This is a test

- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Drawing on case studies and presenting archaeological evidence throughout, Alan Greaves presents a welcome survey of the origins and development of Miletos.

Focusing on the archaic era and exploring a wide range of issues including physical environment, colonizations, the economy, and its role as a centre of philosophy and learning, Greaves examines Miletos from prehistory to its medieval decline.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Miletos by Alan M. Greaves in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

1

MILESIA

The territory, physical environment and natural resources of Miletos

An understanding of the physical environment is not just useful but essential when one is trying to understand any ancient city. This chapter provides a description of the physical environment of the land around Miletos, its geology, soils, water, natural resources, communications and agriculture which will be the basis for the later chapters that discuss the city’s historical development. Research into the khora (territory) of Miletos is currently being carried out (see interim reports by Lohmann, listed in the bibliography) but what is presented here is a purely casual and personal understanding of the area from one who has visited it, but not systematically studied it. My objective has been to create a backdrop to understanding the themes of this book, not to create a definitive landscape history.

It is impossible to say anything about the amount of territory controlled by the settlement of Miletos in the prehistoric period. Although evidence has been found for a large Minoan presence at the site, Minoan material does not appear to have penetrated very far inland. In the Mycenaean period, pottery is found in the interior, including Didyma, but the extent of Miletos (Millawanda)’s territory cannot be ascertained, although the northern plain on which Miletos stands would form a single, geographically distinct, zone which could be assumed to have been controlled by the settlement.

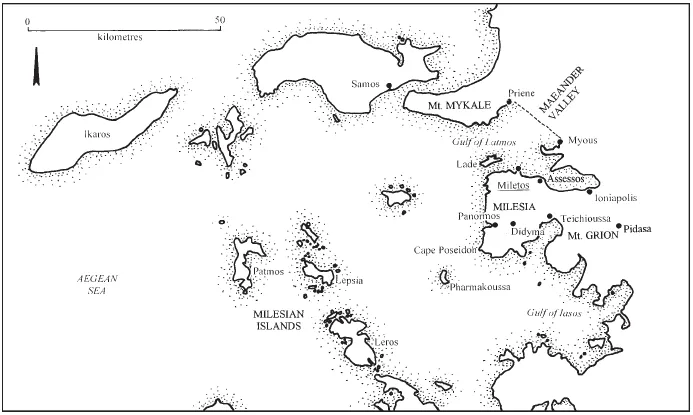

From the Archaic period, we have better evidence about the extent of the Milesian territory. The name Milesia is known to us from Herodotus (1.17, 18, 46, 157; 5.29, 6.9) and Thucydides (8.26.3) who use it to describe the khora of Miletos. The exact size of that territory cannot be determined with any certainty as we do not know its precise limits and its area appears to have changed over time. The core area of the Milesian territory, that part which is called Milesia in the texts, included the whole of the limestone peninsula on which the city was positioned on the northern side as far east as the settlement of Teichioussa on the modern Bay of Akbuk (Lohmann, 1997, 290; Rubinstein and Greaves forthcoming, see Figure 1.1). This is an area of approximately 400 square kilometres and research is continuing to try and ascertain the true extent of Milesian territory (Lohmann, speaking in Ankara, 29.05.01) and the results of that work are eagerly awaited. In addition to this core territory, Miletos probably possessed part of the Maeander valley, the Mykale peninsula and Mount Grion and also some of the surrounding islands (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 The territory of Miletos.

When Miletos defeated Magnesia-on-the-Maeander (Hdt. 1.18) it can be assumed that they took possession of some of the Maeander valley that must previously have belonged to Magnesia. Although the site of Archaic Magnesia is not yet certain, research has been carried out in the area close to the later settlement of Magnesia in order to try and locate the Archaic settlement (Orhan Bingöl, speaking in Güzelçamlı, 29.9.99). If one calculates the extent of the valley from the site of classical (and presumably nearby, Archaic) Magnesia to where the mouth of the Maeander is estimated to have been in c. 500 BC (Aksu et al. 1987b: 230, see Figure 1.5), it is approximately 320 square kilometres.

