- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Exporting American Architecture 1870-2000

About this book

The export of American architecture began in the nineteenth century as a disjointed set of personal adventures and commercial initiatives. It continues today alongside the transfer of other aspects of American life and culture to most regions of the world. Jeffrey Cody explains how, why and where American architects, planners, building contractors and other actors have marketed American architecture overseas. In so doing he provides a historical perspective on the diffusion of American building technologies, architectural standards, construction methods and planning paradigms. Using previously undocumented examples and illustrations, he shows how steel-frame manufacturers shipped their products abroad enabling the erection of American-style skyscrapers worldwide by 1900 and how this phase was followed by similar initiatives by companies manufacturing concrete components.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

ArchitectureSubtopic

Architecture Design

1 Exporting Steel-framed Skeletons of American Modernity

The exporting of American architecture began in the mid-nineteenth century as a disjointed set of personal adventures and commercial initiatives. Some of the adventurers were entrepreneurs selling either building components or prefabricated structures, such as slave structures, windmills and wharf buildings. Others were daring individualists with a flair for the unknown. Still others were building and planning consultants who were either lured abroad by new kinds of clients or propelled overseas by their U.S.-based headquarters. The scope of activities associated with this small and disparate cast of architectural exporters is easier to chart after 1876, when visitors from overseas marvelled at examples of American industrial technology displayed at the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition. Roughly two decades later, after the Chicago Columbian Exposition in 1893, both architectural episodes and building personalities received even greater notoriety abroad, particularly in Europe but also further afield (Lewis, 1997). However, it was not until the waning gasp of the nineteenth century that Americans awoke more fully to the possibilities of exporting their construction knowledge to commercial and cultural contexts so much further afield. ‘By 1900 the United States had successfully constructed one kind of empire – territorial across the continent – and was building another – economic as well as territorial – overseas’ (Twombly, 1995, p. 22).

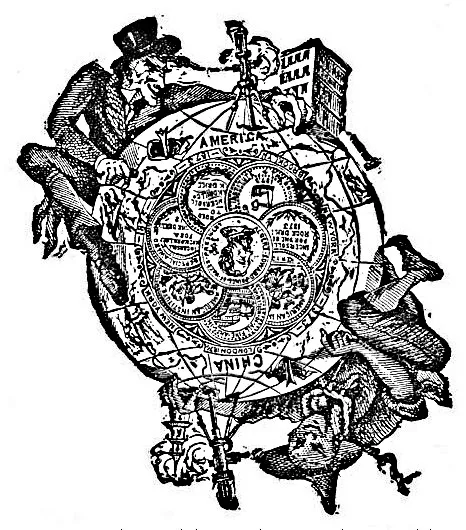

Figure 1.1. China and the U.S. clinging to the same globe. In this 1870s advertisement for an American-made rock drill, China is depicted by a man wearing a conical hat, next to his drill, with a pagoda in the background. The U.S. is caricatured as Uncle Sam beside a similar drill, with a four-storey office building nearby. The business connections between the two distant nations (implied here by a drill that could cut magically through the centre of the earth) became more of a reality in the late-nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. (Source: Chinese Scientific Magazine, 1877, 2(9), figure 9)

From a building material standpoint, these exporting activities were frequently related first to timber, iron and steel (a focus of attention in this first chapter), and then to concrete (scrutinized more fully in Chapter 2). Economically, these activities should be seen in the context of the 1893 depression, which provided an incentive for American entrepreneurs to engage in the broader range of foreign trade in order to produce a profit. In a political context, American exporting activities followed the U.S. annexation of Hawaii in 1898 and other major military victories secured by the United States in the Philippines and Cuba, when U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt and others began to demonstrate a staggering imperialistic stance. Some historians have seen these victories and the trade associated with them as the onset of a ‘new empire’ (LaFeber, 1963), and others as the trade associated with an American ‘informal empire’ (Hays, 1995, p. 208; Ricard, 1990). It was in this imperial context that American planners, architects and constructors in several allied professions began to ride on the political coat-tails created by those victories. They began to plan new communities, erect structures using U.S. technologies, fashion commercial and residential landscapes befitting American capitalistic enterprise and ship American-based building technologies to far-flung shores that most Americans could barely locate on a globe.

As will be shown more comprehensively in Chapter 2, by World War I these ventures began to coalesce into more rationalized processes and organizations and they began to reflect a particularly American brand of modernity. Other historians, who have previously probed the dynamics of what some have termed that ‘landscape of modernity’, have examined the relationships between pluralism and the American Century (Ward and Zunz, 1992, p. 4, and Zunz, 1998), between foreign politics and American pop culture (Wagnleitner and May, 2000), between Canadian and U.S. architectural practices in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century (Gournay 1998), or between high-rise construction and ‘américanisme’ (Cohen and Damisch, 1993 and Cohen, 1995). This scholarship is ‘part of a growing literature on the influence of American culture abroad’ (Kaplan and Pease, 1993; Pells, 1997; Appy, 2000; Wagnleitner and May, 2000, p. 4). However, despite this proliferating scholarship, what might be called the architectural/technological DNA of that modernity – the strands of construction-branded genes that comprise an architectural personality that many the world over recognized as ‘American’ in the early twentieth century – remains unclear.

