This is a test

- 544 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Collected Writings of Gordon Daniels

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Originally a student of Meiji Japan, Gordon Daniels is widely known for his work on the Pacific War and the Occupation of Japan, with particular regard to the world of communications in film and propaganda as well as Japanese sport. He has also been closely involved with the post-war era of international relations and Japan, as well as studies in Japanese history and historiography. In the 1980s he made significant contributions in reporting on the scope and development of Japanese Studies in Britain. His most recent work has been as joint editor (and contributor) with Chushichi Tsuzuki of Social and Cultural Perspectives - the fifth of the five-volume series on the history of Anglo-Japanese Relations (Palgrave, 2002).

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Collected Writings of Gordon Daniels by Gordon Daniels in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Bakumatsu and Meiji: Anglo-Japanese Relations and Westerners in Japan

First published in Modern Asian Studies, II, 4 (1968), pp. 291–313

1

The Japanese Civil War (1868)—A British View

IN THE LATE AUTUMN of 1868 political events in Japan were no longer focused exclusively on Edo, saka and the lands of the south-western han; all of which could be easily visited by British sailors and diplomats. The Imperial armies had won important victories at Fushimi and Ueno but they had still not gained control of the whole of Japan. The last Sh gun had retired from the conflict but his supporters still mounted stubborn military resistance in Northern Honsh .2 At this stage it was important for Britain to know the state of this civil war and its likely outcome.

At the beginning of this struggle in January 1868 Sir Harry Parkes, the British Minister in Japan, feared the probable consequences of the Western powers becoming involved. He had grimly noted the recent attempts of the French Minister, Léon Roches, to monopolize the affections of the Tokugawa,3 and, should there be competitive intervention in the emerging war, fighting might well be protracted. In such a situation Japan might well fall victim to predatory powers. Also on a popular level; should Western states openly associate themselves with the conflicting parties, in future it might well be impossible for them to be broadly accepted in Japan. To deal on the basis of Western unity obviously promised a more stable future than to deal on a basis of each power to its own client. If the civil war was drawn out British businessmen would suffer;4 instability might produce a return to anti-foreign terrorism.5

To prevent any such unsavoury developments, Parkes persuaded the American and European diplomats to issue a declaration of neutrality and non-intervention in February 1868.6 And despite his sympathy for the Emperor, which grew as the new government showed itself friendly and reliable,7 the British Minister maintained a stance of non-involvement. Even so, from the point of view of both Parkes and the new regime the sooner relations could be normalized the better.

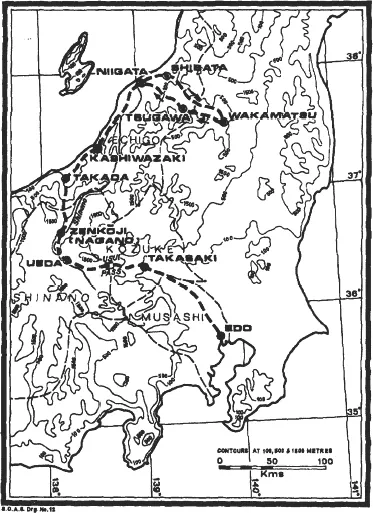

In October 1868, with the Imperial armies still marching northward, it was difficult for Parkes or any other European to have a clear impression of the political and military situation. Several factors made foreigners’ knowledge inadequate and confused. The battlefields were far distant, some two hundred miles away, to the west of Japan's difficult central mountain chain. The links across the country were fragile; tracks and roads which were amongst the worst in the world, and news was carried on foot by Japanese runners. Besides this it was likely that the new government would conceal any news of reverses for fear of losing face among foreigners. Any information, therefore, that came from the scene of conflict would be hard to assess, particularly as foreigners had never visited the area and did not know the simple facts of its geography.

At this stage it is worth recalling that Victorian self-interest was not without some constraints of morality, and some British activities in Japan in the closing months of 1868 provide a fine example of self-interest, the profit motive, and humanitarianism inextricably interwoven. On 2 October Higashizuke Michitomi wrote to Sir Harry Parkes asking if he would release William Willis, a legation doctor and Vice-Consul, to travel to the West coast, to give medical treatment to wounded members of the Imperial army.8 The new regime had probably been convinced of the superiority of European medicine by the successful treatment Willis had given to wounded Satsuma troops at Ky to at the outset of the civil war.9 Parkes had taken the opportunity to send as well Ernest Satow,10 his chief scholar of Japanese, to sound out opinion and to speed up negotiations on the punishment of Bizen officers who had recently ordered an attack on Europeans at Hy go (K be).

