eBook - ePub

The Romanization of Central Spain

Complexity, Diversity and Change in a Provincial Hinterland

This is a test

- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Romanization of Central Spain

Complexity, Diversity and Change in a Provincial Hinterland

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Curchin explores how, why and to what extent the peoples of Central Spain were integrated into the Roman Empire during the period from the second century BC to the second century AD.

He approaches the question from a variety of angles, including the social, economic, religious and material experiences of the inhabitants as they adjusted to change, the mechanisms by which they adopted new structures and values, and the power relations between Rome and the provincials. The book also considers the peculiar cultural features of Central Spain, which made its Romanization so distinctive.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Romanization of Central Spain by Leonard A. Curchin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

1

INTRODUCTION

History is a fraud, a subjective interpretation of events accepted as objective truth.

(Eliot Hayes)

For every problem there is one solution which is simple, neat, and wrong.

(H.L. Mencken)

What was it like to be a Celtiberian in the Roman world? This simply-stated problem evokes more questions than answers. What do we understand by ‘Celtiberian’ and ‘Roman’? Would Celtiberians under Roman rule still think of themselves as ‘Celtiberian’, or as ‘Roman’? And to which phase of the Roman world are we referring: the second century BC, the age of Augustus, the Late Empire? Then again, is our hypothetical Celtiberian male or female, rich or poor, urban or rural? Would such a person still be living in Celtiberia, or would they profit from the employment opportunities and material comforts available on the Mediterranean coast of Spain, or at Rome itself?

Previous generations of scholars neither asked nor cared how a Celtiberian would have reacted to being part of the Roman world. But in recent years, the research agenda for Roman history has shifted dramatically. The focus is no longer on consuls and battles, but on long-term trends and socio-cultural issues. Traditional historical questions arising from the annalistic ancient sources have yielded their primacy to such unconventional concerns as demography, gender studies and economic modelling. In this altered climate, the study of Romanization must embrace new techniques and consider new themes, including human behaviour, personal and group values, and the construction of identity. Though historians still find it convenient to objectify the elements of Romanization as cities, religion, language, and so on, these are not so much ‘things’ as reflections of human activity. Cultural transformation is really about changes in people’s behaviour.

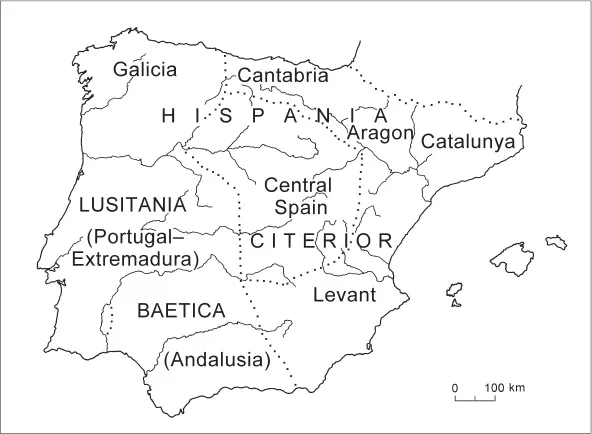

Regional studies, both in Italy and in the provinces, have proved highly remunerative in revealing the dynamics of Romanization. Each provincial territory had its own physical environment, its own indigenous culture, and its own history of relations with Rome, all of which affected and modified the Romanization process. It is only through studying the provinces, and the diverse peoples and cultures they embraced, that we can understand the workings of the Roman empire. At the same time, as Blagg and Millett (1990: 43) have pointed out, ‘a Roman province may be too large as a suitable area for analysis’. Such is surely the case with Hispania Citerior (also known as Tarraconensis), the largest of Rome’s European provinces, which stretched from the Mediterranean shore of eastern Spain to the Atlantic coastline of Cantabria and Galicia. Central Spain, the geographic heartland of Citerior (Figure 1.1), differed from the coastal regions not only in its elevated inland position but in its ethnic, linguistic and cultural background. Indeed even within this region, the homeland of six indigenous peoples (the Celtiberi, Arevaci, Pelendones, Turmogi, Vaccaei and Carpetani), we encounter a wealth of cultural diversity. Given its insular location and peculiar cultural traditions, Central Spain provides a remarkable laboratory for the study of cultural change in the Roman period.