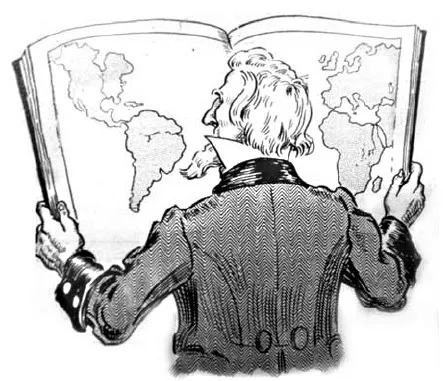

Figure 1.2. Uncle Sam gazing at a world atlas. As U.S. foreign trade swelled in the late-nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, many Americans engaged in that trade were compelled (for reasons of profit as well as curiosity) to learn more about the nations, cultures and peoples touched by U.S. corporate interests. (Source: Export American Industries, 1914, 13(4), p. 53)

These genes (primarily made of timber, iron, steel and concrete) were the progenitors of the architectural forms and spaces that designers, contractors and suppliers were marketing between 1876 and 1914, when business entrepreneurs, engineers, planners, contractors, and architects began to forge a first crucial portion of the foundation for the exporting of American architecture. Already by the 1860s American investors and U.S. federal institutions had begun snaking new commercial passages across that globe – Secretary Seward’s ‘folly’ of acquiring Alaska from Russia was in 1867, the same year that the U.S. acquired the Midway Islands in the Pacific. Soon thereafter Americans involved in many aspects of the building trades began to respond to the new opportunities implied by those ventures. Probably the best example of that trend was how one of the nineteenth century’s major construction-related swan songs – the Panama Canal – afforded American engineers and builders the possibility of demonstrating their skills in construction to a more global audience than had occurred in the years preceding the American Civil War (1860–1865). ‘By the 1890s the possibilities of foreign trade had come to excite the imagination of many American business and political leaders’ (Hays, 1995, p. 208). As many businesses began to feel the effects of the 1893 depression, the imagination of foreign trade was tied to the hope for greater profits. By the outbreak of World War I in 1914 – the same year that the Panama Canal became fully operational – American architectural expertise was becoming increasingly noteworthy, not only in Europe but also in regions under either formal or informal imperial reach. Americans associated with building – in all its forms – transmitted construction knowledge more rapidly than many now realize, from cities such as New York to Buenos Aires, or from Detroit to Shanghai. Information passed either through cables and published journals, or through conversation and actions in the field after the arrival of steamship and train travel. By the early years of the twentieth century, therefore, the first building blocks of a foundation for exporting American architectural know-how were in place. But how and when, precisely, did that transference occur and who or what was responsible for the actual laying of those blocks? What was the mortar binding them together? To analyse the dynamics and implications associated with exporting American architecture, it is critical to understand that foundation with greater clarity.

One way to achieve that clarity is to set a proper context in which the activities of crucial personalities and companies point to salient and meaningful trends. Before the 1880s those personalities and firms were few in number. Two American architects who exemplified the wandering, inquisitive nature of certain American architectural adventurers were Ithiel Town and Jacob Wrey Mould. During the late 1820s Town travelled in Europe on the kind of journey that countless other American architects have taken since, curious to see firsthand the architectural realities he had only read or heard about (Liscombe, 1991). A half-century later, after a career in New York, the ‘eccentric, ill-mannered’ Jacob Wrey Mould was employed by the railroad contractor Henry Meiggs to be the architect-in-chief of the Department of Public Works in Lima, Peru (Placzek, 1982, vol. 3, p. 247; Van Zanten, 1969). Town’s curiosity and Mould’s work for a government department presaged the activities of many American, construction-oriented professionals. Some of the key American designers of the later nineteenth century whose work began to be recognized overseas were even more wellknown in their own country than Town and Mould. For example, several scholars have shown how, in the 1880s, the work of architectural geniuses such as Henry Hobson Richardson began to attract the attention of European critics who marvelled at buildings such as Trinity Church in Boston and the Allegheny County Courthouse in Pittsburgh (Reinink, 1970; Tselos, 1970; Eaton, 1972). Australian architects were similarly impressed with Richardson’s Romanesque-style adaptations (Orth, 1975), and some Australian engineers in the 1880s were likewise so enthralled with the ways American builders were constructing viaducts to support railroads that they copied those solutions in the Australian outback (Crimes, 1991, p. 101). At the threshold of the twentieth century Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright followed Richardson’s lead in attracting the wide-eyed attention of many European observers. Moving beyond the scale of either the individual or the single work of architecture, recently some historians have begun to cast appropriate light on the powerful sway held by the American city itself, as well as the architects and planners associated with its dramatic rise, over many European urbanists in the late-nineteenth century and beyond ( Cohen and Damisch, 1993; Gournay, 1998 and 2002; Zevi, 1981; Koch, 1959).

