- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Rural-Urban Interaction in the Developing World

About this book

Sustaining the rural and urban populations of the developing world has been identified as a key global challenge for the twenty-first century. Rural-Urban Interaction in the Developing World is an introduction to the relationships between rural and urban places in the developing world and shows that not all their aspects are as obvious as migration from country to city. There is now a growing realization that rural-urban relations are far more complex.

Using a wealth of student-friendly features including boxed case studies, discussion questions and annotated guides to further reading, this innovative book places rural-urban interactions within a broader context, thus promoting a clearer understanding of the opportunities, as well as the challenges, that rural-urban interactions represent.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Understanding the rural–urban interface

Summary

- Past approaches to development studies have tended to focus on either urban or rural spaces.

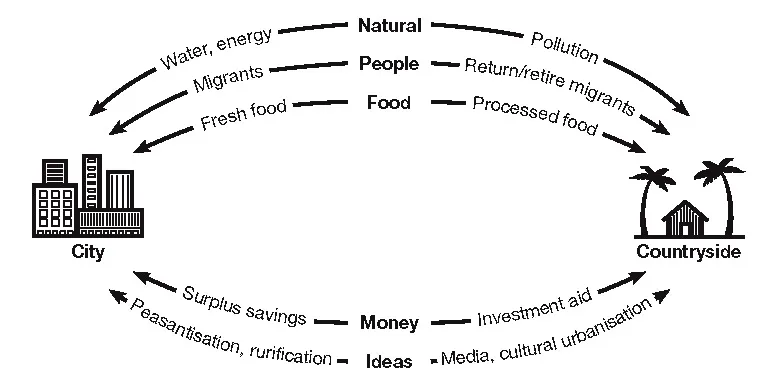

- New development paradigms consider networks and flows, so it is important to reconsider flows and linkages between rural and urban areas.

- Some rural–urban links can favour one area or the other, but it is important to be aware that the net benefits can flow both ways, resulting in change both over time and from one place to another.

- Urban–rural links have been important to development theory although this topic is rarely a focus of development research.

Introduction

Why it is important to study rural–urban interaction

million (UNCHS, 2001). Some of the earliest government actions were designed to impose state-controlled marketing of agricultural goods and rationing of urban food consumption, and to control the movement of people – especially rural–urban migration. In addition, the level of land scarcity experienced by rural dwellers convinced the Chinese government that urban-based heavy industrialisation was the only way the country would be able to support its population which was 541 million in 1952, of whom 57.7 million, or 10.6 per cent, were urban (Knight and Song, 2000). One of the issues that worried the Chinese government was that in 1964, the second census under communist rule found that the urban population had grown to 129.3

million, or 18.4 per cent. Such rapid growth, both nationally and in the cities, alarmed the government, which decided that there was a need to control population growth and to create employment for the urban population.

Box 1.1

Comparing international organisations’ approaches to rural–urban linkages

- the need for a broad analytical framework that can integrate the processes and approaches that span the realms at various scales;

- the need to consider the role that spatial dimensions play, along with the dynamics, vulnerabilities and movements in and out of poverty;

- the importance of a long-term perspective in relation to shifts in settlement and economic patterns;

- recognition that local economies advance and decline and that different approaches may therefore be required, and the need to understand the linkages and their role in the changes;

- the need to recognise the importance of the trend towards decentralisation;

- the need for approaches that facilitate working across sectors;

- the need to recognise the heterogeneity of constructs of town and country and the divisions between them, including agriculture in towns and non-farm activities in the country.

- The poorest areas may have little more than consumption linkages

- Production linkages emerge in more diversified settings, such as where rural-based workshops start to supply urban-based factories

- Financial linkages appear in all settings, but with different outcomes for rural economies

- The rise of network societies may contribute to bypass effects, when financial flows link rural areas directly with distant, larger cities at the expense of local towns.

- (a) ‘To promote the sustainable development of rural settlements and to reduce rural-to-urban migration . . .’ (para.165);

- (b) ‘To promote the utilization of new and improved technologies and appropriate traditional practices in rural settlements development . . .’ (para.166);

- (c) To establish ‘. . . policies for sustainable regional development and management . . .’ (para. 167);

- (d) ‘To strengthen sustainable development and employment opportunities in impoverished rural areas . . .’ (para.168); and

- (e) To adopt ‘an integrated approach to promote balanced and mutually supportive urban–rural development . . .’ (para.169).

- strengthening of rural–urban linkages mainly through the improvement of marketing, transportation and communication facilities;

- improvement of a number of infrastructure components which, while enhancing rural–urban linkages, are also essential for economic growth and employment creation (both farm and non-farm) within small urban settlements and rural areas themselves, especially roads, electricity and water;

- bringing private and public services normally associated with cities to the rural population; and

- strengthening of sub-national governance at the regional, rural-local, and city-region levels.

- Agriculture depends on manufactured goods both for the transformation of produce (for example, farm tools, machinery, inputs) and for the consumer goods which are in demand as agricultural incomes rise (such as radios and bicycles).

- As agriculture incorporates more technology in its activities, labour becomes a less significant factor. More technologically advanced agriculture releases capital and labour which move into the urban industrial sector.

- Agriculture provides raw materials for some industries, such as tobacco, cotton and sisal.

- Agriculture for export can earn foreign exchange which is important for purchasing items which are vital to industrial processes. These include commodities such as petroleum, chemicals and technology which is not produced locally.

- There is an important balance to be struck in incomes, prices and taxation between the urban and the rural areas. For example, high food prices provide rewards to farmers and incentives to increase production, but may mean high prices in urban areas which can lead to poverty and unrest. Taxation in the agricultural sector may be necessary to raise revenues to finance public expenditure, but may act as a disincentive to farmers, particularly if much of the expenditure is urban or industrial focused.

- In rapidly urbanising countries agriculture produces strategically important food for the growing number of urban residents, thus ensuring food security at prices that are affordable.

- Registration records often do not detect changes in residence. For various reasons it may be undesirable for recent in-migrants to be registered as urban dwellers. Rigg gives examples of under-reporting of urban residence, particularly in relation to the controversies this can pose during elections when how an area is defined can have implications for the number of political representatives or the authority into which they are elected (for further discussion of this see Chapter 4 below).

- Allocating people to discrete categories such as ‘urban’ or ‘rural’ assumes that these categories accurately reflect their realities. Rigg’s own empirical research in Thailand (1998b), among others, has demonstrated the significance of fluid, fragmented and multi-location households to survival strategies. This results in households straddling and moving across the rural–urban interface. Thus categorising them as one or the other makes no sense. In addition, there is the problem of defining the boundaries of urban places which is usually done on some arbitrary basis. This will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 4 below.

- Rigg argues that many Asian urban residents do not consider the cities and towns they live in as ‘home’. This is because they ultimately intend to return to their rural origins. This, he argues, brings the issue of the identities of individuals into focus and ‘“home” and “place” are ambiguous and shifting notions, where multiple identities – both – can be simultaneously embodied’ (Rigg, 1998b: 501).

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Figures

- Tables

- Boxes

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. Understanding the Rural–Urban Interface

- 2. Food

- 3. Natural Flows

- 4. People

- 5. Ideas

- 6. Finance

- 7. Conclusion and Future Perspectives

- References

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app