Chapter One

Introduction

The task of the historian is first to recognize the seeds and to indicate—across all layers of debris—the continuity of development.1

People in the Roman world turned to the gods for “salvation” (sôtêria) from a range of destructive forces, known and unknown, mundane and supernatural. With just a little prodding, a few words, and a humble sacrifice, the gods would grant the ephemeral quality of sôtêria. Salvation did not last a lifetime, much less for eternity, for this salvation pertained to specific moments of anxiety, sickness, disorder, and dislocation. Often people asked the gods for the salvation of themselves and their families. Just as often they asked for the salvation of others, usually superiors to whom they were obligated, including patrons and especially the ultimate patron of the Roman world, the emperor. Herodian, a historian from Syria and a Roman official writing in the early third century A.D., mentions two instances. In 187, the emperor Commodus, the cruel son of Marcus Aurelius, survived yet another conspiracy. The official line must have stressed the gods’ role in the unraveling of the plot. Always wise in matters of state, the gods had saved their beloved Commodus, for after the conspirators had been executed, the emperor sacrificed to the goddess Hilaritas, whose festival day it happened to be, and voted a public thanksgiving. Dispelling any lingering doubt about the stability of the emperor’s imperium, Commodus confidently joined the procession of the goddess. With a collective sigh of relief, the people then celebrated Commodus’ salvation (sôtêria).2 Naturally, many were also eager to negotiate their own salvation, for which, once received, they would offer sacrifice and thanks to the gods. In a suspiciously dramatic narrative, Herodian records that the emperor Caracalla, after killing his brother and co-emperor Geta in the arms of their mother, rushed from the scene, shouting out that he had just been “saved” (sôthênai) from his brother’s treachery. He headed straight to the Praetorian Camp, where he entered the shrine of the Roman standards, prostrated himself before the images, and gave thanks and sacrificed for his own salvation (hômologei te charistêria ethue te sôtêria).3

In both accounts, Herodian is not interested in religion for its own sake. His intent is rather to show how bad emperors cynically used religious rituals—specifically the offering of thanks to the gods for sôtêria—to dupe the masses and mask political murder. For our purposes, the particular circumstances are not as important as the off-handed mention of the practice itself, specifically the emperor’s duty to the gods to perform sacrifice for his own salvation, and the participation of the people of Rome in offering thanks for the salvation of the emperor during a public festival. In this way, the Roman people affirmed that the emperor had been “saved” by the gods and also registered their abiding loyalty to the current emperor. For Herodian and his audience, all of this was perfunctory, the humdrum of ceremonial life at the capital. By the third century, such rituals were indeed practiced not only in Rome but also in the far corners of the Roman world. Herodian’s audience was of course aware of this fact and must have been sensitive to the outrageousness of the abuse of standard religious rituals.

This book is about the means by which a range of individuals and collectives secured salvation, their motivations, and those who were intended to receive the salutary benefits from the gods. Quite often, the means took the form of inscriptions that commemorated both the desire for salvation and its fulfillment through the formula hyper sôtêrias or pro salute, in Greek and Latin respectively, after which was normally written the name of the person who was to be, or had been, saved: “For the salvation of so and so.” What follows is a case study of the use of this epigraphic formula in the Near East. In this region, the formula hyper sôtêrias was in use for years before Rome arrived in the first century B.C. and absorbed the region in its vast, polyglot empire, and its use lasted until the middle of the eighth century A.D., when Greek was dying out as a spoken language and the region was ruled not from Rome, Constantinople, or Damascus but from Baghdad. Indeed, the formula is so common that editors, when they are confronted with yet another example of this type, shrug it off as a pious “ejaculation,” devoid of true religious sentiment or historical significance.4 Because of this attitude, there has been no attempt to understand the notable persistence of this formula and others like it over nearly a millennium.

