- 308 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Mixed use development is about retaining or creating a mix of different uses in cities or neighbourhoods. The trend in UK development has been towards specialisation and areas with single uses. Increasing the mix of uses is thought to reduce the need to travel, lower the likelihood of crime, improve the ambience and attractiveness of areas and contribute to the sustainability of cities.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

ArchitectureSubtopic

Urban Planning & LandscapingChapter 1

An Introduction to Mixed Use Development

Reclaiming The City is a book about mixed use development, and is mostly concerned with property development in cities. Mixed use development is a term that might at first sight seem obvious, but that is sometimes used in ways which are more confusing than helpful. Increasingly, mixing different land uses in the same geographical area is seen as a positive contribution to planning policy. It is hoped that by increasing the mix of land uses, and especially residential uses, residents will lead more ‘sustainable’ lifestyles, using their cars less. In addition, town and cities will become more attractive, viable and safer to live and work in. In effect, government policy is encouraging greater urbanization, and higher density cities.

The book examines some of the evidence to see whether this reoccupation of cities will have the desired effect. It introduces some new evidence that suggests that mixed use development may make a difference, and examines some of the wider factors that may nevertheless limit mixed use developments and so fail to deliver the significant changes that may be necessary to create more sustainable cities. This introductory chapter examines the background to the discussion about mixed use development and sets out the main points contained in the chapters that follow.

The Mixed Use Jigsaw Puzzle

As we have already stated, this book is concerned with the mixing of different uses, including residential uses, in city centres. Mixed use development has become increasingly important in recent years. There are a number of reasons for this, some of them interrelated. Each explanation for the interest in creating more mixed use development is like a piece in a jigsaw puzzle. This book attempts to describe each of the pieces, and show how they fit together to create a complete picture of the mixed use debate.

In recent years development pressures have continued to concern politicians and the wider public. Although the population of the UK is hardly growing, for various reasons the number of households continues to increase, creating a need for housing in addition to the necessity to replace worn-out buildings. Concerns about sustainability and the need to reduce car use – or at least to stop it increasing – have led to calls to stop the expansion of urban areas. Development pressures on rural landscapes or areas of particular scientific importance have become increasingly contentious. These pressures have led to new proposals to increase urban densities and create new ways of getting more people living in existing centres. This debate has tended to focus on the concept of the ‘compact city’. There are sharp disagreements between commentators about the value of this idea to UK planning practice, and Michael Breheny (Jenks et al., 1996) has questioned the relevance of the debate at all, given the degree of continuing urban decentralization. There are further heated debates about the nature of the evidence on the value of higher density cities.

At the same time the shake-out in employment, which once decimated manufacturing industry, has started to affect service employment. The introduction and use of new technologies requires new types of office building, and perhaps in the future less space (with fewer staff). New technologies also allow businesses to relocate anywhere in the UK or even beyond. London Electricity, for example, are establishing their customer services department in Sunderl and. The Prudential are establishing a new telephone-based bank, which will be located in Dudley in the West Midlands. In most cities older, ‘secondary’ office space is no longer needed; and may never be needed again. Other uses have to be found, as the economics of redevelopment (and the lack of demand for the space that would be created if redevelopment were to occur) means

Figure 1.1

60 Sloane Avenue, London. Conversion of the former Harrods depository into a mix of offices and retail uses in a predominantly residential part of Kensington.

that demolition is not a serious option. So throughout London, and in cities across the UK, former office buildings are considered for conversion to apartments, hotels or student halls of residence. And former industrial premises, and those once used for services supporting relocated industries, are also re-used in imaginative ways.

A further piece in the mixed use puzzle is the wish to sutain and improve town and city centres. Partly driven by the concern about increasing car use, government has acted to prevent many new proposals for out-of-town shopping (rather too late, in the view of some commentators). Instead, efforts are being concentrated on improving the vitality and viability of town and city centres. Similarly there are concerns about the quality of the places that are being created: the liveliness; the level of activity throughout the day; the design of individual buildings and the urban design context in which they exist. Mixed uses offer an opportunity to change aspects of this liveliness and design. A linked worry is about safety and crime levels; again, by mixing uses and having greater activity and therefore observation within an area it is thought that crime – or the likelihood of certain crimes taking place – can be limited.

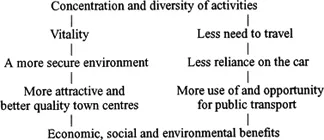

The government has recently explained the basis on which they increasingly support mixed use development in planning policy statements. This is illustrated by the diagram below (DoE, 1995a):

The Secretary of State for the Environment, John Gummer, has outlined this approach in a number of speeches. It has developed throughout 1995, and is reflected in the changing Government policy statements. One of the more detailed explanations was made at a conference in Manchester in July 1995 (DoE, 1995b):

The emerging consensus is that development is more sustainable if it produces a mixture of uses. Segregation of land uses, encouraged in the past, is not relevant now. The trend back to mixed usage brings a number of potential benefits. It ensures vitality through activity and diversity. It makes areas safer. It also reduces the need to travel, making people less reliant on cars, bringing welcome environmental benefits.Diversity of uses adds to the vitality and interest of town centres. Different, but complementary uses, during the day and in the evening, can reinforce each other, making town centres more attractive to residents, businesses, shoppers and visitors. That is why my draft revised PPG6 promotes mixed use development.Mixed use development should increasingly become the norm rather than the exception. It will be a gradual process of raising awareness amongst developers and investors of the benefits which can be realised.We will be expecting developers to think imaginatively in future as to how proposals can incorporate mixed land uses, to produce lively and successful developments over both the short and long term, and provide a positive contribution to the quality of our towns and cities.

