1

Understanding Human Error

Marilyn Sue Bogner

Institute for the Study of Human Error, LLC

It is one thing to show a man that he is in an error, and another to put him in possession of truth.

—John Locke (1632–1704)

An Essay Concerning Human Understanding

In all aspects of life, human error has been the attributed cause of faulty products and accidents with consequences ranging from inconvenience, through loss of property and resources, to death. The media informs the public of disasters caused by human error. Among those disasters are the collapse of crowded walkways in the Kansas City Hyatt Regency Hotel (114 people killed and 200 injured) due to a deviation in the structural design and unanticipated use (Petroski, 1992); the sinking of the ferry Herald of Free Enterprise (188 crew and passengers lost) because the bow doors through which cars entered were not closed, allowing the ocean to enter the hold (Buck, 1989), and the emissions from the Chernobyl nuclear power plant failure that were carried by the winds to affect distant communities. People express interest and concern about those incidents as well as other construction, transportation, and industrial disasters reported as caused by human error. There is no hue and cry, however, for something to be done about them. After all, those disasters happened to other people in other places—they didn’t affect us. Then came the bombshell of a report on human error that affects everyone.

The population of the United States was, shocked, stunned, and outraged by the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM) report, To Err Is Human, which cited human error in medicine as the cause of death for tens of thousands of individuals who sought the curative powers of hospitalized care (Kohn, Corrigan, & Donaldson, 1999). Close on the heels of that report was one from the United Kingdom (U.K.) indicating that in National Health Service hospitals medical errors harm (inflict injury as well as death to) 10% of admissions, or a rate in excess of 850,000 annually (Department of Health, 2000). Although the U.K. report received a pittance of the media coverage of the IOM report, it gave credence to the number of deaths attributed to human error by the IOM.

Not only did the U.K. report confirm that medical error is a problem, by including injuries as well as deaths in the reported number, it also expanded the magnitude of the problem. The numbers cited in the IOM report were of deaths; including error-related injuries would increase the numbers considerably. Although it has not been assessed, there is no reason to doubt that harm related to errors also occurs in outpatient care, which increases the magnitude of the problem even more. The problem would be even greater if, in addition to serious injuries and death, the number of patients who require additional treatment because of adverse outcomes from error were included. Thus, medical error or, more broadly stated to include all forms of care, health care error is a problem— a problem with profound financial and social implications for the nation at large as well as ramifications for the people directly involved.

To address the problem of medical error, the IOM report recommended a mandatory adverse event reporting program that requires health care providers, particularly physicians, to report their errors for the purpose of accountability. That recommendation reflects the assumption about the nature of error expressed in the title of the IOM report, an attitude that is pervasive throughout society, that humans, including health care providers, are innately error-prone. Such an attitude is very powerful because it determines the focus of efforts to reduce the likelihood of error. If the focus is accurate, then efforts to address error are effective; however, if the focus is inappropriate, then efforts to address error are misdirected and the problem persists. To address adverse outcomes through appropriately directed efforts, it is necessary to understand human error. The first step in understanding human error is to define it.

DEFINING ERROR

Typically an error is described in terms of what happened, the adverse outcome such as amputating a healthy leg, making an inaccurate diagnosis, omitting a dose of medication, or more generally, deviating from the standard of care. The commonality in those examples is that each involves an act, an action by a care provider that affects the patient. This can be an act of commission, an overt activity, or an act of omission, the absence of an activity. In addition, an error may be rule-based, skill-based, or knowledge-based (Rasmussen, 1990a). Errors can be slips, lapses, mistakes, and violations; they can occur at the sharp end, immediate to, and at the blunt end, distant from, the point of care as well as be latent (Reason, 1990). Although the variety of descriptions indicates that errors have differing characteristics, they all describe acts, behaviors.

