This is a test

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Virtue Ethics and Moral Education

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This collection of original essays on virtue ethics and moral education seeks to fill this gap in the recent literature of moral education, combining broader analyses with detailed coverage of:

* the varieties of virtue

* weakness and integrity

* relativism and rival traditions

* means and methods of educating the virtues

The rare collaboration of professional ethical theorists and educational philosophers provides a ground-breaking work and an exciting new focus in a growing area of research.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Virtue Ethics and Moral Education by David Carr,Jan Steutel in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

Introduction

1

Virtue Ethics and the Virtue Approach to Moral Education

Introduction

Different approaches to moral education – distinguished, as one would expect, by reference to diverse conceptions of moral educational aims and methods – are to be encountered in the research literature of moral education. In the sphere of psychological theory and research, for example, somewhat different moral educational emphases – on parental influence, behaviour shaping, dilemma discussion – appear to be characteristic of (respectively) psychoanalytic, social learning and cognitive developmental theory.

In general, however, it is arguable that differences between conceptions of moral education are nothing if not philosophical. Thus, notwithstanding modern psychological attempts to derive moral educational conclusions from quasi-empirical research alone, it is difficult to see how such conclusions might be justified without appeal, however covert, to specific epistemological, ethical and even political considerations. Indeed, such familiar modern moral educational approaches as values clarification and cognitive-stage theory – though clearly inspired by psychological research of one sort or another – do not in the least avoid controversial conceptual, normative and/or evaluative assumptions and commitments. The allegedly ‘impartial’ goal of values clarification, for example, appears to enshrine a deeply relativistic moral epistemology, and cognitive stage theory seems ultimately rooted in liberal ethical theory. Again, more recent moral educational conceptions – associated with ideas of just community, character development and caring – also appear to be fairly philosophically partisan.

In addition to the accounts just mentioned, however, there is evidence of renewed and mounting interest in another, actually more ancient, approach to moral education: which, because it focuses on the development of virtues, may be called the virtue approach to moral education. As in the case of other moral educational perspectives, the virtue approach is rooted in a philosophical account of moral life and conduct from which educational aims stand to be derived. All the same, it is not entirely clear that current interest in the virtue approach to moral education has been attended by widespread appreciation of the philosophical status and logical character of the associated philosophical perspective of virtue ethics. One consequence of this has been a tendency to confuse the virtue approach to moral education with such quite different accounts as character education, the ethics of care and even utilitarianism. So, in the interests of disclosing the distinctive features of the virtue approach, we need to be rather clearer about the philosophical claims of virtue ethics.

Thus, by way of introduction, we shall try – via exploration of a range of alternative definitions – to chart the conceptual geography of virtue ethics and the virtue approach to moral education. Our main aim will be to try to distinguish different ways in which moral education may be held to be implicated in the development of virtues, diverse conceptions of virtue ethics, and ultimately, what a distinctive virtue ethical conception of moral education might be coherently said to amount to. Although no complete summary of the various contributions to this volume will be given in this introduction, reference here and there to the views of contributors is made for purposes of illustration.

The Virtue Approach: Broad and Narrow Senses

At first blush, it might be suggested as the principal criterion of a virtue approach that it takes moral education to be concerned simply with the promotion of virtues. On this criterion, a virtue approach is to be identified mainly by reference to its aims, all of which are to be regarded as virtue-developmental, or at any rate, as primarily focused on the promotion of virtues. What should we say of this criterion?

Despite modern controversies concerning the status of particular qualities as virtues, a reasonably uncontroversial general notion is nicely captured by George Sher’s (1992: 94) characterization of virtue as a ‘character trait that is for some important reason desirable or worth having’. According to this description, although such qualities as linguistic facility, mathematical acumen, vitality, intelligence, wit, charm, joie de vivre and so on are rightly considered of great human value, they cannot be counted as virtues, because they are not traits of character. On the other hand, although such qualities as mendacity, cowardice, insincerity, partiality, impoliteness, maliciousness and narrow-mindedness do belong to the class of character traits, we cannot regard them as virtues because we do not see them as worthwhile or desirable.