Other architectural designers from the U.S. attracted attention not so much by their finished buildings as by their formative presence in European schools of architecture. For example, in the last quarter of the nineteenth century increasing numbers of U.S. architectural students followed the pioneering lead of Richard Morris Hunt to the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, the mecca of architectural education, where they began to interact professionally with largely European peers (Baker, 1980). These examples were meaningful not only because of what they implied for the development of American architecture domestically, but also because they set key precedents for U.S. architects commanding stronger respect among their European counterparts.

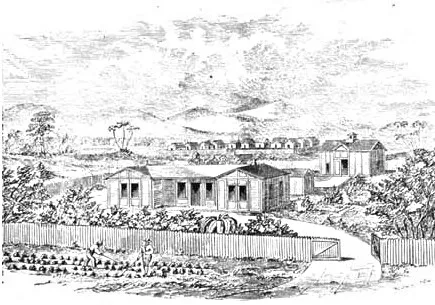

Other precedents, although much less well known to later observers because their existence was often only documented in either newspapers or trade journals, were also fundamentally important in laying the foundation for American architectural exportation. For example, some of the earliest cases of that exportation were related to slavery, seen in how West Indies plantation owners purchased designs from Boston or New York as early as the 1860s to house slaves (Skillings and Flint, 1861) (see figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3. American-made plantation buildings shipped to the West Indies in the 1860s. (Source: D.N. Skillings & D.B. Flint, 1861, Illustrated Catalogue of Portable and SectionalBuildings. Boston: the authors)

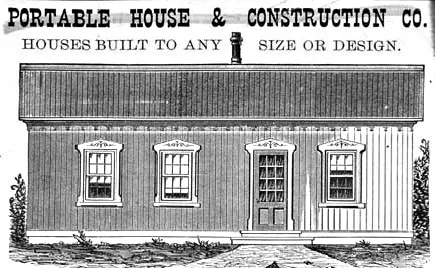

This example of exporting slave structures resonates with what the historian John Blair has learned about how some of the earliest exports of American popular culture – Jim Crow variety shows and Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West show were similarly rooted in racism (Blair, 2000, p. 17). Many of the designs for slave dwellings were for onestorey, rectilinear structures whose uncomplicated joinery made them easy to erect, probably by those very slaves who lived in them. Flexibility, economy and ease of construction were significant factors that attracted potential buyers. Such was the case, for instance, of the wooden but ‘warm as brick houses built to any size or design’ that the Ayer’s Portable House and Construction Company shipped abroad from Chicago in 1879 (figure 1.4).

Figure 1.4. Portable timber-frame house sold to foreign clients in the late 1870s by the Ayer Company of Chicago. By the turn of the twentieth century, other kinds of prefabricated buildings followed the precedent set by these timber structures in being shipped as a kit of parts that could be assembled upon delivery. (Source: AmericanExporter, 1879, 3(6), p. 35)

Relative to European exports, which were sometimes elaborate kits in parts, the first American examples of exporting ‘portable buildings’ were small-scale operations initiated by timber merchants who specialized in satisfying clients’ desires for cheap, quickly-transported, low-rise, boxy spaces where either slaves or others could reside, or where a variety of simple functions could be performed (Lewis, 1993). In the early twentieth century, several American companies were still exporting ‘knockeddown’ houses; one of the most significant was the Aladdin Company (figure 1.5) (American Exporter, 1913, 73(7), p. 135; American Exporter, 1914, 74(1), p. 119). Larger wood-framed ‘portable houses’ were also being shipped abroad, particularly to Central and South America, by the turn of the century (American Mail and Export Journal, 1894, 21(9...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Exporting Steel-framed Skeletons of American Modernity

- 2 From the Steel Frame to Concrete: Foundations for a System of Contracting Abroad, 1900–c.1920

- 3 American Builders Abroad at a Fork in the Road: Adjust or Go Home, 1918–1930

- 4 Exporting the American City as a Paradigm for Progress, 1920–1945

- 5 Architectural Tools of War and Peace, 1945–1975

- 6 The American Century’s Last Quarter: Exporting Images and Technologies with a Vengeance, 1975–2000

- Bibliography

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Exporting American Architecture 1870-2000 by Jeffrey W. Cody in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture Design. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.