and death in living organisms, or of night and day in cosmic time. This representation is well reflected in the Hindu and Buddhist ‘cosmic eras’ (kalpa) which are delimited by mythological events in time periods through which all beings continue ad infinitum.

The cycle is represented by a snake. In this conception we see the future as part of an unending continuum. The future is part of life and death. Naturally this influences one’s perspective of the future: there is little reason to despair or to strive to achieve.

(Masini 1996:76)

The second representation is based on the Graeco-Roman and the Judaeo-Christian conception of time:

Founded on the idea that all people are the same in relation to God. Time is perceived to be a trajectory towards something more, towards accomplishment. In this representation time is symbolized by an arrow; the future is better than the present and the past and may be in contradiction to the historical present, as in utopia. The possibility of the future being worse than the past or present is out of the question. This is the conceptual base of ‘progress’…the time of scientific and technological development, where every success has to be bigger and better than anything in the past or present…(but) this concept of time and the future is being challenged by environmental barriers and barriers emerging from its own frame of reference.

(Masini 1996:76)

The third representation has been developed, according to Masini, by Vico and others and has been extended by Laslo (ibid.: 77). According to this representation, ‘Time is a spiral, an evolutionary process of world civilization giving a structure to spatial and temporal events ranging from the natural to the social, that develops over time’ (ibid.).

These three basic metaphors for time—circle, arrow and spiral— influence the type of futures thinking— and the very understanding of the future—across cultures. Sohail Inayatullah writes:

Different visions of time lead to alternative types of society. Classical Hindu thought, for example, is focused on million-year cycles. Within this model, society degenerates from a golden era to an iron age. During the worst of the materialistic iron age, a spiritual leader or avatar, rises and revitalizes society. In contrast, classical Chinese time is focused on the degeneration of the Tao and its regeneration through the sage-king seen as the wise societal parent.

(Inayatullah 1996:200–201)

What is missing from Masini’s discussion on the three main representations of time is an understanding of time as ‘non-flowing’, as part of an ‘eternal now’ or as ‘Dreaming’.1

Having western and some eastern societies in mind, Masini further argues that while some cultures have focused on development and progress of the society, others have focused on the development of the self— an ‘accomplishment of the ideal person’ (Masini 1996:77). Views of time and the future have practical implications for individual and social lives. For example, different views of time and the future seem to have contributed to some societies (e.g. those based on the Judeo-Christian tradition) developing in accordance with the expansion principle, and some (e.g. many indigenous societies) in accordance with the conservation principle. Thinking about time and the future is an integral part of cultural and civilizational worldviews, which in many ways determine particular directions, decisions and choices that are made.

This enunciation of four approaches to time does not mean that the linear concept of time is exclusively western, the cyclical inclusively eastern and eternal time exclusively indigenous. Temporal structures should not be essentialized. Adam (1995:29), in particular, warns about social construction of ‘other’ time, based on a division between ‘them’ and ‘us’. The recognition that the experience of time is integral to human existence, but that the way we perceive and conceptualize that experience varies with cultures and historical periods, underpins all studies of ‘other’ time (ibid.). These anthropological, historical or sociological studies recognize that ‘the meanings and values attributed to time are fundamentally contextdependent’ (ibid.). But they also ‘dichotomize societies into traditional and modern ones in which the time perception of the former is constructed through its opposition to the dominant image of “our Western time”‘ (ibid.). ‘Other time’ thus becomes the ‘frozen present of anthropological discourse’ (ibid.: 30). The main problems with this are that ‘alien’ time is ‘commonly explicated in terms of what it is not, and that the existing dualistic models of “own” and “other time” are fundamentally flawed’ (ibid.: 30). But any analysis of ‘other time’, concludes Adam (ibid.: 31), is also a ‘simultaneous commentary on “our time”‘. Thus, what is important to mention here is that each of the three civilizations that I next analyse understands, or has understood at some point, that all three ‘times’ are inherently interwoven together. The concept of time can only be derived from the concept of change, composed observationally and relationally (Lippincott 1999; Prasad 1992). Experiences of linear and cyclical movements, as well as feelings of eternity, are all universal human experiences. Most importantly, this division does not imply in any way that ‘cyclical’ and ‘eternal time’ are to be found only in previous historical periods. As I will argue in Parts III and IV, many alternatives, many current educational visions are based on these alternative ‘traditions’ rather than on linear ones. In that sense, both cyclical and eternal time can still be found, or, alternatively, can still be ‘reinvented’ or ‘reconstructed’ to suit present issues and dilemmas. Time is thus, or can be, a resource—not an independent variable—to be used to create other futures. Some of the alternatives do exactly that: use different approaches to time to argue for a new (even a meta) narrative about the future. This is extremely important, because if the dominant views of time and the future remain uncontested, the discourse remains controlled and managed by dominant social and cultural frameworks of meaning. The transformation of educational structure, process and content becomes almost impossible. What critical futures thinking enables is the recognition that there is an underlying image of the future in every educational change approach.

It is also important to stress here that although various experiences of time are indeed based upon universal human experiences, the way in which time is experienced is also ‘profoundly influenced by theories or beliefs about the nature of the world’ (Morphy 1999:265). It is both this experience of time and a particular ontology that have always influenced education in a particular way. Though rarely explicit, ‘teaching time’ has always been part of a ‘hidden’ curriculum. Both current educational practices and all educational visions for the future significantly incorporate this hidden curriculum.

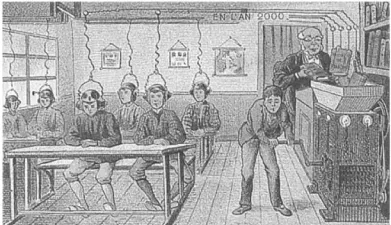

Hidden curricula: The dominant view of the future and approach to time

Over the last 500 years—with the help of the expansion principle intrinsic to capitalism and colonialism, and the way ‘progress’, ‘development’ and ‘time’ were seen and defined—the ‘victory’ of western models of civilization has occurred. This hegemony of western civilization has also meant the implementation and imposition of western concepts of time (time being linear) and of the future globally (e.g. the idea of ‘millennium’), and, as we will see in the following section, western models of education. Futures thinking thus became linear, concerned with progress and with ways for controlling the future. ‘Science’, including ‘social sciences’, developed within this context.

The roots of the current linear understanding of time lie within both Christianity and modern science. In the Christian view, God has created the world and at some point. He is going to bring it to an end (Taylor 2001). The scientific view of the universe follows a strictly linear pattern. Time is divided into past, present and future and into hours, minutes and seconds. The Universe was created in a Big Bang and either it will end in a Big Crunch or, after it expands indefinitely, it will slowly fade away. In the end, reports Lemonick of Time magazine (2001:52), the universe—’once ablaze with the light of uncountable stars’—will become an unimaginably vast, cold, dark, empty and profoundly lonely place. Since no biological matter can escape, the only consciousness that can possibly survive could perhaps be in the form of a ‘disembodied digital intelligence’ (ibid.). It is this view of time that is behind some futures alternatives, such as that of globalized cyber education. I discuss this in more detail in Part II: Destabilizing dominant narratives, which deals with dominant futures and utopian visions.

The linear movement of time is implicit in current notions of progress and its reverse image, regress. When the linear future is understood as regress, a certain historical period from the past is idealized as a more, or the most, desirable way of living. One example is ‘back to the basics’ demands that idealize the mid-twentieth century in countries such as the USA or Australia...