Parkes now agreed to send Willis on the condition that he should treat the wounded ‘regardless of...party’,11 that is, he should treat both Northern prisoners and the Emperor's men. This condition can probably be ascribed to three motives: a desire to keep up an appearance of non-involvement, pure humanitarian sentiment, and a desire to gain popularity for foreigners among Japanese by helping as many men as possible. Certainly, from the wide scope of Willis’ reports on his journey, it is clear that it was not purely an errand of mercy; though his restless exertions in difficult conditions show that he took the humanitarian side of his mission very seriously. In Willis, as in Parkes, there were genuine humanitarian sentiments, but this mission would provide a perfect opportunity to see at close hand what the situation was over large tracts of previously unknown territory, and in the more immediate combat area. Furthermore, there might be opportunities to see the economic potential of these unknown areas and to persuade the Japanese of Parkes’ basic philosophy. This was that if the Japanese saw Western medicine, inventions, commerce and transport at work they would be easily persuaded of their superiority, and realise that to take over the good things of Europe would lead to a stabler, richer and happier society.12 Such a society would, of course, offer extensive markets for British goods, be a safer place for foreign residents, and stimulate the production of silk, the commodity which British merchants found highly profitable.

On 5 October 1868 William Willis, with his Japanese teacher, two Japanese doctors, his cook and a guard of twenty-five men from the Ky sh fief of Chikuzen, left Edo for the west.13 He rode in a litter which was carried by local coolies. Their route lay over three distinct areas—the rich Edo plain, the central mountains, and the narrow coastal lowland on the shore of the Sea of Japan. This crossing was slow and arduous. Winter was approaching and rains were so heavy that the roads had become a morass while the rice, wheat, bean and cotton crops had been ruined. Rivers were overflowing and flooding was widespread. Willis wrote of his route:

I...observe the great want in Japan of a real central government. There are no public works of any importance, in places close to Edo the roads were the worst I had ever seen. The mud was knee deep and with the utmost effort it was in places impossible to get over twenty miles a day. There were no bridges of any importance spanning rivers, all traffic...depending upon ferries of the most primitive character.14

Still, if the physical discomforts of travel were endless the population and his escort were friendly. Village officials welcomed him in ceremonial dress, provincial check points were thrown open and he was warmly received at inns previously the sole preserve of travelling daimy and their followers.

However, the bulk of Willis’ report on his journey to Takada through lands free from any sign of war damage was devoted to popular feeling and the impact of foreign trade. From the standpoint of the British who longed for stable government and flourishing trade there was much that gave cause for optimism. No one Willis and his Japanese teacher interviewed seemed cold or hostile towards the new government, though reactions differed according to social class. The innkeepers and shopkeepers, though looking back nostalgically to the ‘good old days’ when the daimy and their spectacular cavalcades spent money freely on their way to Edo, voiced no sympathy for the old government. In the silk producing areas of the Edo plain it was said ‘the money that changes hands is so considerable that innkeepers speak of it as...compensating for the old traffic’.15 Among the farming community, too, opinion, though varied, was generally sympathetic towards the new rulers. The tenants of the large landowners seemed somewhat indifferent to recent changes but those who had rented fields from the Tokugawa hatamoto were very favourably inclined to the new rulers. For them conditions had been so severe under the Shogunate that things could hardly have been worse, so any change was probably a cause for optimism. After the oppression and injustice of their old landlords the new government was thought likely above all to secure ‘more uniformity and justice in the amount of tribute assessed on government land’.16 It appeared that even though many of these tenant farmers had not been actively bearing arms for the Imperial army there were at least strong passive supporters of its cause. Good reports were also received of the state of affairs further west. In fact, by all accounts, the Tokugawa backwoodsmen were merely fighting for terms.