Mount Grion, the area of uplands to the east of Milesia (modern Ilbir Dağı), appears also to have been largely controlled by Miletos in the Archaic period. When the Persians conquered Miletos and divided its territory up, they gave this area of uplands to the Karians and the town of Pidasa (modern Cert Osman Kale) was settled and occupied until c.180 BC (Hdt. 6.20; Milet 1.3: 350–7, no. 149; Cook, R.M. 1961: 91–6; Radt, 1973–4). The location of this site, high in the mountains and quite far inland, away from Miletos, is an indication of the size of this area possessed by Miletos in the Archaic period. This mountainous area must have been a considerable addition to Milesian territory, covering perhaps 300 square kilometres. Miletos also had a cult site on the opposite shore of the Gulf of Latmos, at Thebai on the Mykale peninsula (Ehrhardt 1988: 14–15), although the amount of territory associated with this cannot be determined.

Several of the many small islands to the west of Miletos were also under the city’s control during certain periods of its history. Although it is easier to measure the size of islands when compared to estimating the size of Miletos’ land-based territories, it is harder to know when they were under Milesian control, due to a general lack of source materials. The smallest and closest of these islands was Lade (modern Batıköy, formerly Kocamahya Adası; c. 2.5 square kilometres). There are no archaeological remains on Lade but it had great strategic importance as it protected the western harbours of Miletos from storms and attack from the open sea (Greaves 2000a: 40–6). Lepsia (modern Lipsoi; c. 14 square kilometres) may also have been under Milesian control at some point in time, although exactly when is not clear (Ehrhardt 1988: 16–17).

Leros (modern Lero; c. 64 square kilometres) must have come under Milesian control during the Archaic period (Strabo 14.1.6, citing Anaximenes of Lampsacus; Hdt. 5.125) and remained under Milesian influence in the Classical and Hellenistic periods (Paton 1894; Milet 2.2: 26; Ehrhardt 1988: 16). Leros was used as a stop in this way by the Peloponnesian and Sicilian fleet, according to Thucydides (8.26), and provided Miletos with useful anchorage. Patmos (c. 40 square kilometres) is known to have been a deme (district) of Miletos in the Hellenistic period (SIG3 1086), but its only mention prior to this (Thucydides 3.33) makes no mention of which state controlled the island. The island’s hourglass shape provides sheltered harbours on both the eastern and western sides, although the eastern bay is the focus of the modern settlement.

Ikaros (modern Nikaria) is a large island (c. 340 square kilometres) and was probably under Milesian control in the Archaic period when it was useful to Miletos for its harbourage (Strabo 14.1.6, citing Anaximenes of Lampsacus; Dunham 1915: 48 and note 1; Ehrhardt 1988: 18–19). Ikaros became independent in the fifth and fourth centuries BC and then came under Samian control. Although the island supported two poleis in the fifth century BC, it is not very fertile and it is mostly suitable only for sheep and goat herding. The territory of Miletos changed over time, but at its fullest extent it was considerable. Much of this area may appear barren, especially the islands and mountains, but it provided ample grazing for flocks, which were an important part of the city’s agriculture and economy, and supplied the city with timber (see below, see page). Two parts of the Milesian territory, however, were agriculturally rich – the northern plain and the Maeander Valley – and Miletos’ control over these were to be vital for her economy and ability to support her population.

Geology

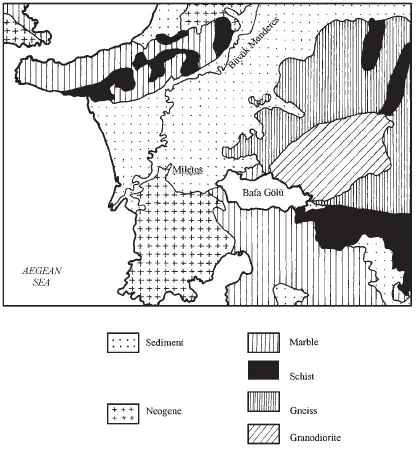

The geology of the region around Miletos is complex with a wide variety of different rock types and formations (see Milet 3.5; Brinkmann 1971; Gödecken 1984, 1988: esp. 308–9; and M.T.A. 1989). There are three main geological zones in the surrounding area, all very different in origin and nature (Figure 1.2). These three zones are: the older rocks inland and to the north of Miletos; the Milesian peninsula; and the Büyük Menderes (ancient Maeander) valley.

The first of the region’s major geological groups occurs to the east of the Milesian peninsula and north and south of the Büyük Menderes valley. This area is composed of granite (or granodiorite – see Gödecken 1988: 308, n. 2), schists, marbles and gneiss. The gneiss constitutes the remains of the Menderes Massif, one of the oldest geological regions in Turkey, consisting of Pre-Cambrian (c. 4,500 to 600 mya) or Lower Palaeozoic (c. 600 to 395 mya) metamorphic augen gneisses, uplifted in the early Alpine Intra-Jurassic phase (c. 195 to 135 mya). This gneiss occurs at Myous and northwards from there up the Büyük Menderes valley. The granite (granodiorite) found to the east of Milesia above Herakleia, and which forms the mass of Mount Latmos and the imposing cliffs of Bafa Gölü, is a result of intrusive volcanics. Marble is found to the east and south of Milesia and is a result of Mesozoic (c. 225 to 65 mya) metamorphism. Topographically this geological zone is mountainous with expanses of exposed rock. It is these rocks that contain the few natural resources to be found anywhere near Miletos.

Figure 1.2 Geological map (after Milet 3.5).

The second geological area is the peninsula of Milesia itself which, in geological timescales, is a relatively young landmass being mostly composed of Neogene (i.e. Miocene, c. 26 to 7 mya, and Pliocene, c. 7 to 2 mya) sedimentary origin. The basic form of the Milesian peninsula is an escarpment with an exposed northern edge and gently-sloping southern side. This is composed mostly of limestone with layers of softer poros (Schröder and Yalçin 1992; Schröder et al. 1995). As the northern edge of this escarpment erodes, it deposits colluvium to create a coastal strip along the north shore thus creating very deep soils in this area, although the top of the escarpment itself is largely barren. On the north side of Milesia is the smaller peninsula on which the city of Miletos itself was built (Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3 The location of the city of Miletos 3D projection seen from the north-west indicating ancient sea-level made using G.I.S. (by the author and John Dodds).

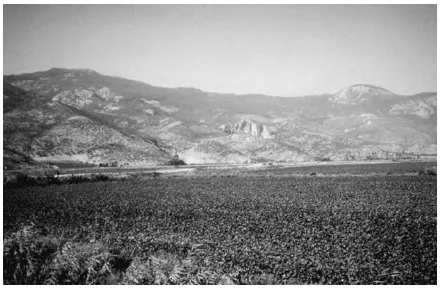

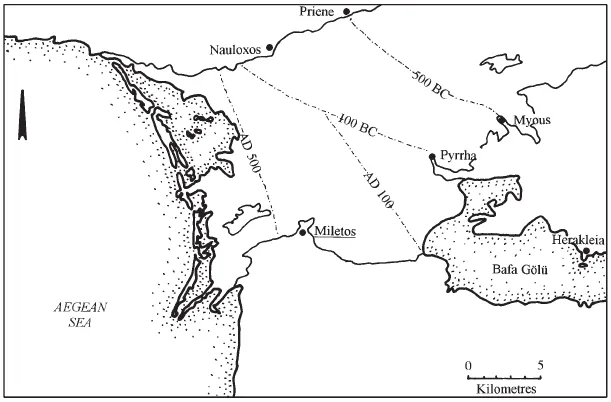

The third geological area, and perhaps the most interesting and important, is the Büyük Menderes valley which runs north-east inland from Miletos. This was created by the collapse of the Aegean sea, an important neotectonic event that created block-faults in western Anatolia, resulting in rift valleys (graben) divided by horsts (Brinkmann 1971: 189). Horsts are high ridges of land formed by faulting and subsidence on either side and tend to be high with precipitous sides, like the Mykale peninsula (modern Samsun Dag). One of these rift valleys was the Büyük Menderes graben, which has a flat bottom and almost vertical sides, best seen in the area around Priene and its striking acropolis. Over time the bottom of this graben, which had been inundated by the sea, has been filled up by the sedimentary action of the Maeander River to create the flat and fertile modern Büyük Menderes plain (Figure 1.4; Aksu et al. 1987a and b). The mouth of the Büyük Menderes has moved progressively southwards and eastwards towards the Aegean due to the large amount of silt being carried down from the mountains (Figure 1.5). Between 500 BC and 500 AD the delta coastline of the Maeander prograded (moved as a result of silting) rapidly within the sheltered Büyük Menderes graben, advancing by between 10 and 17 kilometres in this single millennium. This stopped in c.700 AD when barrier beaches formed across the mouth of the Büyük Menderes graben. Like its neighbour Ephesos, the ancient port of Miletos is now a long way from the sea, at a distance of 7 kilometres. The Büyük Menderes valley can be seen superbly with satellite photography (Peschlow-Bindokat 1996: 19, fig. 5).

Figure 1.4 The Büyük Menderes Plain.

Seismology

Western Anatolia is on the edge of the Mediterranean micro-plate and is subject to frequent plate-tectonic activity, such as the creation of the Büyük Menderes graben and seismic activity, particularly earthquakes. The subduction of the Mediterranean Plate is also the cause of volcanic activity in the Aegean region, including the eruption at Thera in c .1628 BC. This event must have affected Miletos in some way and the LMIA settlement at Miletos appears to have been destroyed by an earthquake, possibly associated with this (Niemeier in Greaves and Helwing 2001). Earthquakes were an important factor in the ancient world (Stiros and Jones 1996) and must also have been a common occurrence in the history of Miletos, although few can be securely identified by archaeology or from historical sources that relate specifically to Miletos. However, it is known that the oracle of Apollo at Didyma was destroyed by an earthquake at some time in the middle ages (Newton 1881: 48). From more recent historical records one begins to understand the frequency with which earthquakes occur in this region. Such records mention earthquakes in this region on 23 February 1653; 25 February 1702 (in Denizli but felt as far as the coast); 20 September 1899 (when in Aydın a 400 metre-long crack opened parallel to the depression); 16 July 1955 (the village of Balat, which then stood on the site of Miletos, was totally destroyed by this and was rebuilt on a new site at Yeni-Balat, meaning “New-Balat”); 23 May 1961; and 11 March 1963 (source: Ergin et al. 1967; Ambraseys and Finkel 1992). The terrible earthquake of 17 August 1999 and the aftershocks that followed are a powerful reminder, if one were needed, of the potent force of earthquakes in Turkey and their potential to adversely affect life in the region.

Pedology

As was noted above (see page), the erosion of the northern edge of the Stephania Hills escarpment has created a coastal strip with deep soils, suitable for arable agriculture. This fertile area adjacent to the ancient city of Miletos must have been one of its great assets in antiquity. The soils of southern Milesia, however, are generally poor and are not deep and well watered enough to be suitable for intensive agriculture. These red and grey-red podsolised soils are only capable of supporting forestry and maquis scrub (Göney 1975: 183). In southern Milesia the majority of soil deposition is limnal, around the coasts (Gödecken 1988: 309), or in the small valleys that occasionally cut into the southern and western edge of Milesia, such as at Deniz Köy. By contrast the deep, hydromorphic alluvial soil of the Maeander valley is extremely fertile and retains moisture well, making it ideal for cereal production (Braun 1995: 32–3). This diverse geology also produced a variety of soils across the region including twenty-seven sources of clay, two of which were exploited for the production of pottery (Gödecken 1988: 315), which has long been recognised as an important productive activity in ancient Miletos.

Figure 1.5 The progradation of the Büyük Menderes Graben (after Aksu et al. 1987b).