Given this general concept, although our first tentative criterion of a virtue approach to moral education does not exclude the possibility of different or even rival virtue approaches, it clearly excludes any approach which does not take moral educational aims to be mainly concerned with the promotion of desirable or admirable character traits. However, insofar as several approaches to moral education mentioned earlier in this introduction would seem to satisfy this initial criterion, one might well wonder whether it is quite demanding enough. Advocates of character education, for example, also define moral education in terms of cultivating virtues and their constituents. The criterion arguably applies even to Lawrence Kohlberg’s well known cognitive development theory (Kohlberg 1981), for while at least early Kohlberg was explicitly opposed to any ‘bag of virtues’ conception of moral education – of the kind beloved of character educationalists – he nevertheless regarded the promotion of one virtue, the abstract and universal virtue of justice, as the ultimate aim of moral education.1 Thus, in pursuit of a more discriminating account of a virtue approach to moral education – one which promises to do rather more conceptual work – we need to tighten the initial criterion.

One promising route to this might be to identify some particular moral theory as the ethical justification or ground of a virtue approach. In short, we might regard as a virtue approach to moral education only one which is based on virtue ethics, as opposed to (say) utilitarianism or Kantianism. But what exactly might it mean to found a conception of moral education on an ethics of virtue? Since the very idea of a virtue ethics is itself contested, we may now be vulnerable to the charge of attempting to explain what is already obscure in terms of what is yet more obscure: unless, that is, we can further clarify what might be meant by an ethics of virtue.

We might make a start on this by defining virtue ethics – formally enough – as a systematic and coherent account of virtues. On this view, it would be the aim of such an account to identify certain traits as desirable, to analyse and classify such traits and to explain their moral significance: more precisely, to justify regarding such traits as virtues. Accordingly, to regard virtue ethics as theoretically basic to a conception of moral education, would presumably be to conceive moral education as a matter of the development of such traits, along with promotion of some understanding of their moral value or significance. Hence, whereas the initial criterion takes a virtue approach to moral education to consist in cultivating virtues and their constituents, our elaborated criterion makes a coherent and systematic account of those virtues a condition of the virtue approach.

All the same, this definition of virtue ethics is still a fairly broad one, an account with, as it were, very large scope and relatively little conceptual content. As yet the definition is quite wide enough to comprehend even utilitarian or Kantian views as instances of virtue ethics. Thus, in Moral Thinking (1981) R. M. Hare – whose ideas draw heavily on both the Kantian and utilitarian traditions – offers a systematic and substantial account of moral virtues. Drawing a valuable distinction between intrinsic and instrumental moral virtues, Hare takes courage, self-control, temperance and perseverance to be examples of the latter and justice, benevolence, honesty and truthfulness to be instances of the former. Thus, as the bases of our prima facie moral principles, intrinsic virtues are to be regarded as not just instrumental to, but constitutive of, the moral life. Moreover, Hare provides a detailed account of their moral significance: both kinds of virtue are to be justified by critical thinking on the score of their ‘acceptance-utility’.

Again, in his Political Liberalism (1993), John Rawls gives a systematic and coherent account of a clearly articulated set of virtues in the context of a basically neo-Kantian conception of moral life, considering such traits of character as tolerance, fairness, civility, respect and reasonableness as crucial to peaceful coexistence in conditions of cultural diversity. However, a more fine grained taxonomy of moral virtue is also a feature of his account. Thus, Rawls distinguishes civic or political virtues – those presupposed to the effective functioning of liberal-democratic polity – from the virtues of more particular religious, moral or philosophical allegiance. Whereas the latter may have an important part to play in personal and cultural formation, the former are indispensible to the social co-operation required by his principles of justice. These principles are themselves justified from the perspective of the original position or on the basis of wide reflective equilibrium.

