eBook - ePub

A History of Greek-Owned Shipping

The Making of an International Tramp Fleet, 1830 to the Present Day

This is a test

- 480 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A History of Greek-Owned Shipping

The Making of an International Tramp Fleet, 1830 to the Present Day

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Greek-owned shipping has been at the top of the world fleet for the last twenty years. Winner of the 1997 Runciman Award, this richly sourced study traces the development of the Greek tramp fleet from the mid-nineteenth century to the present day. Gelina Harlaftis argues that the success of Greek-owned shipping in recent years has been a result not of a number of entrepreneurs using flags of convenience in the 1940s, but of networks and organisational structures which date back to the nineteenth century.

This study provides the most comprehensive history of development of modern Greek shipping ever published. It is illustrated with numerous maps and photographs, and includes extensive tables of primary data.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access A History of Greek-Owned Shipping by Gelina Harlaftis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Part I

THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

1

TRADE AND SHIPPING OF THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN AND THE BLACK SEA IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

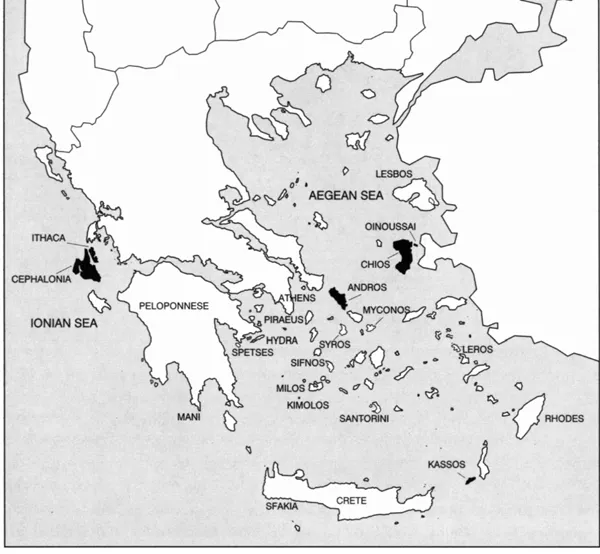

Three centuries after the fifteenth-century destruction of the Byzantine Empire, Greeks once again became important in the maritime and commercial affairs of the eastern Mediterranean. In the interim, the Genoese, Venetians and Raguzans in the sixteenth century, the Dutch and English in the seventeenth, and the French and English in the eighteenth controlled the trade and shipping of the Aegean, Ionian and Adriatic seas.1 In the ‘most hospitable sea of the globe’, the Aegean archipelago was part of the commercial and maritime empires of the Genoese and Venetians.2 Throughout the fifteenth century the Italians took advantage of the Ottomans’ naval weakness and concentration on the Balkans to establish themselves on strategic islands. Their commerce had an important impact on subsequent developments. The island of Chios, home of the most important eighteenth–,nineteenth–and twentieth-century Greek merchants and shipowners, was a Genoese colony for more than two centuries; even after it was conquered by the Turks in 1566 it was granted special privileges and a high degree of autonomy. The islands of Syros and Andros, as well as the other Cycladic islands that formed the core of nineteenth-century Greek shipping, were ruled by Venice for three centuries before coming under the Ottomans in the sixteenth century. Andros was conquered in 1566 and Syros in 1537.

Their large Greek Catholic populations combined with their seafaring traditions provided them with special privileges within the Ottoman Empire and protection from the western powers that lasted until the nineteenth century.3 The other area with a long maritime tradition was the Ionian islands, part of the Venetian maritime empire from the fourteenth to the late eighteenth century. The activities of Ionian merchants and shipowners who established themselves throughout the Black Sea in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries proved fundamental to the development of nineteenth-and twentieth-century Greek-owned shipping.

Extensive piracy by both Muslims and Christians plagued the Aegean from the fourteenth century and caused great suffering to Greeks. The Porte allowed and instigated Turkish pirates in order to extend its sphere of influence while Sicilian, Italian, Catalonian, Genoese and French pirates, along with the Order of the Knights of Saint John of Rhodes, raided ships, cargoes and local populations with the ultimate goal of blocking Turkish expansion.4