ERROR AS BEHAVIOR

Considering error as behavior is important to understanding human error. It bridges the real world of health care errors with the nearly two centuries of insights from the academic discipline that studies human behavior, psychology, as well as the many centuries of thought on the human condition by psychology’s parent, philosophy. Error as behavior also is the bridge to insights expressed in plays, novels, biographies, and other writings by astute observers of human endeavors—insights that can aide in understanding human error as discussed in the last chapter of this book.

Theory and research findings describe human behavior as the interaction of the person and the environment. The extent to which a person influences the environment and is influenced by it varies by school of thought; nonetheless, the insight provided for understanding error is that behavior is a function not of a person in isolation, but of the person interacting with the environment (Lewin, 1936/1966). This expands the understanding of error from the simple concept of people committing errors driven by their innate error-proneness, to the complexity of people interacting with their vast and varied environments. To appreciate the importance of this expansion, let us consider what is involved in the delivery of health care.

Health Care Delivery

Human error in health care typically is considered as just that, an error committed by a person, an error-prone human. This concept is reflected in programs that require care providers to report their errors. An error reported as an adverse outcome is a solitary data point. An outcome, however, is not a disembodied datum; an outcome doesn’t happen spontaneously. Rather, an outcome is the result of a treatment administered by the provider such as a medical procedure, a diagnosis, a test, counseling—an error involves a means of providing care. An error happens to a person, the care recipient—an error involves a patient. Thus, what began as a seemingly simple concept of error in terms of only an adverse outcome has become a complex concept involving the provider, the means of providing care, and the care recipient. Health care is not static; for an outcome to occur some activity must take place. That activity involves interactions among the three entities, which increases the complexity of the concept of error.

Even though a health care provider interacts with the means of providing care and with the patient, little attention is paid to possible implications for provider performance from the means of providing care and even less to implications from the care recipient. There are performance implications, however; each of these entities is a system of interacting and interdependent characteristics that affect and are affected by characteristics of the others (Bogner, 1998). The health of a care provider influences how a technologically sophisticated means of providing care is applied to a morbidly obese patient; changes in any of the entities can cause changes in the others. Such interrelated and interdependent interactions define a system; hence, the three systems involved in the delivery of health care become subsystems of the basic care providing system (Bogner, 1998).

Because the interaction of the characteristics of the members of the basic unit of health care delivery define a system, understanding provider error necessarily involves the consideration of error in terms of the members of that system: the means of providing care and the care recipient. The discussion to this point has addressed health care delivery devoid of environmental context; yet it does occur in a context.

Environmental Context

In no other human endeavor do a wider variety of people perform tasks in more diverse conditions than in health care. Health care is delivered by professionals skilled in a wide range of specialties, athletic trainers, medics, and lay persons ranging from the elderly to children; health care is delivered in hospitals, on sports fields, in space modules, on battlefields, and in the work place. Errors can and do occur in all of these contexts. Although the IOM report (Kohn, Corrigan, & Donaldson, 1999) and that regarding the National Health Service in the U.K. (Department of Health, 2000) address error by health care professionals in hospital settings, consideration of other environmental contexts of health care— contexts in which errors and adverse outcomes occur, can provide broadly applicable insights. The complexity of the greater environment even as it applies to hospitals presents a challenge for understanding error; the magnitude of the problem of adverse health care outcomes demands that the challenge be met. Assistance in meeting that challenge comes from industry.

LESSONS LEARNED FROM INDUSTRY

Factors have been identified that affect the performance of a person and lead to error in industries such as nuclear power and manufacturing (Moray, 1994; Rasmussen, 1982, 1994; Senders & Moray, 1991). Admittedly, health care is not the same as the activities of those industries, however, to the extent that such evidence-based factors may contribute to error in general, considering them with respect to health care could lead to insights vital to understanding human error whether it occurs in industry or health care.

Factors identified as contributing to errors in specific industries when extrapolated from those industries can be considered as factors in the general environmental context of a task that contribute to error. Those factors are clustered into five categories representing aspects of the context of care (Bogner, 2000).

