eBook - ePub

Migration And Mobility In Britain Since The Eighteenth Century

This is a test

- 440 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Migration And Mobility In Britain Since The Eighteenth Century

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Poplulation migration is one of the demographic and social processes which have structured the British economy and society over the last 250 years. It affects individuals, families, communities, places, economic and social structures and governments. This book examines the pattern and process of migration in Britain over the last three centuries. Using late 1990s research and data, the authors have shed light on migrations patterns including internal migration and movement overseas, its impact on social and economic change, and highlights differences by gender, age, family, position, socio-economic status and other variables.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Migration And Mobility In Britain Since The Eighteenth Century by Colin Pooley, Jean Turnbull in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Introduction: why study migration?

The significance of migration

Almost everyone moves home at some time in their lives. Together with experiences such as the birth of a child, the death of a relative, marriage, starting a new school and finding fresh employment, moving to a new house is a relatively infrequent but everyday occurrence which, whilst commonplace, can also have wide-ranging ramifications for all concerned. Migration not only affects individuals, and in some cases fundamentally alters people’s lives, but large scale population movement also has implications for wider society, changing population distributions and placing demands on housing, labour markets and services. Such consequences stem most obviously from mass flows of refugees or migrants fleeing events such as famine or war, but even short distance movement within national boundaries can have significant and wide ranging impacts (Black and Robinson, 1993). Moving home is also a complex process, undertaken for a large number of different reasons, and causing many potential difficulties or disruptions which have varied effects on members of a mobile household.

This was no less true in the past than it is in the present; but because much migration left little in the way of written records, and because the reasons for and impacts of residential movement are so varied and personal, we know relatively little in detail about migration in the past. However, where oral or written testimonies exist it is possible to gain some inkling of the significance of moving home.

Much migration was undertaken for work, and for some this seemed a relatively unproblematic event. In the early-twentieth century, Trafford Park in Manchester was being developed as a massive industrial estate with associated housing for workers. Labour migrants were attracted to new opportunities in Manchester and Salford from a relatively wide area:

My parents—they were in Liverpool, on the docks. Me father was a ships’ carpenter and there was no work whatsoever, and he got the information that there was work on the docks at Salford and he got a return ticket, half a crown, and he came and he got took on the same morning. In the evening he sent a telegram to me mother: ‘Come, I’ve got a job and somewhere to live’. And thats the way they started, they came there with nothing—only bits of essentials in a bag. (Russell and Walker, 1979, p. 6)

Knowledge about new work opportunities could spread in many ways and, in some instances, employers deliberately recruited workers to fill a labour shortage. Thus in the late-eighteenth century, rural textile mills in North Lancashire attracted workers with domestic textile skills from the surrounding region:

Mr. Edmondson the managing master came over to dent to engage hands, several more families hired, & among the rest my father and family—we were 7 childrer & they liked large families the Best for the Childrers sake—my father engaged for him & me to work in the machanic shop, at our trade &c—So my father Sold the greater part of his goods, &some he left unsold, & came to this dolphinholme, with some others in July 1791. (Shaw life history, see Appendix 1)

Even when work was readily available, and movement was undertaken as a family group in conjunction with others from the locality, migration could cause some trepidation and concern:

this leaving our own Countery [the move was only around 50 km] was a great cross to my mother, for she was greatly atached to her Native town, & had she known what would follow, I am sure that she never would have left her relations & countery on any account. (Shaw life history)

However, for some migrants emigration to the other side of the world was undertaken with enthusiasm and encouragement to others:

i am sure that if laboren people ad the least idea of the colney they would not work hard in Ingland to starve whear in the colnies thear is plenty for whe ave plent of wheat and mutton and biefe and evrey thinks that whe can whish for the onley thing is crossing the salt waiter. (Richards, 1991, p. 25)

Even with short distance migration, undertaken with optimism by a 16-year-old migrant moving some six km in London, moving away from home could cause understandable unhappiness and concern amongst relatives left behind:

Upon the appointed day May 10th 1858 my poor mother took me over and duly delivered me to my new masters, returning home alone. I cannot say that parting from those at home caused me any great sorrow. I felt most for my mother—and she felt my going away acutely. As for me, I was full of anticipation. (Jaques life history)

Such relatively rare testimonies provide evidence of the human impacts of migration. The research presented in this book combines a wide range of sources in an attempt to paint a broader picture of the ways in which moving home has affected people, places and wider society in Britain since the mid-eighteenth century.

One measure of the significance of migration is its volume. Although the British population censuses do not provide evidence for the total number of moves undertaken in an individual’s life-time, birthplace statistics do indicate the extent to which people had moved outside their county of birth at a particular point in time (Baines, 1972, 1978). This is a poor surrogate for migration, combining long distance moves from one part of the country to another with short distance moves across a county boundary, ignoring movement within counties, and giving no inkling of life-time residential histories. However, even such flawed evidence indicates the extent to which people were mobile in the past. Thus in 1851, the more industrial regions such as Central Scotland, South Wales, North-West England and the West Midlands had more than a quarter of their population born outside their county of residence. London attracted the largest number of migrants from all over Britain (38.3 per cent of its population had been born outside London in 1851), but cities such as Glasgow (55.9 per cent), Liverpool (57.5 per cent), Manchester (54.6 per cent) and Birmingham (40.9 per cent) contained proportionately more migrants. By 1911, South-East England was attracting the largest numbers of migrants, with over 40 per cent of the population of many southern counties born outside their county of enumeration, but even in the older industrial regions of Central Scotland, South Wales and North-West England over one third of the population had been born in a county which was different from the one in which they lived on census night. This limited census evidence suggests that migration was a common experience for a large proportion of the population (Langton and Morris, 1986, pp. 10–29).

Although experienced by a smaller number of people, emigration overseas, especially to the British colonies in the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, was also a relatively common occurrence. Dudley Baines (1985) has calculated the volume of emigration from English and Welsh counties in the nineteenth century, and argues that although proportionately the greatest volume of emigrants left from impoverished rural areas, a quantitatively larger volume of emigrants originated in urban areas, although many of these may have been previous rural to urban migrants. Emigration had a particular impact on the demography of Scotland. The Highlands experienced an absolute loss of some 44,000 people from 1851 to 1961, and throughout the nineteenth century Britain as a whole experienced a net loss of population through emigration. In total, possibly some 11,662,300 people emigrated from England, Wales and Scotland between 1825 and 1930 (Baines, 1985, pp. 299–306; Harper, 1988; Erickson, 1994).

Immigration to Britain from overseas has an impact both on the individual who moves and on the communities which absorb newcomers who may bring with them different customs and beliefs. In the nineteenth century, the largest volume of immigration came from Ireland (although in some respects this should be viewed as internal migration). Many British cities had substantial Irish communities, and the Irish population generated considerable hostility and experienced prolonged discrimination (Swift and Gilley, 1985; 1989; Davis, 1991). Immigrants from elsewhere in the world were relatively few in number, and mainly concentrated in port cities such as London, Bristol, Liverpool, Newcastle and Glasgow (Holmes, 1988). In the twentieth century, and especially after the Second World War, Britain experienced substantial waves of labour migrants from its former colonies as immigrants from Asia and the Caribbean were encouraged to come to Britain to fill the post-war labour shortage (Walvin, 1984; Panayi, 1994). By the 1960s, London and many provincial cities had substantial communities of immigrants who had often brought with them their own customs, religion and culture. In the late-twentieth century, Britain is a truly multi-cultural society, although many immigrants and their children continue to experience similar problems to those faced by Irish migrants in the nineteenth century (Robinson, 1986; Peach, 1996).

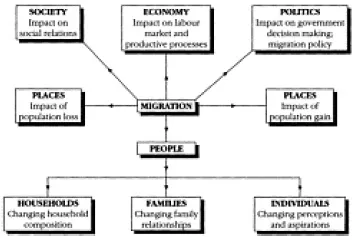

Whilst the extent of population movement is undeniable, if sometimes difficult to pin down precisely in the past, the implications are more difficult to formulate. It can be suggested that all residential mobility has significance at three distinct levels: impacts on the individual and his/her family, impacts on places which lost and gained migrants, and impacts on wider social, economic and political structures. Figure 1.1 summarizes some of the connections between these different layers, and suggests that migration was central to the process of social, economic and cultural change in the past. At the societal level, population movement transferred labour to new sites of industry, restructured labour markets and affected the viability of new industrial ventures. In places where migrants concentrated, the social and cultural structure of society was changed as people with different outlooks and beliefs mixed on the streets and in workplaces. In some instances, large scale migration (such as Irish famine migration into mid-nineteenth century Britain) stimulated governments to develop specific migration policies or to use existing economic and social policy to target particular migrant groups. All places were affected by migration, and all locations both gained and lost migrants over time, but where there was an imbalance between in- and out-movement, this could have a significant effect upon demographic and community structures. Some communities were left with an ageing population and diminished labour resources, whilst others suffered overcrowding, labour surpluses and housing shortages. Impacts at the individual level were the most varied and hard to define, but it can be suggested that the process of migration broadened horizons, changed attitudes and altered the nature of relationships between family members as kin became more widely scattered around the country. However, the ways in which individuals reacted to such changes varied from person to person and cannot easily be generalized.

Figure 1.1 Diagram of the significance of migration for people, places and society

It can be suggested that the process of population migration is of particular relevance to cultural change. If culture is about the sharing of meanings, and the ways in which different individuals and groups make sense of the world in which they live, then the process of migration—which brings different groups of the population together—is central to the process of sharing and mixing which creates cultural change. The links between migration and cultural change are most marked where immigration has brought groups with distinctive cultural characteristics into the country. Thus, Irish migrants into nineteenth-century cities had difficulty adjusting to an English urban way of life, and experienced significant hostility to their culture. This was clearly expressed by a Liverpool Medical Officer of Health commenting on Irish funeral customs:

The three houses were crammed with men, women and children, while drunken women squatted thickly on the flags of the court before the open door of the crowded room where the corpse was laid. There had been, in the presence of death, one of those shameful carousals which, to the disgrace of the enlightened progress and advanced civilization of the nineteenth century, still lingers as dregs of ancient manners amongst the funeral customs of the Irish peasantry. (Trench, 1886, p. 23)

New Commonwealth migrants to Britain since the 1950s have had similar experiences and, despite an initial desire to assimilate to British culture, have met with sufficient hostility to encourage second and third generation immigrants to look more towards their Afro-Caribbean and Asian origins for cultural support than to British society. A Punjab-born man who came to Bradford in 1956 at the age of two recalls his schooldays:

And I can remember vividly at Belle Vue one time when the Asian boys had to band together and march down the road as a phalanx column …to ensure their own safety. And I can also remember…things about skinheads coming to Bradford and beating up Asians and black people. And I can remember, you know, things about repatriation, and …leaflets going round school which were from something called the, was it ‘The Yorkshire Campaign against Immigrants?’…which said things like, ‘If you sit against, sit next to an Asian in a class you are bound to catch smallpox’ and things like this. So yes, I was becoming more and more aware of myself, what I was, and, and these things that were happening…(Perks, 1987, p. 70)

In these instances the process of migration has fundamentally influenced both the lives of individual migrants and the nature of the society in which migrant communities have formed.

In the late-twentieth century we are increasingly aware of the processes which are creating a global society and economy. Easy communication, instant world news coverage and global marketing by multinational companies has meant that many people experience much the same influences wherever they are in the world. Population migration is part of this globalizing tendency, as at least some people move easily over long distances and, in Europe, economic and political integration has lessened barriers to movement (King, 1993; Hall and White, 1995; Clark, 1996). However, despite such trends, migration remains traumatic and difficult for some. There are increased barriers in Europe to refugees and those seeking political asylum, and the extent to which people are attached to particular places in which they have lived much of their lives remains significant. Thus refugees from zones of conflict such as the former Yugoslavia have experienced massive problems of dislocation and cultural adjustment (Glenny, 1993). For most people in late-twentieth century Britain the most important migration experience remains a short distance move within a particular locality, and attachment to place is likely to be an important part of cultural identity (Stillwell, Rees and Boden, 1992). Although the ways in which such processes operated may have changed over time, conflicts between globalizing and localizing influences—as migrants were stimulated to move by increasing opportunities and easier transport, but to some extent restrained by attachments to people and places within one locality—were as important in the past as in the present.

What is migration?

Although almost everybody experiences migration, and most people think that they know what it is, the definition of migration is not straightforward. Whereas other demographic events—notably births and deaths—are finite, clearly defined, and therefore relatively easy to measure, migration is ‘a physical and social transition and not just an unequivocal biological event’ (Zelinsky, 1971, p. 223). Apart from the fact that migration necessarily involves physical movement through space, there is little other agreement about what precisely constitutes migration.

The terms migration and mobility are often used interchangeably, but mobility is, if anything, an even more loosely defined term. It is possible to suggest that, during a lifetime, any individual will undertake a variety of types of mobility. These could range from very short distance daily moves within a locality for social or educational purposes, through journeys to work which may be over considerable distances, short distance residential moves in which a person changes house but remains part of the same community, longer distance residential moves to another part of the country, to emigration to a new home on the other side of the world. Although such a classification also implies a division between temporary and permanent movement, clear-cut definitions are illusory. Whilst we are alive, few moves are truly permanent, and much residential change may involve population circulation, as people migrate between two locations perhaps related to seasonal employment opportunities or as students attending college during termtime but living elsewhere during vacations. Some people live in one location during the working week and elsewhere at weekends, whilst temporary visits to relatives can become prolonged if, for instance, there is need to care for a sick parent. The space-time categorization of different aspects of mobility thus becomes rather fuzzy at the edges, and it is not possible to draw clear definitional lines in terms of distance moved or degree of permanence.

In studies of contemporary and past migration many different definitions have been used. Data constraints sometimes require migration to be defined simply as a move which crosses an administrative boundary, and which therefore is recorded as a statistic (for example Friedlander and Roshier, 1966). This is clearly unsatisfactory, especially where administrative units are large and/or variable in size. Other studies define migration as residential moves which also require a change in community affiliation and employment, thus excluding short distance intra-urban moves. Such definitions focus attention on the links between migration, community adjustment and wider society, but ignore the personal and local impacts of frequent short distance mobility (Bogue, 1959, p. 489). A broader definition of migration is one which includes all ‘permanent or semi-permanent change of residence’ with no restriction on distance moved (Lee, 1966, p. 49). Although, as noted above, the term permanent itself raises definitional problems, this seems a more appropriate definition.

In this book, migration is defined in its widest sense to include all changes of normal residence, irrespective of the distance moved or the duration of stay at an address. Thus movement to go on holiday or to visit friends for a few days or even weeks is excluded, but any move of personal possessions and household effects to a new location, even if this is only for a few days, is counted as a residential move. Non-residential mobility is excluded from the study, although some data on the relationship between home and workplace has been collected and is briefly analyzed in Chapter 5. Further information on how data were collected and defined is presented in Chapter 2. At all stages the term migration is use...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Chapter 1: Introduction: Why Study Migration?

- Chapter 2: How to Study Migration In the Past

- Chapter 3: Where People Moved: The Spatial and Temporal Pattern of Internal Migration In Britain

- Chapter 4: The Role of Towns In the Migration Process

- Chapter 5: Migration, Employment and the Labour Market

- Chapter 6: Migration, Family Structures and the Life-Course

- Chapter 7: Migration and the Housing Market

- Chapter 8: Migration As a Response to Crisis and Disruption

- Chapter 9: Overseas Migration, Emigration and Return Migration

- Chapter 10: The Role of Migration In Social, Economic and Cultural Change

- Chapter 11: Conclusion: A Broader Perspective On Migration and Mobility In Britain

- Appendix 1: Diaries and Life Histories Used In the Research

- Appendix 2: Family History and Genealogy Societies Co-Operating With the Research Project

- Appendix 3

- Appendix 4: Details of Variables Included In Three Data Entry Tables

- Appendix 5: Maps of Movement Into, Out of and Within Each Region

- Appendix 6A: Matrix of Movement Between Settlements of Different Size, 1750–1839

- Appendix 6B: Matrix of Movement Between Settlements of Different Size, 1840–79

- Appendix 6C: Matrix of Movement Between Settlements of Different Size, 1880–1919

- Appendix 6D: Matrix of Movement Between Settlements of Different Size, 1920–94

- Bibliography