Climate

Herodotus observed that Ionia was blessed with a favourable climate, unlike the climates to the north and south, which he considered to be too cold and wet or too hot and dry (Hdt. 1.142). Hippocrates also noted that Ionia was well watered, wooded and fruitful with plentiful harvests and healthy herds (Airs, Waters, Places 12). In Greece, no appreciable climatic change has been proven since ancient times, either through study of the literary sources or through palaeobotanical analysis such as that which has been carried out in Boeotia (Isager and Skydsgaard 1992: 10–11). The Mediterranean continental climate of the Aegean region of Turkey is more apparent than in the Greek peninsula, with hot dry summers and warm wet winters. The region’s dry summers have virtually no rain at all, but 70 per cent of total rainfall is recorded in the winter months between November and March (Aksu et al. 1987b: 231–2; Tuttahs 1995: fig. 74). The Ionian coast and islands receive on average more rainfall than Attika and the arid Kyklades, which are sheltered from the moist westerly winds in autumn and winter by the Pindos mountain range. The steep mountains inland from Miletos, such as Mount Grion (modern Ilbir Dağı, c. 1,200 metres high) and Mount Latmos (Beş Parmak Dağı, 1,375 metres high), rise very steeply from sea level (Peschlow- Bindokat 1996: 12) and catch moisture-bearing clouds carried by the westerly winds that ascend their slopes, cooling them and causing precipitation. The area around Miletos therefore receives more of the rain from these winds than the eastern side of the Greek mainland and low-lying Aegean islands and this must have been a considerable advantage to the city and its agriculture. Even though Miletos is only a few kilometres from the nearest of the Aegean islands its geographical position is such that it has an appreciably different climate and should not be considered just another part of Greece in terms of climate and agriculture.

Hydrology

Other than the Maeander there are no large rivers in Miletos’ territory, but there are many small dry watercourses (ephemerals) that run off the Stephania Hills during the rainy season through small gullies to the west near Akköy and Mavı Şehir. The sloping limestone geology of the Stephania plateau has resulted in a number of natural springs on the northern plain of Milesia (Schröder and Yalçin 1992) and these must have been vital to life and agriculture on the fertile and populous northern plain. One of these springs, named as Byblis by Ovid (Met. 9.450 ff.), may originally have taken its name from the rushes (bubloi) which grew around it (Dunham 1915: 34–5). Until the construction of an aqueduct in the Roman period, transporting water from these springs to the city, Miletos’ water supply must have been met mostly by wells, dug down to a level where the water-bearing limestone meets an impermeable layer of clay (Niemeier, Greaves, Selesnow 1999: 376–8).

In central and southern Stephania there are few naturally occurring springs, and this may account for the seemingly magical nature of the spring which does rise at Didyma and which formed the focus of the oracle there. Occasional seasonal pools form in dips in the surface geology during the wet season and in this otherwise barren land they must be of great importance to the region’s herds and wildlife. A great many wells have been dug in southwest Milesia to compensate for this lack of surface water (Schröder and Yalçin 1992: fig. 2).

Topography and communications

The east–west alignment of the geology of western Anatolia was a major influence on the organisation of its trade routes and the extent and nature of its historical contacts with the civilisations of central Anatolia and the Near East. By contrast, travel from north to south in this part of Anatolia is made difficult by the east–west arrangement of horsts and rift valleys (see above, see page). Although difficult, such routes were not impossible and there existed a track over the Mykale peninsula/Samsun Dagı between Priene and Ephesos and also a less mountainous route from Magnesia-on-the-Maeander to Ephesos (Marchese 1986: 142). There were only a few tortuous routes available through the mountains into south-west Karia and so the valleys such as the Maeander/Büyük Menderes valley created a natural communications corridor deep into the Anatolian interior, which was to be important from prehistoric times onwards (Marchese 1986: 39–42; Melas 1987).

The west coast of Anatolia was the most extreme western point on the exchange route known as the ‘Silk Road’, an enduring process of exchange by land and sea between East and West, which probably began in prehistory but which is difficult to trace archaeologically until the introduction of Roman glass and Chinese ceramics (Mikami 1988). The ‘Silk Road’ followed no particular route and goods from as far away as China and India could reach the sea at any number of coastlines. One of these routes crossed Anatolia to the western coast of Asia Minor and Miletos (Walbank 1981).

Of the possible east–west communication routes across Anatolia, those that used the valleys of the Hermos (to Smyrna) and Kayster (to Ephesos) are thought to have been more used than that which passed down the Maeander to Miletos (Dunham 1915: 1–5, 11–13 and map 2; Birmingham 1961). The construction of the Royal Road from Susa to Sardis boosted the importance of these more northerly routes and when Ephesos was made the Roman provincial capital it still further concentrated trade int...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Milesia

- 2 Prehistoric and Protohistoric Miletos

- 3 The Archaic Period

- 4 Post-Archaic Miletos

- Bibliography