Figure 1.1 Location of Central Spain, in relation to Roman provinces and modern regions.

Compared with the surrounding areas, Central Spain has been largely neglected except by local scholars, whose writings rarely treat the region as a whole and are practically unknown outside of Spain. Books dealing with Celts or the European Iron Age tend to concentrate on north-west Europe and to ignore Central Spain. Roman specialists living outside of Spain seem particularly uninformed about this region. For instance, Cabeza del Griego (CU) is identified by one modern writer as ancient Ercavica (Dyson 1985: 195), while another decries its ‘lack of substantial buildings’ (Fear 1996: 261); yet the site has been securely identified as Segobriga for more than a century, and boasts a well-preserved theatre (still in use today), amphitheatre and baths. Years of excavation throughout this region have turned up enormous quantities of archaeological sites and artifacts, yet these are of little use unless we can apply them to a specific problem.

The essential research problem of this study is how, why and to what extent the peoples of Central Spain were integrated into the Roman empire. This question will be approached from a variety of angles, including the social, economic, religious and material experiences of the inhabitants as they adjusted to change, the mechanisms by which they adopted new structures and values, and the power relations between Rome and the provincials. An attempt will also be made to indicate the peculiar features of Central Spain that made its Romanization distinctive. The period under consideration runs from the second century BC to the mid-third century AD. While Central Spain was certainly Roman during the Late Empire, and the process of acculturation with Roman society continued, the formative period of Romanization was the Late Republic and Early Empire. As is well known, the world of Late Antiquity bears little resemblance to its predecessors, and has its own peculiar problems of source material. In Central Spain, the late period is represented almost solely by villas and cemeteries, which hardly provide an adequate basis for documenting cultural change. The history of Central Spain in the Late Empire certainly merits treatment, but in a separate study.

It may be asked why I have not included the middle Ebro valley, especially the district around Contrebia Belaisca (Botorrita, Z) which has yielded important inscriptions in the Celtiberian language. My study area, however, has been selected for its geographic unity and its relative isolation from the Mediterranean world. Naturally Central Spain had contacts and cultural ties with neighbouring regions such as the Ebro valley (which has easy access to the Mediterranean) and Lusitania (site of the Celtiberian mint of tamusia), but there are practical limits to how much can be covered in one volume. The Romanization of Lusitania and of the Ebro valley deserve studies of their own. All the same, Central Spain did not exist in a vacuum. It was part of Roman Spain and, in turn, of the Roman empire. Though my main interest has been to show how the residents of this region adopted or adapted Roman structures and lifestyles, I have, where it seemed helpful, indicated how Central Spain differed from the more (though not completely) Romanized cultures of southern and eastern Spain. Nevertheless, space does not permit a comprehensive interregional analysis of the Iberian Peninsula.

An austere land

Endless, and just like the mirror of the sea, stretch the plains of the Castilian plateau. It is a poor land. The meagre soil, mixed with stones, produces only sparse grain, and the scarcity of water inhibits any other cultivation. Only seldom will the eye delight at green foliage on the edges of a spring or stream; even less often at a small stand of pines or cork-oaks. Sparse also are the human settlements: small villages built from the mud of the soil, and scarcely discernible from a distance …

(Schulten 1927a: 5)

Renowned thinkers from Montesquieu to Braudel have preached environmental determinism, the theory that people’s behaviour is affected by regional environment (Peet 1985). This theory has since been challenged in favour of a notion that human culture shapes the landscape, and that environmental resources offer many possible options for human adaptation (Sauer 1963: 343; Horden and Purcell 2000: 410–11). The new perspective rightly privileges human agency and initiative over the impersonal effects of nature. Yet it needs to be remembered that environment not only offers but may also limit choices of adaptation strategy. Such limitations are less apparent today, when technology enables people to live productively in Antarctica, the desert or outer space, than in ancient times, when society had fewer mechanisms for adapting to the terrain, climate, soils, minerals, flora and fauna of their surroundings. Pre-industrial reality is perhaps best summed up by the Mohawk proverb: ‘The people do not make the land; it is the land that makes the people’.