Since Roman provincial boundaries shifted over the centuries, sometimes in ways that we cannot fully follow in detail, the geographical focus will be the modern states of Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, and Israel, rather than the equivalent Roman and early Byzantine provinces of Syria, Phoenicia, Palestine, and Mesopotamia.5 Occasionally it will be necessary to journey outside these modern borders, to gather, for example, a rare inscription from the rafters of the chapel at Mt. Sinai, deep in the wastes of the Sinai Peninsula. During the 900 years that the formula was in use, from the first century B.C. to the eighth century A.D., it was used more or less constantly in the religious koinê of town, village, and countryside, among pagans, Christians, and Jews. This regional focus and chronological limit are ideal for a study of this type for two reasons. First of all, in this region, thousands of inscriptions have come to light, revealing a society that included a surprising variety of local cultures, all living with, and adapting to, the Roman military and administrative apparatus and, later, the rise of Christianity and the triumph of Islam. Second, despite the availability of evidence, the inscriptions from this region have received relatively little attention compared to those from either Asia Minor or Egypt.6

In the Greek world, dedications for sôtêria originated as a form of payment to the gods for a vow made during periods of danger and uncertainty. Thus sôtêria came to be part of the language used to express thanksgiving to the gods for salvation received or anticipated, tying the dedicator to the divine in a personal relationship.7 Unlike in other parts of the empire, in the Near East this mentality was not restricted to a Greek cultural milieu. There were also equivalents in the local languages that were in use among Babylonian elites in the first millennium B.C., revealing analogous religious mentalities that existed in the region for several centuries before the establishment of the Hellenistic kingdoms and the coming of Rome. Kings, for example, prayed to gods for their own “life” (namti) in exchange for the dedication of temples, wells, and fortresses.8 Imperial subjects also made offerings for the king and queen’s “life.” In one case, a temple magician made such a dedication on behalf of the queen.9 And some asked the gods for their own and their family’s “life.”10 A similar expression is found in Old Aramaic inscriptions from Iran (?) that date to the seventh century B.C.: CL HYY, “for life.” This Aramaic formula continued to be used virtually unchanged until the third century A.D. in Petra, Palmyra, Hatra, and elsewhere.11

Although native formulaic equivalents for sôtêria existed in a variety of languages, I would not want to posit a direct Semitic influence on Greek religious practice, since votive offerings to gods for salvation’s sake must have developed independently in the Near East and the Greek world.12 Still, it is plausible to suggest that the Greek idiom, attested from at least the second century B.C., found fertile ground in the cultures of the Near East, since there was already an epigraphic habit of this sort. Thereafter the Greek formula fused with these native traditions and joined the Aramaic formula in constituting part of the region’s religious imagination.13 It is important to keep these deep-seated traditions in mind as we consider the evidence from the Roman period. When people in the Near East began to make dedications for salvation’s sake in Greek and Latin, they were building upon a firmly established, older tradition, of which they may or may not have been fully aware. Moreover, this tradition and the mentality behind it might explain the density of dedications for salvation’s sake in the Near East, relative to the surrounding regions.

THE NATURE OF THE EVIDENCE

In the Near East, dedications for salvation’s sake in Greek and Latin spanned the transition from the pre-Roman to the Roman period and from the Roman to the Christian period. There are two types of dedications: those made for the salvation of the emperor, and those made for personal salvation. The number and variety of sôtêria dedications for the salvation of emperors or personal salvation recorded in the Near East is substantial, more than 400 inscriptions. Including those with dubious readings, the total number of the dedications for the salvation of emperors is 191, virtually all of them in Greek. The dedications refer to twenty-four emperors, from Tiberius (A.D. 14–37) to Justinian (A.D. 527–65), over a 500-year period and were commissioned by individuals widely separated in space, from the plush steppe of northern Syria to the inhospitable mountains of the Sinai peninsula. However, nearly all of these dedications can be dated to the second and third centuries, the boom period of epigraphic production throughout the empire. The number for personal salvation is 221; these span a similar expanse of territory but a much longer time period. In my sample, the first dedication for personal salvation dates to 69 B.C. and the last to A.D. 762. Not included in this tally, however, are inscriptions that contain words related to sôtêria, such as those that thank the gods for “having been saved” (sôtheis), not an uncommon formulation;14 nor dedications in Aramaic that ask for the similar quality of “life.”