In sum, our formal definition of a virtue ethics still appears to cover too much ethical ground. Indeed, it is not just that it lets in neo-Kantians. We could even argue that Kant himself is a virtue ethicist in the sense defined to date, since in the second part of his Metaphysik der Sitten (1966[1797]) he offers an account of virtue as a kind of resistance to the internal forces opposing moral attitude or will. In brief, the virtuous person is depicted as the one with sufficient strength of mind to obey the moral law in the teeth of counter-inclinations.

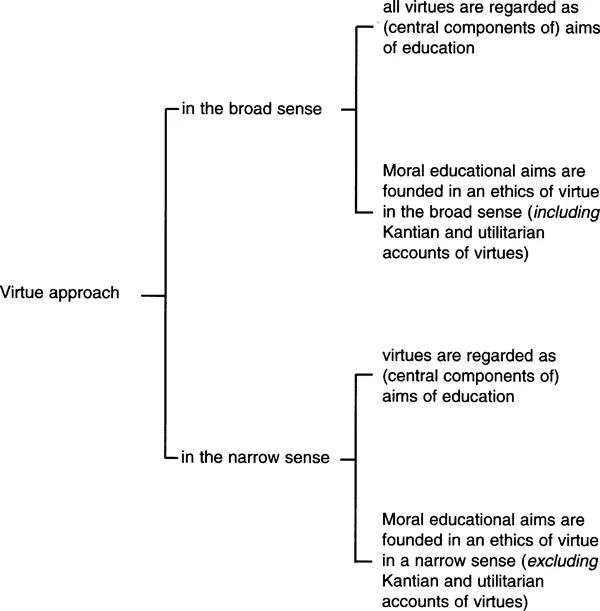

But if we define virtue ethics in such a broad sense, our definition of the virtue approach to moral education must also be a broad one, given that the former is, according to our second criterion, theoretically basic to the latter. Thus, for example, any conception of moral education which endorsed Hare’s account of the nature and ethical value of intrinsic and instrumental virtues would be a case of a virtue approach. If Kohlberg’s conception of moral education, at least in its final post-conventional stage, is based on a Kantian account of the virtue of justice (as Paul Crittenden plausibly argues in his contribution to this volume) his conception of moral education would also have to be construed as a virtue approach. Such considerations, however, point to the need for a less formal and more substantial interpretation of our elaborated criterion and to a narrower definition of virtue ethics. This would exclude Kantian and utilitarian moral views (and, for that matter, other deontological and consequentialist theories) as well as any and all conceptions of moral education (including Kohlberg’s) which are clearly grounded in Kantian and utilitarian ethics. (See Figure 1.1.)

Figure 1.1 The virtue approach in the broad and the narrow sense

Our initial criterion of a virtue approach referred only to certain general features of the aims of moral education, while the elaborated criterion related more directly to matters of justification. We have also seen that the elaborated criterion of virtue ethics admits of broad and narrow construals. On the broad interpretation, a virtue ethics certainly requires us to provide an ethical justification of virtues – some account of their moral significance – but on a narrow interpretation, the ethics of virtue points to a justification of a particular kind: one which grounds moral life and the aims of education in other than utilitarian or Kantian considerations.2

The Aretaic Basis of Virtue Ethics

From now on we shall focus – unless otherwise indicated – on the virtue approach defined according to a narrow sense of virtue ethics. Despite philosophical disagreements of detail concerning the precise nature of an ethics of virtue – there would appear to be broad agreement on one important point: that insofar as it is proper to regard ethical theories as either deontic or aretaic, a virtue ethics belongs in the second of these categories. This classification, in turn, is ordinarily taken to depend on the possibility of a reasonably clear distinction between deontic and aretaic judgements.3

The term ‘deontic’ is derived from the Greek deon, often translated as ‘duty’. Such judgements as ‘one should always speak the truth’, ‘one ought to keep one’s promises’ and ‘stealing is morally wrong’ are typical deontic constructions. ‘Aretaic’ is derived from the Greek term for excellence, arete. Such judgements as ‘she has great strength of character’, ‘her devotion is admirable’ and ‘spite is most unbecoming’ are examples of aretaic locutions. These two types of judgement differ most conspicuously with respect to their principal topics of discourse: whereas deontic judgements are primarily, if not exclusively, concerned with the evaluation of actions or kinds of actions, aretaic judgements are also concerned with the evaluation of persons, their characters, intentions and motives. This distinction is not entirely hard and fast since actions may be the subject of either deontic or aretaic judgements. But although actions are also subject to aretaic evaluation, such appraisal seems to differ from deontic evaluation insofar as an appeal to rules or principle is a salient feature of the latter. Hence whereas characterising an action as morally wrong suggests that performing it is contrary to some general rule or principle, the focus in aretaic judgements about actions, is more on the psychological or personal sources of agency. To call an action bad or vicious, for example, is to draw attention to the bad inclinations or vicious motives from which it springs.

Again, aretaic predicates (‘good’ and ‘bad’, ‘admirable’ and ‘deplorable’, ‘courageous’ and ‘cowardly’ etc.) differ from deontic predicates (‘right’ and ‘wrong’, ‘obligatory’, ‘permissible’ or ‘prohibited’ etc.) by virtue of expressing what can be referred to as scalar properties. To be good or admirable, for example, is to possess a comparative quality, since we can speak of better and best, more or less admirable. However, since we lack the comparatives right, righter and rightest – presumably because no very clear sense attaches to appraisal of actions as more or less right – rightness is not a scalar quality (Urmson 1968: 92–6). To this extent deontic evaluations may appear, by contrast with aretaic appraisals, to resemble legal judgements, and, indeed, this difference is well explored in Nicholas Dent’s insightful contribution to this volume. Whereas moral qualities may be expressed either deontically (by identifying actions as right or obligatory, wrong or forbidden) or aretaically (by identifying actions as friendly or considerate, hostile or unkind), Dent nevertheless shows how the former kinds of characterization incline to a quasilegal construal of moral imperatives as externally imposed demands or unwelcome constraints.

At any rate, this distinction between deontic and aretaic judgements gives us some purchase on the difference between a deontic and an aretaic ethics. It is characteristic of an aretaic ethics that: first, aretaic judgements and predicates are treated as basic or primary, at least in relation to deontic ones; second, deontic judgements and predicates are regarded as, if not inappropriate or redundant, at least derivative of, secondary or reducible to aretaic ones. The same holds mutatis mutandis for deontic ethics.

It should also be clear, however, that these definitions license a distinction between two versions of an aretaic ethics, and by implication, two versions of virtue ethics. On the first version – which might be called the replacement view – the claim is that deontic judgements and notions are inappropriate or redundant and should be jettisoned in favour of aretaic ones. Elizabeth Anscombe in her widely celebrated and much discussed paper ‘Modern moral philosophy’ (1958) seems strongly drawn to some such radical thesis in observing that contemporary philosophers would do well to suspend enquiry into notions of moral rightness and obligation – given their source in a divine law conc...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Series

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Figures

- List of Contributors

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Virtue Ethics and the Virtue Approach to Moral Education

- General Issues

- Virtue, Eudaimonia and Teleological Ethics

- Character Development and Aristotelian Virtue

- Virtue, Phronesis and Learning

- Varieties of Virtue

- Cultivating the Intellectual and Moral Virtues

- Virtues of Benevolence and Justice

- Self-Regarding and Other-Regarding Virtues

- Weakness and Integrity

- Moral Growth and the Unity of the Virtues

- The Virtues of Will-Power Self-Control and Deliberation

- Virtue, Akrasia and Moral Weakness

- Relativism and Revial Traditions

- Virtue, Truth and Relativism

- Justice, Care and Other Virtues A Critique of Kohlberg's Theory of Moral Development

- Liberal Virtue and Moral Enfeeblement

- Educating the Virtues Means and Methods

- Virtues, Character, and Moral Dispositions

- Habituation and Training in Early Moral Upbringing

- Trust, Traditions and Pluralism Human Flourishing and Liberal Polity

- Conclusion

- The Virtue Approach to Moral Education Pointers, Problems and Prospects

- Index