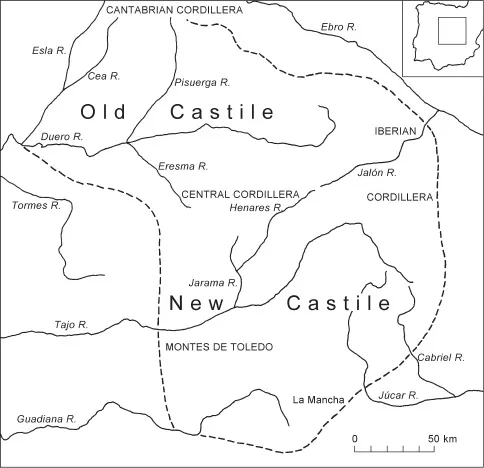

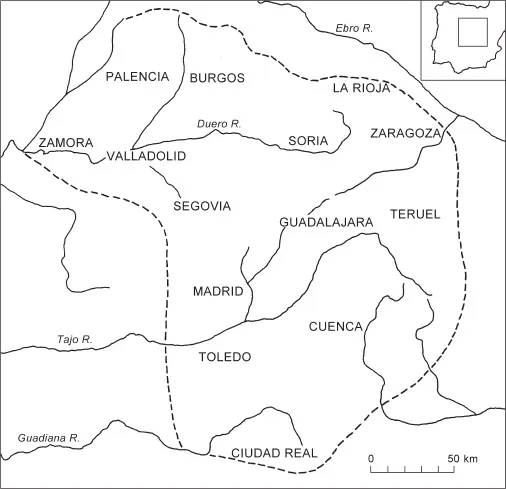

The impact of the geographical matrix is particularly vivid in the Iberian Peninsula, whose highland and lowland regions present extreme differences of landscape, vegetation and weather patterns. While the Mediterranean littoral has always been the richest and most densely settled area of Spain, it is the barren Castilian uplands that form the heartland of the Peninsula. Central Spain consists of an extensive tableland, divided into northern and southern sectors by a mountain range known as the Central Cordillera (the ancient iuga Carpetana) running diagonally from north-east to south-west (Figure 1.2). On the north and east, two long mountain ranges (the Cantabrian and Iberian Cordilleras, the former being an extension of the Pyrenees) effectively isolate our region from the damp Cantabrian coast and the temperate Ebro river valley. Because the plateau of Central Spain slopes more gently towards the west and south, the regional limits on these sides are less easily defined. On the west, however, the Romans established territorial boundaries which, coinciding with pre-Roman ethnic divisions, provide convenient demarcations for the period under study (Figure 2.2). The eastern border of the Roman subprovince of Asturia et Callaecia, which at the height of the Empire had its own procurator and its own juridical legate, divided the Astures from the Vaccaei. Further south, the provincial border between Lusitania and Hispania Citerior separated the Vettones from the Carpetani. On the extreme south, the valley of the river Guadiana (ancient Anas) marks the approximate boundary between the Carpetani and Oretani. In terms of modern provinces, the area of our investigation would include all of Guadalajara, Madrid, Segovia, Soria and Valladolid; the southern part of Burgos and Palencia; the western part of Cuenca, Teruel and Zaragoza; the eastern part of Toledo and Zamora; the north-eastern part of Ciudad Real; and the southernmost tip of La Rioja (Figure 1.3). The total size of this study area is approximately 100,000 square kilometres.

Figure 1.2 Physical map of Central Spain. The broken line delineates the area of study.

This extensive plateau is often called the Meseta (‘great table’), a term coined by Alexander von Humboldt in 1799. Its surface consists largely of Tertiary deposits superimposed on a folded Hercynian base. The northern submeseta (Old Castile) averages 800 metres in altitude, the southern (New Castile) 600 metres. Each submeseta is drained by a major east–west river which begins in the Iberian Cordillera, the Duero (ancient Durius) in the north, and the Tajo (Tagus) in the south; both are navigable only by small river boats. Their numerous tributaries, often seasonal in flow, were aptly compared by the playwright Tirso de Molina with the colleges of Alcalá and Salamanca, since they have courses only in winter (Vázquez Fernández 1996: 349). The Central Cordillera divides the Duero and Tajo basins, while a lesser range, the harsh but fertile Montes de Toledo, forms the watershed between the Tajo and Guadiana. The terrain of the Meseta comprises two levels: the concave alluvial plains (campiñas) and, towering above them, the limestone-capped páramos (elevated plateaus) whose sides have been eroded by the action of wind into cuestas, steep slopes of marl. Much of the western Meseta is covered by dry, siallitic soils, which in some places take the form of sand, such as in the pine forests of north-western Segovia and at the base of the granitic Central Cordillera. The eastern Meseta consists predominantly of calcareous soils, which in one zone (comprising south-eastern Madrid, Guadalajara and Cuenca provinces) are mixed with gypsum. Also calcareous are the heavy yellow soils of the Tierra de Campos (central Duero), admirably suited to cereal culture. Areas of saline soil can be found in parts of the Duero basin and in the upper reaches of the Guadiana and Tajo (E.H. Villar 1937: 115, 197–8, 362).

Figure 1.3 Map of modern provinces in the area of study.

The continental climate of Central Spain is marked by extremes of temperature as well as dryness produced by the mountains that block rain-bearing clouds from both Mediterranean and Atlantic. The long, cold winter and brief, hot summer are neatly captured in two Castilian proverbs. One of these describes the region’s climate as ‘nine months of winter and three of hell’; the other quips that the cities of Castile have only two estaciones (seasons, stations): winter, and the train. In the northern Meseta temperatures can reach as high as 42°C in summer and as low as – 9° in winter. The cold – fifty days of frost annually at Palencia, and over ninety at Soria – is intensified by the winds howling out of the mountains. Average annual rainfall ranges from 356 millimetres at Zamora to over 1000 in the mountains (García Fernández 1986: 199–230). In the southern Meseta, extreme temperatures of 44° and –23° are recorded. In Roman times the cold winters of the Tajo valley were said to numb the bodies of bears roused from their caves (Claudian, Cons. Stil. 3.309–13). But in summer, a sirocco from the Sahara Desert may blow hot, dry air, and sometimes African sand, into Central Spain. In terms of precipitation, a ‘dry band’ stretching southeast from Toledo into the barrens of La Mancha (an Arabic name meaning ‘waterless’) receives less than 400 millimetres annually, whereas northern Guadalajara and eastern Cuenca can receive in excess of 700. The climate affects not only nature – perennial farm crops will not grow in the northern Meseta – but also human activity. In winter, the ancient Celtiberians wore a thick cloak (sagum) to protect against the cold, which in 153–152 BC was so severe that many Roman soldiers froze to death in their camp. Heavy spring rains in 181 BC prevented the Celtiberians from relieving the Roman siege of Contrebia (Livy, 40.33.2). In 134 BC the army of Scipio Aemilianus had to march at night because of the extreme heat, and some of its horses and mules died of thirst (Appian, Iberica 47, 88).

Central Spain has its own repertoire of flora and fauna. In antiquity much of the region, including areas now occupied by pine forest, was covered with stands of evergreen oak (Quercus ilex). However, it would be a mistake to think of the Meseta as a vast primeval forest like ancient Gaul: the parched climate and the Celtiberians’ preference for constructing buildings of stone and mud-brick rather than timber tell against such a condition. More likely there were dense patches of forest separated by open plains; Appian, describing the campaign of Lucullus in 151 BC, records a large expanse of wilderness between Cauca and Intercatia (Appian, Iberica 53). The extent to which these woods were depopulated in antiquity is uncertain: some trees must have been cleared for agriculture or for use as fuel, furniture or house beams. Denudation of forest would lead to soil erosion, and the ground surface would become hotter in summer and colder in winter without a forest canopy to shield it from sun and wind (Cronon 1983: 122). Though grain was grown here in pre-Roman times, grapes and olives were unknown until introduced by the Romans. Even today in the northern Meseta, cereals account for only 16 per cent of the land use, grapes and olives less than 1 per cent (Carbajo Vasco 1987: 167); this agricultural profile differs markedly from the Mediterranean model dominated by the triad of grain–grape–olive. This rugged land also supported a variety of wildlife. For the classical period we know both from literary sources and bone evidence that there were wild bears, boar, deer, wolves, foxes, hares, rabbits, beavers, mice, pigeons, partridges and pelicans, and such domesticated species as cattle, oxen, sheep, goats, pigs, horses, asses, mules, chickens, dogs, cats and even camels. Eagles with huge wingspans still impress visitors to lofty sites such as Termes today. River-fish include trout, barbel, surmullet and carp, as well as eel, crayfish and river molluscs.

But beneath the landscape that is visible today, there is a historical, cultural landscape that reflects human interaction with nature in past times. Archaeological information on settlements (chapter 4) and land use (chapter 5) complements literary and epigraphic testimony on social life (chapter 6) that helps us piece together what conditions were like in earlier times.

The idea of Romanization

‘Romanization’ is a descriptive rather than a definitional or explanatory term. It is a convenient name for a construct or paradigm devised by modern scholars to describe the process of cultural transformation by which indigenous peoples were integrated into the Roman empire. In recent years, however, both the concept of Romanization and the word itself have come under fire, because of its long-standing associations with an obsolete colonial and Romanocentric view of cultural change. Yet ‘old concepts can be redefined to serve radically different agendas: stripped of their “baggage”, they can take on a new lease on life … and still prove very useful to our debate’ (Keay and Terrenato 2001: ix). Thus, rather than abandoning the term ‘Romanization’, it is preferable to deconstruct and revitalize it as a useful descriptor of an important cultural process in the Roman world. In any event, the continuing popularity of the term, as exemplified by a recent spate of books with ‘Romanization’ in their titles (MacMullen 2000; Fentress 2000; Keay and Terrenato 2001; Arasa i Gil 2001; Pollini 2002), shows that it is not about to disappear. And as the latest assessment avers, students of Romanization are not flogging a dead horse: ‘The horse still breathes … and [is] well worth another crack of the whip’ (Merryweather and Prag 2002: 8, 10).

As a construct, ‘Romanization’ contains ambiguous or fallacious assumptions that until recently have not been examined. We therefore need to deconstruct it by exposing problems with the concept of Romanization and devising modifications to that concept to eliminate its inaccurate connotations. We then need to find a model of Romanization that will faithfully describe its operation. In what follows I shall first discuss the problems, and then examine the validity of several models that have been proposed.

One problem is the meaning of ‘Roman’. Early investigators naively understood this to mean the culture of Rome, but such an assumption is vulnerable on two counts. First, ‘Roman’ culture was not homogeneous, but multifaceted and unstable (Barrett 1997: 51). It underwent dramatic changes in the Late Republic and Early Empire, even as provincials were attempting to adjust to it. Moreover, no culture exists in isolation from others (Schortman and Urban 1998: 109); many facets of ‘Roman’ culture were in fact borrowed from Greek or other cultures. It is therefore unsound to reify ‘Roman culture’ as a fixed, recognizable entity. Indeed, some would argue that Rome had no real cultural identity until the ‘cultural revolution’ crafted by Augustan ideology around the turn of the millennium (Keay 1995: 323; Grahame 1998: 175; Woolf 2001). Second, evidence of Romanization is often adduced from finds of ‘Roman’ materials such as pottery or glass, whereas many of these objects were not made in Rome or even Italy but in the provin...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of figures

- Acknowledgements

- A note on place names

- List of abbreviations

- 1 Introduction

- 2 The indigenous culture

- 3 Conflict and reorganization

- 4 From hillfort to city

- 5 The changing countryside

- 6 Identity and status

- 7 Resource control and economic integration

- 8 Religious duality: dissonance or fusion?

- 9 Linguistic transformations

- 10 Life and death: the Romanization of behaviour

- Appendices

- Bibliography

- Index