From Willis’ observation there seemed to be an economic, social and climatic dividing line across Japan which was marked by the Usui Pass. To the east of it silk producers looked to Yokohama as the best outlet for their goods, to the west silk farmers looked forward to the opening of Niigata when they would be able to send their crop by boat down the River Shinano to be marketed. This seemed to promise well for future foreign merchants at that port. The western highlands, Willis recorded, were a good 10°F colder than the Edo plain but the population of the chillier west seemed handsomer than that of the lowlands, of which he wrote: ‘The women are ugly and the men...weak and stupid looking’.17 As this indicated, Willis did not look upon the Japanese with the sweet and sour romanticism of many European writers. He found most villages ‘more repetitious of each other’, with a ‘stench...offensive to a degree’.18 As a Victorian brought up on the virtues of cleanliness, he was depressed by the Japanese ‘great indifference as regards air and water’ to which with their ‘comfortless houses and poor diet’ he ascribed the ‘sickly looks’ of many people.19 In the rich lowland province of Musashi the change of regime seemed to have produced an outbreak of lawlessness and a breakdown in the police system. Now an attempt was being made to restore order through meting out heavy sentences.

Still, the future of the all-important staple, silk, seemed highly promising. In the Edo plain the areas under silk had doubled in a few years, while in the last decade the price ‘had risen five and six fold’.20 ‘The silk farmers seem to have good times of it’21 wrote Willis, and in their areas many substantial houses were to be seen. Unfortunately for the merchants at Yokohama who made contracts in advance, prices at the source of supply were now higher than the prices at which they had promised to sell. This apart, the silk trade seemed to have a rich future ahead, a future which Willis thought could be even more golden if more land were devoted to mulberries and less to rice. In this he seems to have been thinking more of the profits of his countrymen than of the food needs of the Japanese.

If the export trade looked healthy, there was also evidence of a wider distribution of imports. For in many towns and villages along his route foreign textiles could be seen on sale. This and the fact that ‘all but the most primitive’ household utensils in dwellings along the road came from Edo or Ky to seem to show there was a considerable amount of internal trade in objects that were not bulky; coolies and animals could hardly have taken larger loads.

On the arduous twelve-day journey to Takada, Willis’ party were so slowed by weather and terrain that they could cover only some twelve miles each day. Fortunately only three towns of any size lay on their route— Takasaki, Ueda and Zenk ji (Nagano), and none of these held much to delay the travellers. It was also a compensation that Willis’ escort were so co-operative. The officers of the old Tokugawa administration had usually been evasive and obstructive but the present guards gave him every aid in pressing his enquiries. For he wrote: ‘All who accompanied me obtained for me any information that I required’.22 He was on occasion embarrassed at not being able to pursue his investigations alone, for the presence of soldiers may well have cowed some people into silence. But this drawback was certainly outweighed by the tact and industry of the doctor's Japanese teacher. Without him, as Willis admitted, ‘it would have been impossible or impolite to make certain enquiries that only a native could make quietly and with considerable circumspection’.23 And to him Willis was ‘much indebted’ for what he learned on the way.

On 17 October Willis and his companions arrived at Takada, which he remembered as one ‘interminable street’ with vast overhanging roofs to keep off the winter snows.24 Here, close to the sea, the serious part of the doctor's work began; in screened-off sections of Buddhist temples were four...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction: Japan, Japanese History and Japanese Studies, 1941–2000

- PART I: BAKUMATSU AND MEIJI: ANGLO-JAPANESE RELATIONS AND WESTERNERS IN JAPAN

- PART II: JAPAN IN THE PACIFIC WAR: SOCIETY, CULTURE, BOMBING AND THE UNITED STATES STRATEGIC BOMBING SURVEY

- PART III: THE ALLIED OCCUPATION, 1945–52, REFORM, INTERNATIONAL RIVALRIES AND BRITISH POLICIES

- PART IV: JAPANESE HISTORY, HISTORIOGRAPHY AND HISTORIANS

- PART V: POSTWAR JAPANESE FOREIGN RELATIONS AND EURO-JAPANESE RELATIONS

- PART VI: CINEMA, SPORT AND THE MASS MEDIA

- PART VII: JAPANESE STUDIES, JAPANESE LANGUAGE TEACHING AND INTERNATIONAL ACADEMIC COOPERATION

- EPILOGUE

- Bibliography

- Film Index

- Index