Figure 1.1 Main islands of origin of twentieth-century shipowners

Although Greek maritime activities from the fifteenth to the eighteenth centuries remain a topic that still needs investigation, there is enough evidence to show that the people of the Aegean archipelago and the Ionian sea manned, operated and built ships for all the nations that sailed their seas. The Greeks built their own small coastal craft and carried on trade between the numerous islands in the Aegean and Ionian seas. Islands that remained prosperous from the fourteenth to the eighteenth centuries, such as Chios, Crete and the Ionian islands, owned a significant number of ships which they used to carry cargoes to the large regional urban centre, Constantinople. Wars, pirates and lack of naval protection destroyed any attempts to establish a significant merchant marine. Instead, Greeks built ships for Venetians, manned the Ottoman imperial fleet and the ships of Barbary corsairs (the famous Barbary corsair and eventual Turkish admiral, Kayr al Din Barbarossa, was a renegade Greek from the island of Lesbos) or became small-scale pirates. The Greek pirates from Sfakia (southern Crete) or Mani (southern Peloponnese) were noted for their atrocities.5 Greek privateers appeared in the eighteenth century during the Russo– Turkish War when the Russians granted protection to the small-scale pirates from Sfakia, Mani and the Aegean islands of Spetses, Hydra and Psara. The poverty and the barrenness of most of these islands meant that piracy was a welcome part of a shadow economy that used illegal transactions ultimately to invest in legal enterprises, such as shipbuilding. Greek and western pirates had close relations and even protection from local merchants and Turkish officials and sold stolen cargoes cheaply. Some Cycladic islands, such as Milos, Kimolos and Myconos, owed their prosperity to special relations with the pirates.6

It seems that piracy and privateering were the first methods to accumulate substantial amounts of capital in the eighteenth century with which to engage in legal commercial and maritime activities. A striking example is Ioannis Varvakis, a privateer from Psara, who in the 1770s invested his profits in the first Psariot three-masted sailing ship. In 1774 Varvakis, who was wanted by the Ottomans, emigrated to Russia, where he managed to obtain fishing concessions in the Caspian Sea from his base in Astrahan. When Varvakis moved to Taganrog in 1815 he was extremely rich, perhaps the first successful Greek merchant in southern Russia.7

This chapter analyses the nineteenth-century commercial and maritime activities in the eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea and specifies the Greek role. The chapter is divided into three sections. The first deals briefly with developments in the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century international environment that determined the nature of maritime commerce in the area; it further traces the movement of Greeks into Mediterranean ports. The second section looks at the main trade routes and cargoes hauled from the eastern Mediterranean and Black Sea. Finally, the last section examines the ships that carried this trade. Greek participation is traced at both the ports of origin and also the ports of destination; the arrival of goods and ships from all Black Sea and eastern Mediterranean ports in the two main recipient areas of western Europe, Marseilles and the British ports, is studied at the beginning of every decade.

THE INTERNATIONAL SCENE AND THE DIASPORA OF THE GREEKS IN THE MAIN MEDITERRANEAN PORTS

By the end of the seventeenth century it was evident that not only the Venetians but also the Turks were declining in the eastern Mediterranean. The eighteenth century saw competition among the European powers for a share of the Ottoman Empire: the Habsburgs and Russians advanced by land and the English and French by sea. The eastward expansion was to be to a great advantage to the Greeks. The second half of the eighteenth century witnessed tremendous economic

growth in western Europe.8 England and France competed for colonial and commercial hegemony around the globe, but especially in Europe. It has been estimated, for example, that in about 1800 40 per cent of British exports of finished manufactures and 84 per cent of British exports of all other goods were directed to Europe; at the same time, 70 per cent of Frances foreign commerce took place with other Europeans. While English trade surpassed the French in the northern Europe, France was predominant in central Europe and the eastern Mediterranean.9

Although Europe had been trading with the Ottoman Empire since the sixteenth century, it was really in the eighteenth century that a commercial surge occurred. Trade between Europe and the Ottoman Empire increased by both overland routes and the sea. The first commercial agreements were made with France and contained many provisions that were advantageous to Europeans. Most important were regulations concerning extra-territoriality that gave foreign consuls jurisdiction over their citizens.10 None the less, European merchants allowed to trade with the Ottomans faced great obstacles. Added to the Turks’ great hostility to foreigners was the Europeans’ complete lack of knowledge of the Ottoman language, customs and methods of trading. The Greeks proved to be just the intermediaries required. Towards the end of the eighteenth century, however, the middle men became independent merchants and shipowners with their own entrepreneurial networks.

Among the Christian populations in the Ottoman Empire, Greeks played the most important roles in government and trade by the eighteenth century. Greek became the language of commerce in the Balkans to such an extent that the term ‘Greco’ (or ‘Görög’ in Hungarian) came to mean ‘merchant’ in several languages.11 The leading role of the Greeks in handling Ottoman external commerce characterises the second half of the century. The conquests of Ottoman lands by the Habsburg and Russian empires were followed by policies that ultimately favoured Greek merchants. Both countries needed to expand their commercial and maritime activities; having no subjects willing or able to carry out such activities, they adopted preferential policies to attract foreigners. Political, economic and religious freedom were guaranteed to newcomers at Trieste at the beginning of the eighteenth century, while the treaty of Passarowitz (1718) secured a century’ peace in south-eastern Europe, during which trade and navigation thrived. Special concessions were provided to Greek immigrants, who were the best-known merchants of the Levant.12 The Greek community in Trieste ensured Austrian prosperity, as well as close economic relations with Smyrna, Constantinople and Alexandria through trade and shipping.

