Chapter 1

Theoretical aspects of the main components and functions of attention

Michel Leclercq

Different possibilities exist in relation to the presentation of the numerous and at first sight relatively disparate data coming from research in the attention domain. We propose here a presentation organized on the basis of the main attentional components, an option that in our opinion presents several merits. First of all, and in spite of the apparent heterogeneity of currently available data, it enables both a descriptive and a comprehensive analysis of the different attentional aspects. Indeed, as we will attempt to show, most of the observations emanating from specific research on attention can be gathered and reorganized around the main concepts currently used to describe attentional phenomena. Moreover this type of presentation presents an evident practical interest: it offers those involved in this field a tool which allows them to orient both the type and the methodology of analysis, and so the interpretation of the observations collected; more specifically it allows clinicians to intervene if the case arises, in a manner which is specific, adequate and therefore efficient. Finally, this type of presentation will allow us to detail the main notions specific to each attentional component. Indeed, although an increasingly large consensus is emerging, some confusion still exists about the use of some of these concepts and their specific significance. We hope that this presentation, despite its own limitations, will help to promote this ‘conceptual unity’ and, consequently, will increase the recourse to a common vocabulary for everyone, whether student, researcher or clinician.

We will intentionally limit this presentation to the relatively ‘elementary’ attentional aspects, i.e. those implied in usually simple tasks (detection, analysis and/or selection of not very complex physical or semantic stimuli), to the detriment of the attentional aspects intervening during the resolution of complex situations and requiring highly elaborated cognitive operations such as reasoning, programming, planning, etc. For these latter aspects, we refer the reader to specific publications (among others Cohen, 1993; Shallice, 1988; van Zomeren and Brouwer, 1994).

1 Selective or focal attention

Selective attention corresponds to the most current and common use of the general term ‘attention’: the ability of the subject to process selectively some events to the detriment of others. This corresponds to the first attempt at definition proposed by James (1890):

It is the taking possession of the mind, in clear and vivid form, of one out of what seem several simultaneously possible objects or trains of thought. Focalisation, concentration, of consciousness are of its essence. It implies withdrawal from some things in order to deal effectively with others.

(pp. 403–404)

The multitude of information with which we are continually confronted requires from us prior selection without which we would be totally submerged by stimulations and unable to process any of these efficiently. This imperative necessity of information selection will be at the root of the first attempts at modelling in the attention field.

1.1 Auditory selective attention

The abundance of contemporary studies on visual attention tends to ignore the fact that it was auditory attention that formed the core of the first specific studies, for about fifteen years. Most authors agree in attributing to Colin Cherry (1953) the first systematic studies with a cognitive orientation in the attention field, and more specifically those dealing with selective attention. She developed the paradigm of dichotic listening: an auditory message sent to one ear must be repeated aloud by the subject (‘shadowing’) while a second message which he/she has to ignore is sent to the other ear. By using this technique, Cherry and others after her observed:

- The facilitation of the subject’s capacities of selective attention when messages are spatially distinct (Cherry, 1953); indeed, whereas subjects show marked difficulties in separating two messages stated by the same voice and reaching the two ears simultaneously, they are, however, easily able to discriminate these messages when they are delivered simultaneously, one to the left ear and the other to the right ear.

- Very little information seems to be extracted from the non-relevant message, i.e. the message on which the subject’s selective attention is not focused. For example, one will observe the almost complete absence of memorization of a short list of items integrated into the unattended message, despite the fact that this list was read out more than 35 times (Moray, 1959).

- On the other hand, physical changes, such as the speaker’s gender (Treisman, 1960), the use of a different language for each message (Treisman, 1964), the voice intensity or the arbitrary insertion of a pure sound, were almost systematically detected (Cherry, 1953).

These observations allow us to assert that selective auditory attention is strongly improved by being able to discriminate the physical attributes of the message to be processed; on the other hand, selective discrimination in the binaural task is very difficult when it can only be based on the meaning of messages.

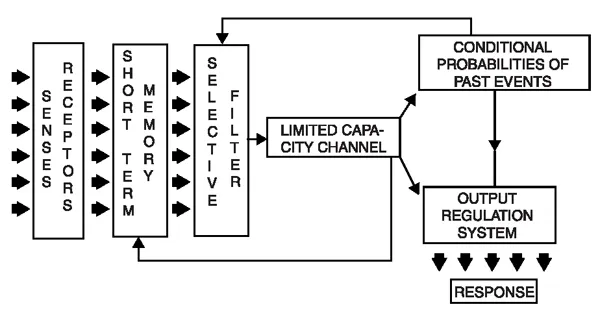

Broadbent (1958) was the first author to propose a model attempting to deal with the totality of data we have just described: the early filtering model. You will find a representation of this model in Figure 1.1. The author based his model on an observation that he considered crucial: the subject repeated aloud according to the spatial origin of the messages. Thus, for example, if A-C-E is delivered in one ear of the patient and B-D-F in his/her other ear, the subject shadowed either ‘A-C-E’ or ‘B-D-F’ according to whether his/her attention was selectively oriented on one or the other message. This observation confirmed quite well the importance of physical attributes – the spatial origin of the message, i.e. the ear to which the message is delivered – to the detriment of other factors such as the sequential chronology; the subject would then have evoked ‘A-B-C’ and ‘D-E-F’, re-establishing the classical chronology. According to Broadbent, this observation proves that the information had been ‘serialized’ by channel. He considered that the nervous system behaves in some ways as a single communication channel which can be considered as having a limited capacity.

The functional description of this model is as follows: the simultaneously presented stimuli or messages reach parallel sensory receptors from which they are transferred into short-term memory. Up to this point, all this information reaching the system is superficially processed in parallel. At this stage, the system has to select among all the stimuli those that will penetrate in the deep and serial channel of limited capacity. This selection will operate from a mechanism of filtering based upon the physical features of inputs. This filtering is adjusted by conditional probabilities of past events stored in long-term memory. The inputs that have not gone through the filter are maintained only a short time in the buffer and vanish quickly if they are not processed. However, a mental repetition loop allows the afferent information to stay in the short-term memory, and this at the expense of the transmission capacity of the serial channel. As Lecas (1992) points out:

Since at the entry of the system the multiplicity of our sensory receptors is organized in parallel and at the exit only one single action is produced out at the time, the postulate of serialty is a logical and reasonable principle for the modellization, to which the notion of overload adds a sort of empirical confirmation.

(p. 44, our translation)

Figure 1.1Broadbent’s filter model (adapted from Broadbent, 1958)

This Broadbent model is qualified as ‘early’ or ‘peripheral’ filtering, as the selection is operating in the first stages of processing and is based on general physical features of the signal.

In spite of a considerable stir in the scientific community, this model was rapidly disproved. Indeed, several studies demonstrated that the selection does not depend only on elementary physical characteristics of the message. Thus, a small modification in Broadbent’s experimentation, considered as crucial by him, completely modifies the results. Indeed, Gray and Wedderburn (1960) used a task version of dichotic listening in which a message, such as ‘Who2 there’, was presented to one ear, while ‘3 goes 9’ was at the same time presented to the other. In this case the preferential order in which the data were repeated by the subjects was not ear by ear but determined by meaning, namely: ‘Who goes there’ followed by ‘3 2 9’. This observation indicates that the selection can operate from aspects other than purely physical characteristics of inputs. The same authors also presented in rapid succession and alternately to each ear some target words fragmented beforehand into syllables. They observed that subjects were able to recognize easily these words. This implies a complete (semantic) analysis of the information from the two ears and a rapid attentional switching by the subject from one channel to the other, the commutation allowing the reconstitution of the fragmented message. Selection possibly based on the meaning is incompatible with the filter theory.

In another study, Allport, Antonis and Reynolds (1972) combined text passages with the learning of words presented auditorily. The recognition performances evaluated at the end of shadowing were haphazard. This absence of memorization was expected on the basis of Broadbent’s filter theory.