“For the Salvation of the Emperor”

Over two hundred individuals, some acting as groups, made dedications for the salvation of the emperor through the formula

or its Latin equivalent

pro salute. These dedications were set in a variety of contexts. In temple precincts, the pious visitor might see dedications for the salvation of emperors on stoas, statue bases, and altars. As he entered the temple, he might also see such dedications on the walls flanking the entrance or on the massive lintel that framed the door. Walking through a well-off town or village, a visitor might notice that public buildings, such as gates, arches, nymphaea, theaters, and baths, were dedicated for the salvation of emperors. In the camp, a soldier might see dedications for the salvation of emperors on the walls of military structures, such as

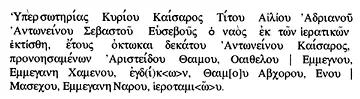

principia and fortresses. Public works projects, such as aqueducts, bridges, and roads, also bore such inscriptions. Take as an example this dedication from a temple at Hebran, a village in southern Syria:

For the salvation of Lord Caesar Titus Aelius Hadrianus Antoninus Augustus Pius, the temple was built from the sacred (funds), in the eighteenth year of Antoninus Caesar, the commissioners of the construction being Aristeidos, son of Thaimos, Uaithelos, son of Emmegnos, Emmeganê, son of Chamenos, ekdikoi, Thaimos, son of Abchoros, Enos, son of Masechos, Emmeganê, son of Naros, templetreasurers. 15

It was A.D. 155 and the emperor was Antoninus Pius. The dedicators are otherwise unknown and the village insignificant. Nevertheless, this inscription, and the hundreds like it from throughout the empire, is a local affirmation of the imperial ideology.

From the first to the fourth century, the rate at which inscriptions for the salvation of the emperor were produced mirrors the “epigraphic habit” of the Roman empire as a whole (see Table 1 and Table 6).16 After a scattering of dedications in the first century, a sharp rise occurred during the reign of Trajan and continued throughout the second century with the exception of a significant drop during the reign of Commodus. The cluster of epigraphic activity during the Golden Age of Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, and Marcus Aurelius is hardly surprising. This was a period of explosive urban development in the Near East, despite intermittent warfare, rebellion, and a major plague that struck in the latter half of the second century.17 After the death of Septimius Severus, the dedications continued, if at drastically lower rates, until the middle of the fourth century. But the epigraphic habit alone was not the only factor that fueled the production of these inscriptions. From Trajan on, the legend SALUS AUG appeared on coins consistently until the fourth century.18 The “salvation of the emperor” had thus become an official slogan of sorts, coinciding, no doubt, with the increased production of dedications for the salvation of emperors.

In addition to sôtêria, the dedications contain key words that reflect different aspects of Roman imperial ideology. These dedications ask for the salvation and victory (nikê or victoria) of the emperor; salvation, victory, and safety (diamonê or incolumitas); salvation, fortune (tychê), and safety; salvation, safety, and concord (harmonia); salvation and concord; salvation, concord, and prosperity (eudaimonia); salvation and health (hygeia); and salvation and return (epanodos). Some of these formulas did not last long. For example, dedications for salvation and health flared up only in connection with the construction of an aqueduct in southern Syria under Trajan. Some arose relatively late: dedications for the salvation and safety of the emperor began to appear in the latter half of the second century and were especially prominent in the early half of the third century. And some tended to concentrate regionally: most of the dedications for the salvation and victory of the emperor were made in Syria (encompassing parts of Roman Syria and Arabia), beginning during the joint reign of Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus, at a time when Rome was at war with the Parthian king of kings, and lasting until the fourth century, when the final dedications fo...