This is a test

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Organised Crime and the Challenge to Democracy

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This innovative book investigates the paradoxical situation whereby organized crime groups, authoritarian in nature and anti-democratic in practice, perform at their best in democratic countries. It uses examples from the United States, Japan, Russia, South America, France, Italy and the European Union.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Organised Crime and the Challenge to Democracy by Felia Allum,Renate Siebert in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Definitions and diatribes

1

Why is organized crime so successful?

Fabio Armao

The rate at which the mafia problem is exploding in an ever-growing number of countries, both developed and developing, challenges our understanding over and above our moral principles. We were used to thinking of organized crime as a marginal phenomenon and/or as the sign of closed social groups contrasting the flow of modernization. Now we must assume that criminal organizations act just as private holdings, produce huge profits, enter more and more markets—becoming transnational—without ever losing their main characteristic, which is the use of violence to conquer and defend their positions. But, first of all, what exactly do we mean by ‘organized crime’ and, second, how is it possible that organized crime may succeed in challenging even modern democracies?

Organized crime: a genus with a plurality of species

As is well known, the expression ‘organized crime’ was coined during Prohibition and legitimized by the Kefauver Commission on interstate criminal commerce in the United States in 1951 (Becchi 2000). The term emphasizes the economic aspects of the crime, its pursuit of illicit profits through group activity; and many have argued that the group has ethnic consistency, which implies that crime is an instrument of social advancement for underprivileged minorities (Abadinsky 1990). Lastly, in December 2000 this definition was adopted by the United Nations in its Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime: an “‘Organized criminal group” shall mean a structured group of three or more persons, existing for a period of time and acting in concert with the aim of committing one or more serious crimes or offences…in order to obtain, directly or indirectly, a financial or other material benefit’ (article 2). But such a definition proves to be oversimplistic because, by decontextualizing transnational organized crime from political and social reality, it impedes comprehension of its origins, and, in so doing, it conceals the fact that its competitiveness may also consist in a traditional network of collusive relationships with members of external (and licit) groups (social, political, entrepreneurial). Besides, it ignores significant differences among organizations, such as white-collar criminals, street gangs, mafia.

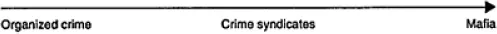

It might be useful, at least for social scientists if not for politicians and investigators, to consider and define organized crime as a genus, including many different species depending on the geopolitical and historical context. In other words, we may imagine a sort of continuum, starting from organized crime in the sense of a group of individuals who act together to commit crimes of different types (such as robberies, drug pushing, etc.), even on a transnational basis; then moving on to crime syndicates as well-structured criminal groups with different hierarchical roles devoted to the search for profits, acting first of all as entrepreneurs; and finally at the other end of the continuum mafia, as the most specialized criminal group, also using politics (which means the totalitarian control of a territory) to obtain profits (see Figure 1.1).

Theoretically, of course, it is possible to move up or down the continuum; thus it is not necessary that all organized crime groups evolve into mafia, and even mafia groups may be able to cut their links with political systems and become more involved in business activities (just like criminal entrepreneurs). Empirically, which means historically, things are much more complex. First, to study transnational organized crime it is necessary to effect a sort of methodological revolution, adopting at least some of the assumptions about multidisciplinarity and multilevel analysis on which social scientists theorize, while at the same time looking at these assumptions as if they were utopian goals. Organized crime is probably the best case study to test this method. A grid to organize the many different variables would be needed and it would also be necessary to collect empirical data, to obtain ever more information on different organizations: their structures, businesses, relationships with the political systems, and so on. But the last point is still, paradoxically, the most difficult one: many governments are reluctant to inform us about the true extent of the phenomenon inside their borders and tend to interpret requests for data and information, even from international institutions, as a gross violation of their sovereignty.

However, if we had sufficient facts we could test a number of hypotheses. Maybe in certain circumstances a sort of ‘natural’ trend exists and the mafia is the point of arrival, a ‘necessary’ evolution of organized crime groups—a confirmation of this trend being the growing number of so called ‘mafia states’ around the world. Or, on the other hand, a criminal group may halt its evolution at the level of a crime syndicate. Probably, however, a sort of ‘a law of no return’ exists: if an organized crime group has developed links with elements of the political system, why should it give up this advantage? If this assumption is true, then those who argue that the mafia can evolve into a purely legal enterprize—and that this is why societies must ultimately learn to coexist with them—are either mistaken or lying.

Figure 1.1 The continuum of organized crime.

As regards the second question—how is it possible that organized crime may succeed in challenging even modern democracies?—the simplest way to answer this is to analyse organized crime groups as if they were ‘systems’ with their own authorities, regimes and structures (Armao 2000). And each of these systems, as such, interacts with its environment, consisting of other (sub) systems, such as the political, the juridical, the economical or the social (Allum 2000). What matters, from this perspective, is that the interaction among the systems is a necessity because they are not autonomous and their borders are not impermeable. The area of true interaction between criminals and, for example, politicians is a ‘grey zone’ which would be useful to analyse in scientific terms. The strength of a criminal group depends on its capacity to develop a network of relationships with members of other systems—entrepreneurs, politicians, and so on—which for convenience may be defined as the chance to obtain illicit advantages in defeating competitors (for example, both in the market, securing contracts, and in the political arena, buying votes) and attaining monopoly positions. This model of analysis fits mainly the peculiarities of mafia groups, which are therefore the most dangerous for democracy—which is why I will devote my analysis to this species.

‘Mafia’, as is universally known, is an Italian term; it identifies a criminal association specific to western Sicily, whose main characteristic is exactly its political nature (Pezzino 1994), in the Weberian sense: it aims to obtain a monopoly of physical force within a territory as a guarantee of its own system. The function of this monopoly is to accumulate resources to invest in illicit markets, but also to gain the consent necessary to infiltrate legitimate society. The term mafia, then, may be used to identify a peculiar model of criminal behaviour much more complex than that of ‘simple’ organized crime, and which equates, to give some examples, with Cosa Nostra, Camorra and ‘Ndrangheta, but also with the Japanese Yakuza and the Chinese Triads—not implying that all these organizations are identical, but that these and other criminal groups have similar structures and functions.

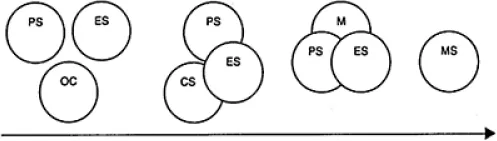

Figure 1.2 offers a dynamic representation of the relationships between different species of organized crime and political and economic systems. At the start, organized crime (OC) is clearly unconnected to the political system

Figure 1.2 The relationships between different species of organized crime and political and economic systems.

(PS) and to the economic system (ES); but as soon as a criminal group becomes more hierarchically structured, that is, it evolves into a crime syndicate (CS), it connects to the economic system (which is already ‘institutionally’ connected with the political system) and approaches the political system. Mafia (M) interacts with both political and economic systems, gaining a dominant position that may let it evolve into a mafia state (MS), in which the mafiosi also assume both the political leadership and the monopoly of the economic and financial resources of the State.

On the functions of mafia systems

What, then, is the definition of mafia? Mafia is an organization made up of different cells—clans—that are hierarchically structured, so that its authority (almost always protected by secrecy) is guaranteed yet at the same time its structure is loose enough to be able to adapt to different needs. Indeed, mafia pursues profits by means of monopolistic positions in illicit markets and makes instrumental use of licit markets, above all for covert activities and money-laundering. Finally, mafia gains its position by using violence as a specific, although not exclusive, means of acquiring political power.

Thus, mafia systems today appear to be much better equipped than the ‘old’ modern states in connecting the local with the global—the rediscovery of territoriality and ethnicity with the globalization of the economy. In other words, we must consider the mafia as one of the many different manifestations of modernity, which is functional to a particular way of conceiving of politics (both the authoritative distribution of power and the relationship between citizens and the state) and economics. The fact is that this way of conceiving of politics and economics is shared by a growing number of other groups operating in the legitimate world, and this is the reason why the mafia achieves increasing success.

To test this hypothesis, it is necessary to ‘travel’ through different levels of analysis, evaluating many variables. First, the mafia originated as an endogenous phenomenon only in certain states and in particular historical circumstances. It depends on the conditions in which the process of the monopolization of legitimate force by the central government occurs: instead of pursuing defeat of local authorities to centralize power resources, the State adopts a strategy of cooptation that allows these local authorities to survive together with their patronage (Tilly 1975). The mafia is thus the result of this ‘politics of patronage’ at a local level, whereby it came into being as the private army of a specific ‘landlord’. The problem with the mafia is not the absence of the State, but the will of the State to lower the costs of nation-building, subcontracting some roles and functions to these groups. This is the case, for example, of Italy after its unification in 1861, of Japan at the end of the Second World War and of Russia after the downfall of communism in 1989. As we have already argued, the control of a territory through violence, maybe of only a few districts in a city, is fundamental for a clan in order for it to progress in the accumulation of resources: money to invest in the much more profitable illicit markets (such as the drugs, arms and slave trades) and power to support the infiltration into legitimate society.

This may be the reason for the origin of the mafia, but to explain its expansion it is necessary to look at the evolution of the political systems involved and the monopolization processes which have taken place there. The evolution of the nation-state has been analysed by distinguishing between two main phases: the first—the formation of monopolies—of competition and conflict among a plurality of political actors that results, or should result, in the accumulation of power resources in the hands of a single authority, and the second during which the private power of the sovereign gradually becomes public by means of the distribution of resources to a growing number of groups (the nobility, the aristocracy, the bourgeoisie, for example) (Elias 1984–6). In some cases, it is clear that modern political systems have now entered a third phase, that of the ‘privatization of the public sphere’. This is not a simple rediscovery of previous phases: that of free competition or that of the authoritative distribution of resources by an absolute sovereign. Today states, some states, are capable of combining the arbitrary acts of authoritarian regimes with the universalism specific to democracies. They are still hierarchically structured, but this structure consists of different strata of clientages, in which the patron of a lower clientage may be a client in an upper clientage.

This is not to say that the patronage system and corruption equate with mafia, but that the mafia can take advantage of this way of conceiving of politics. It can offer its services to reinforce the traditional patron-client relationship through the use of violence: with the mediation of the boss, the client is no longer free to change patrons, and the patron has the certainty of not losing clients. But both patron and client become debtors of the boss. This is the logic which determines the success of the mafia in so many states: politicians do not settle for democratic elections, they do not want to be representatives but owners of their offices—though the same holds for all entrepreneurs who do not like free competition and prefer monopolistic positions. The mafia offers votes and gets rid of competition in all fields, but in turn it wants to manipulate politics or control public contracts. This is also the reason why, historically speaking, some mafia groups have only recently become states: it is much more convenient for criminal organizations to corrupt politicians, to collude with elements of the other system. But sometimes it happens that the State collapses, and in that case the search for a new power élite can favour groups such as the mafia, which hold both financial and violent resources. Political competition is reduced to a fight among clans within the State, but also among states, still seeking the control of illicit markets and the resources of the State.

This is certainly one of the possible interpretations of the recent events in almost all the ex-communist countries: the political transition to democracy has been overwhelmed by the need to organize the transition to capitalism; and this has been put in the hands of criminal organizations. New criminal-political leaderships try to manipulate public opinion and place additional value on ethnic identity and nationalist sentiments. But that these ideologies are purely instrumental is shown by these new leaderships’ conception of war; that is, by their way of improving politics through other means. The recent wars in the Balkans are a classic example: instead of mass armies in the field or true guerrilla warfare, the dominant aspect is the rediscovery of privateering: the replacement of professional armies belonging to the nation-state with criminal-mercenaries, who lack any moral code and claim their right to slaughter civilians and to rape women as pay for their services. This is the only method mafia systems can adopt to extend their use of violence.

Two alternating phases: entrenchment and expansion

These criminal groups named ‘mafia’—which arose within a small number of states around the world with very different traditions, but with the same strategy of monopolization—have already proved themselves capable of connecting the local dimension of territoriality with the global level of international financial markets. Before analysing in detail how the mafia has managed to combine both these aspects, it is worth noting that, paradoxically, it benefits from the increasing constraints imposed on na...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Contributors

- Foreword by David Beetham

- Series editor’s preface

- Acknowledgements

- Organized crime A threat to democracy?—Felia Allum and Renate Siebert

- PART I Definitions and diatribes

- PART II The ‘weakest link' The State under siege

- PART III Civil society held to ransom

- PART IV Organized crime and politics

- Index