However, the authors demonstrated that the memorization became effective when the shadowing task was combined with the visual presentation of the written words. Moreover, when the same task was combined with the presentation of pictures, iconic memorization became excellent (90% success). This observation shows that limitations of simultaneous processing of two inputs are not as rigid as those expected from the Broadbent model. More precisely, if the two inputs are dissimilar, for example according to the sensory modality presentation, it becomes possible to process them simultaneously in a more complete manner than the filter theory predicted.

Moray (1959) carried out research in which he asked subjects not only to repeat aloud the message coming from the attended channel but also, if they heard them, to react to some orders inserted in the unattended channel. Half of these orders were preceded by strongly emotional words such as swear words, the other half being preceded by neutral words. Subjects were able to react to 51% of orders preceded by a highly emotional word, versus only 11% of orders preceded by a neutral word.

In other respects, the importance of the degree of expertise in a dichotic listening task was demonstrated by Underwood (1974) during an experiment in which subjects were asked to attempt to detect a single digit inserted either in the targeted or in the unattended message. Inexperienced subjects detected only 8.3% of the digits inserted in the unattended message, which suggests a very limited processing of this channel. When the same task was performed by Neville Moray, the researcher having submitted himself to many experiences in dichotic listening, he detected 66.7% of the digits inserted in the unattended channel.

Finally, Treisman (1960) carried out research in which the two channels were switched without warning the subjects. Thus, on several occasions, the channel targeted by the subject became the unattended channel and vice versa. The subject’s attention was continuously oriented towards the same headphone, the task being to repeat aloud the delivered message to this ear. The author observed that subjects demonstrated a marked tendency to continue shadowing the unattended message for at least one or two seconds after the channel switching, for as long as the content of the unattended message could constitute semantically the logical continuation of the first one, as in the following example:

Attended channel: leaving on her passage an impression of grace and / is idiotic idea of . . . Unattended channel: singing men and then it was jumping in the tree/ charm and a. . . .

Therefore, none of these observations is compatible with the idea defended by Broadbent according to which selective processing would be limited to purely physical characteristics of the information. Other aspects can be con- siderable determining factors at the selection level, as for example the meaning of the message.

Treisman (1960) proposed a revised version of Broadbent’s model: the attenuator model (Figure 1.2). Instead of totally rejecting the filter notion, she gave it a new function, more ‘nuancé’. Rather than excluding purely and simply the information that did not share some common characteristics with the attended message, she proposed a hierarchical model in which information processing could work at a double level: first, through an ‘acoustical’ filter analysing sensorial inputs from their physical dimensions (intensity, tonality, position, etc.), and undertaking a first sorting before their possible transmission to the recognition system in long-term memory. After this first filtering a discrimination would be operated by the more or less marked raising of the mnesic unit threshold intervening in the recognition. The attenuator works in such a way that only the unattended message elements that have a sufficiently low activation threshold could cross the whole system to be completely processed; the other elements, which did not reach a sufficient activation level, not being processed.

Thus, in the schematic representation in Figure 1.2, thresholds of words B and C will be lowered because of their high occurrence probability after the word A is processed into the target channel. Activation by means of the unattended channel increases the probability that C is heard by the subject. C could possibly be processed because it constitutes ‘a unit in the word-matching system which had been made more sensitive or more available by high transition probabilities’ (p. 247). Thus, in Moray’s experiment (1959) described above, most of the neutral words in the unattended message will never be heard whereas swear words, even attenuated, will activate the appropriate elements and will be completely processed.

Considering that the two levels of the Treisman model are redundant, Anthony and Diana Deutsch (1963) proposed a model directly centred on recognition mechanisms in memory. These authors construct their model on the basis of a collection of neurophysiological data. They consider that all the inputs are completely analysed before any selection. Contrary to the Broad-bent and Treisman models, the filter or bottleneck would be placed downhill from the processing system, just before the emission of response. So, it is here a ‘late’ f...