This book examines many of these claims. While the overall views put forward by the Secretary of State seem persuasive, there are indications that some parts of the argument may be based more on hope than reality. The discussions about the topic can be summarized in the diagram below.

Why Mixed Uses?

| ADVANTAGES | DISADVANTAGES |

| Definite | Definite |

| Attractiveness and vitality – diversity; up to 24 hour city | Harder to dispose of property asset quickly |

| Uses unwanted or obsolete property, including listed buildings | Requires active management of property |

| Range of uses means greater likelihood of some parts letting | Therefore harder to raise finance and may put some possible tenants off |

| Possible | Possible |

| Reduction in travel (shorter trips, more multi-function) so reduced emissions; | Lower rents achieved |

| Problems of separate | |

| sustainability | access needed for each use |

| Reduction in crime; more activity; greater uses; observation of street | Conflict between activities; noise, traffic etc (e.g. housing over wine bar) |

While some of the advantages of mixed use can be accepted as absolute, others may or may not be true in certain circumstances. And there are undoubtedly certain perceived disadvantages of mixed use development that are overlooked by the government’s statements, and which may well be the deciding factors in the decisions taken by development companies or investors. Some of these are illustrated in the case studies and examples that are included in the following chapters.

Clearly there are very good reasons that can be advanced for the development of mixed use schemes and areas, and these are examined in the book. It is also worth noting that there are distinct advantages for the government in adopting this approach as the basis for policy. The policy has no financial consequences for the government; no additional public expenditure is needed. However, the property industry may well incur greater development costs in building mixed use schemes.

In addition, by attacking obsolete local authority zoning (which is almost non-existent, and reflects an approach abandoned by local authorities since the late 1960s) there is a perception of pushing down barriers that many in the property market believe still to exist. ‘Planner bashing’ has been a favoured approach to excuse failures of the market for many years: for example, Michael Heseltine made a statement in 1979 about jobs being locked away in planners’ filing cabinets to justify speeding up the development control system. This might be seen as merely a development of that approach (Thornley, 1991).

Definitions: Mixed Use and Mixing Uses

The terms ‘mixed use’ or ‘mixed use development’ are widely used, but seldom defined. Without definition, considerable confusion can be generated, mainly because the issue of scale can be crucial. Recent debates over planning policies designed to create a greater mix of uses show why this can be important.

Some planning authorities have adopted policies that have a size threshold; schemes over (for example) 300 m2 must include a mix of uses. Others have been less prescriptive, concentrating on encouraging a mix of uses within an area. For the potential developer these differences of definition can be crucial; do they have to provide a couple of retail units on the ground floor of an office building? Would a development of flats on an adjacent site next to an office development meet the planners’ requirements?

These are therefore more than merely academic questions, and it is possible to illustrate the range of ways that ‘mixed use development’ can be interpreted. In some parts of the USA for example, mixed use implies a mix of commercial and residential. Offices over shops would not fit the bill; they are both commercial uses.

Again, in the USA, the Urban Land Institute takes an even harder line; mixed use developments (MXDs) must have three or more significant revenue-producing uses, with significant physical and functional integration (including uninterrupted pedestrian connections), and be developed in conformance with a coherent plan. Everything else that has a mix of uses is downgraded to a ‘multiuse project’ (Urban Land Institute, 1987). Yet even with this apparently limiting definition, hundreds of large-scale planned mixed use development projects exist in city centres across North America.

Confusions can arise over the use of the term ‘mixed development’. In the context of housing, the term ‘mixed development’ often turns out to refer to a mix of houses and flats. In another housing context the same term is used to refer to a mix of private for sale and rented accommodation. In other contexts it has been used in relation to a mix of public and private development. None of these necessarily involves any mix of uses.

Confusion also clearly exists in the minds of some chartered surveyors. A recent journal article on mixed use development included a photograph of Milton Keynes, captioned ‘Milton Keynes demonstrates the advantages of well-planned mixed-use dev...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- Chapter 1 An Introduction to Mixed Use Development

- Chapter 2 A History of Mixed Uses

- Chapter 3 Mixed Use Development as an Agent of Sustainability

- Chapter 4 Cities, Tourism and Mixed Uses

- Chapter 5 Mixed Use Development and the Property Market

- Chapter 6 Mixed Uses and Urban Design

- Chapter 7 Crime and Mixed use Development

- Chapter 8 Local Policy and Mixed Uses

- Chapter 9 Why Developers Build Mixed Use Schemes

- Chapter 10 Mixed Use and Exclusion in the International City

- Chapter 11 Mixed Use Development: Some Conclusions

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Reclaiming the City by Andy Coupland in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Urban Planning & Landscaping. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.