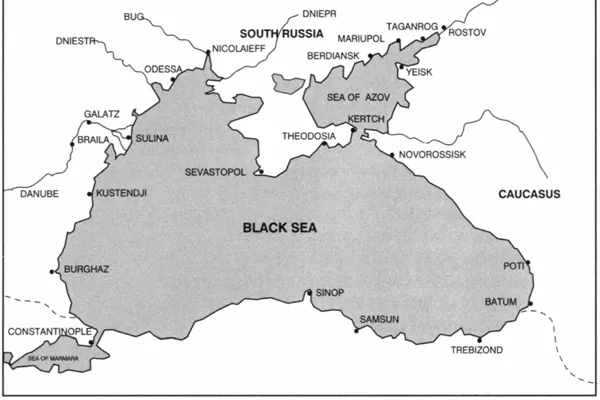

Much more massive was Greek immigration to southern Russia. Until the eighteenth century the Ottomans viewed the Black Sea as a mare nostrum and restricted navigation to Turkish subjects. The scene changed completely after the Russian victory in the Russo-Turkish War of the 1770s. The treaty of Kutchuk- Kainardji (1774), its Explanatory Convention (1779), and the Treaty of Commerce (1783) not only established Russian dominance on the northern coast of the Black Sea but also secured a long-desired direct sea route to southern and western Europe. Another fifty years were needed, however, to secure the right of free navigation for ships of all nations. The Russo-Turkish War of 1828–9 ended with another Russian victory, codified in the Treaty of Adrianople which provided Russia with absolute freedom of trade in the Ottoman dominions and guaranteed all peaceful nations complete freedom of navigation. This virtually internationalised the Straits and Black Sea, although the treaty made no such explicit statement.

When the Russians pushed into the Black Sea there was virtually no commerce in the area. Since the vast new area was almost totally unpopulated and the fertile soil uncultivated, the first concern of the Russian government was to stimulate population growth by attracting immigrants using land, agricultural equipment, and even building materials as inducements. In addition to encouraging native Russians to move to the new territories, new settlers were attracted from the Aegean archipelago and other parts of the Ottoman Empire. The encouragement of Greek settlements in southern Russia coincided with the establishment of a Russian protectorate over the Ionian islands. As a result, a great number of Greeks migrated to southern Russia from the Aegean and Ionian islands. The Greek revolt in the 1770s (which was supported by the Russians); the eventual Russo-Turkish war; the Greek war of independence (1821–9); and the second Russo-Turkish War of the nineteenth century (1877–8) stimulated continuous waves of Greek immigrants, not only to southern Russia but also to that part of Rumania under Russian protection. The economic prosperity of the Black Sea ports encouraged immigration that lasted until the end of the century. The incentives to live there were so great that the population of ‘New Russia’ increased from 163,000 in 1782 to 3.4 million in 1856.13

The Greek population in Russia before 1914 was estimated at about 600,000, of which 115,000 lived along the northern Black Sea coast from Odessa to Theodosia; 160,000 on the shores of the Sea of Azov; and 270,000 along the eastern coast of the Black Sea from Novorossisk to Batum.14 The Greek element was also very important on the south-east shores of the Black Sea, which continued to belong to the Ottomans. Throughout the nineteenth century a large number of Greek immigrants to Russia came from this area. In 1872, the entire population of the province of Trebizond was reported to be 938,000, one-seventh of whom were Greek.15 The south-western shores of the Black Sea, which until the 1870s formed an integral part of the Ottoman Empire, were characterised by a constant population movement which has made it impossible to calculate the exact number of residents in the numerous Greek communities. The pro-Russian Christian population of this area was the first to experience Ottoman retribution after the Russo-Turkish Wars of 1828–9 and 1877–8. The Greeks along the coast from the Bosporus to Kustendjie (Constanza), in contrast to those from the southern shores who engaged more in landborne commerce, were known for their seafaring and carried a large part of the Black Sea coasting trade.

Figure 1.2 The main Black Sea ports

If the Austrians and Russians promoted colonisation policies to attract a large number of Greek merchants and seafarers to their new lands, the British promoted their penetration by supporting Ionian and Greek merchants. The principal wheat suppliers to Britain prior to the Crimean War had been Russia and Prussia. Seeking alternative supplies, the British pursued closer ties with the Ottomans and tried to stimulate grain production in the Danubian Principalities.16 Between 80 and 90 per cent of the Greeks who engaged in commercial activities on the ...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- TABLES

- FIGURES

- PLATES

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- PART I: THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

- PART II: THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

- APPENDICES

- NOTES

- SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY