eBook - ePub

Maori

About this book

This descriptive grammar provides a uniquely comprehensive description of Maori, the East Polynesian language of the indigenous people of New Zealand. Today, the language is under threat and it seems likely that the Maori of the future will differ quite considerably from the Maori of the past.

Winifred Bauer offers a wide-ranging and detailed description of the structure of the language, covering syntax, morphology and phonology. Based upon narrative texts and data elicited from older native-speaking consultants and illustrated with a wealth of examples the book will be of interest to both linguistic theoreticians and descriptive linguists, including language typologists.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Syntax

1.1 GENERAL

1.1.1 Sentence types

1.1.1.1 Direct speech and indirect speech

The preferred method of reporting speech is direct quotation. The commonest introductory verb is mea ‘say’, though others such as karanga ‘call’ can also occur, and more elaborate formulae are found in some styles, eg. Ko te kupu a Tutaanekai ki a Hinemoa ‘Tutanekai's words to Hinemoa were…’. The introductory phrase, of the general form ‘X said/spoke’ precedes the quoted words. The orthographic convention varies: sometimes the introductory phrase is treated as an independent sentence, and sometimes not. In speech, it is always treated as a separate sentence, receiving sentence final intonation on the final phrase (see 3.3.4.1–2). The following extract from the tale of Hinemoa will illustrate these points.

| (1) | Ka karanga atu a Hinemoa, ki taua T/A call away pers Hinemoa to det aph taurekareka nei, anoo he reo tane. Moo wai slave proxI as a voice man intgen who too wai? Ka mea mai te taurekareka raa. sggenIIsg water T/A say hither the slave dist Moo Tutaanekai. Naa, ka mea atu a intgen Tutanekai then T/A say away pers Hinemoa, Homai ki ahau. Hinemoa give to Isg ‘Hinemoa called out to this slave in a man's voice. “Who is your water for?” That slave responded/spoke back. “For Tutanekai.” Then Hinemoa spoke. “Give it to me.”’(H, 8) |

Indirect speech also occurs. There are many introductory verbs, eg. ui ‘ask’, paatai ‘ask’, whakahoki ‘reply’, kii ‘say’, mea ‘say’, whakautu ‘respond’. In indirect speech, the pronouns are changed to accord with the introductory clause (which is always part of the same sentence), but tenses are not changed. The following examples illustrate. The corresponding direct speech is given as (b) for comparison.

| (2a) | Ka whakahoki a Tamahae i te hii ika a T/A reply pers Tamahae T/A catch fish pers ia IIIsg ‘Tamahae replied that he had been fishing’ |

| (2b) | I te hii ika au T/A catch fish Isg ‘I've been fishing’ |

| (3a) | Ka paatai a Hata kei whea ngaa ika T/A ask pers Hata at(pres) where the(pl) fish ‘Hata asked where the fish were’. |

| (3b) | Kei whea ngaa ika? at(pres) where the(pl) fish ‘Where are the fish?’ |

The word order normal for Maori (basically VSO) is used in both the introductory and the quoted sentences, whether the quote is direct or indirect.

1.1.1.2 Interrogative sentences

There are three basic types of question that can be distinguished in Maori, yes-no questions (1.1.1.2.1), question-word questions (1.1.1.2.2), and echo-questions (1.1.1.2.3). The first and last of these are distinguished from declaratives principally by intonation. However, intonation is subject to considerable regional variation. It also appears to vary with sex. The intonation patterns outlined here are those of a male Ngati Porou speaker (ie. East Coast, North Island).

1.1.1.2.1 Yes-no questions

The norm for questions of this kind for older speakers is raised pitch throughout. However, many younger speakers fail to produce raised pitch (indeed some report that they find it embarrassing to do so), and they tend to rely on other means to mark these forms as questions. Yes-no questions do not differ from declaratives in word order.

1.1.1.2.1.1 Neutral yes-no questions

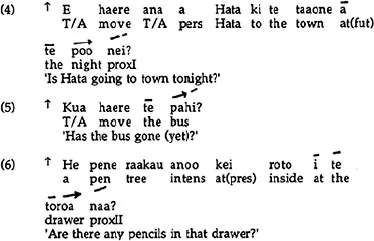

Questions of this type are marked by raised pitch throughout the utterance (indicated by the vertical arrow preceding), and a high rise on the final phrase. Word order is identical to that of declaratives, eg.

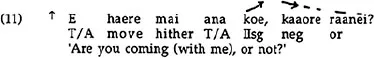

To underline the fact that these are questions, it is possible to add raanei ‘or’ following the verb in (4) and (5) (ie. after ana and haere respectively), and following anoo in (6) which is non-verbal. This use of raanei is almost certainly increasing, since younger speakers rely on raanei and final rising pitch to mark such forms as questions.

The intonation of these questions described above presumes unmarked focus. If some marked constituent is in focus (eg. Hata in (4)), that constituent receives a fall-rise, but the same general outline is followed for the intonation of the question as a whole. However, for constituents other than the subject in focus, it is more likely that a different question will be asked, eg. to focus on the location:

| (4a) | Hei/Ko te taaone a Hata i te poo nei? at(fut) the town pers Hata at the night proxI ‘Will Hata be in town tonight?’ |

If the time adverbial in (4) is in focus, it is likely to be fronted:

| (4b) | A te poo nei, ka haere a Hata ki te at(fut) the night proxI T/A move pers Hata to the taaone? town ‘Is Hata going to town tonight?’ |

1.1.1.2.1.2 Leading questions

These have the particle nee sentence finally, in a separate tone group. Otherwise, they have declarative word order and intonation contours.

1.1.1.2.1.2.1 Expecting the answer ‘yes’

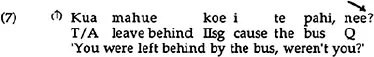

In these questions, nee receives falling intonation. Raised pitch throughout often occurs, but is not always used, even by older speakers.

| (8) | Ko tana whare te mea whero, nee? eq sggenIIIsg house the thing red Q ‘His house is the red one, isn't it?’ |

1.1.1.2.1.2.2 Expecting the answer ‘no’

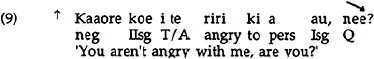

In such questions nee usually receives falling intonation. However, a rise on nee sometimes occurs, perhaps when the possibility of contradiction is allowed for. While falling intonation is probably normal for the phrase preceding nee, various modifications occur, particularly if the speaker is pleading. The commonest modification appears to be a fall-rise. Whether this is just a sandhi effect I am unsure. The fall on nee often appears to start higher when the answer ‘no’ rather than ‘yes’ is expected.

| (10) | Kaaore i maka·ia atu e koe te reta, nee? not T/A throw·pass. away by IIsg the letter Q ‘You didn't throw away the letter, did you?’ |

1.1.1.2.1.3 Alternative questions

These consist of a positive statement first, with rising intonation on the final phrase, followed by a phrase of the general form ‘negative word+ raanei’, with falling intonation. The negator used is that appropriate to the full negation of the declarative (see 1.4).

| (12) | He tangata kai paipa koe, eehara raanei? cls man eat pipe IIsg neg or ‘Are you a smoker, or not?’ |

1.1.1.2.2 Question-word questions

These are marked by a rise on the question word, and a fall sentence-finally. However, if the question-word falls in the final phrase, either falling or rising intonation may occur sentence finally. I have been unable to discover any distinction dependent on this choice. Many such questions, but not all, also involve changes in sentence structure. These are dependent on the grammatical function of the constituent in which the question-word occurs.

1.1.1.2.2.1 Questioning sentence elements

1.1.1.2.2.1.1 Main clause constituents that can be questioned

Any constituent of the main clause can be questioned, but the c...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- MAORI

- Descriptive Grammars

- Titlte Page

- Copyright

- EDITORIAL STATEMENT

- CONTENTS

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Map

- Abbreviations

- Glossary

- 1. SYNTAX

- 2 MORPHOLOGY

- 3 PHONOLOGY

- 4 IDEOPHONES AND INTERJECTIONS

- 5 LEXICON

- Textual sources

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Maori by Winifred Bauer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.