Context of Care

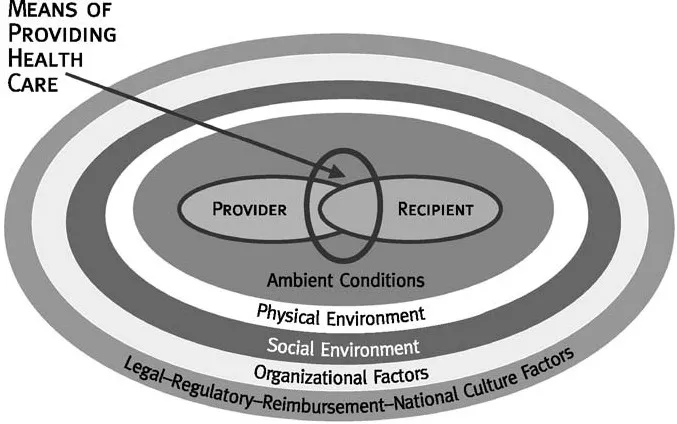

The factors in each of the categories of the aspects of the context of care are interrelated; they affect and are affected by the other factors in the specific category. By being interrelated, the factors in each category define the category as a system. These categories of factors are the five systems of the context of care: ambient conditions, physical environment, social environment, organizational factors, and the overarching legal-regulatory-reimbursement-national culture factors represented as the concentric circles in Fig. 1.1. The five systems are interrelated and interdependent and as such define the context of care as a system.

The three systems of the basic care-providing system, the provider, means of providing care, and the care recipient, are embedded in the system of the context of care. Those eight systems of factors are interrelated and interdependent and define the overall context of error as a system. In keeping with the food analogies of error as Swiss cheese (Reason, 1990), and an onion (Moray, 1994), this systems approach to error (Bogner, 2000) is analogous to an artichoke. The leaves of the artichoke are the concentric circles in Fig. 1.1 representing the five contextual systems, with the system of overarching factors being the external leaves and each system of characteristics, the organizational factors, social environment, physical environment, and ambient conditions as concentric rings of leaves surrounding the heart of the artichoke, the basic care providing system.

The concept of the context of error as a system of subsystems is important in considering the impact of factors on provider performance, hence error. Changes in any of the systems of the context of error produce a reverse ripple. Rather than rippling out from the point of impact, as when the surface of a pond is disturbed by a stone, the impact of a change in any system ripples inward. That is, systems within the circumference of the system with the change are influenced by the change (see Fig. 1.1). For example, changes in the physical environment affect the social environment, ambient conditions, and ultimately the members of the basic care providing system, the care provider, means of providing care, and the patient with little if any impact on the organization and none on the overarching societal level factors.

FIG. 1.1. The systems approach artichoke model of error.

The greatest impact occurs from a change in the overarching system of legal-regulatory-reimbursement-national culture factors. A change in reimbursement policies that reduces the amount of reimbursement for certain procedures alters the funds available to the organization which necessitates reductions such as the number and educational level of the staff; this affects communication among the staff and with patients’ families, building maintenance, purchasing of equipment, and patients who present at more advanced stages of illness—all of which affect the care provider.

Because of the reverse ripple, the origin of a factor that induces error may be other than where the factor impacts the provider, so efforts to change those factors may be applied inappropriately and doomed to failure. For example, a resident’s excessive workload although emanating from the organization, the hospital, may be the result of funding limited by reimbursement policies. Directing the hospital to reduce the workload could be ineffective or even counter- productive; efforts would be directed more appropriately to those governing reimbursement policies.

In terms of the artichoke model, exerting strong pressure on a leaf in one of the circles of leaves representing systems results in pressure which changes the condition of circles of leaves, the systems, between the ring where the leaf is pressured and the heart of the artichoke. The basic system of care, by being central to the context of care, is affected by a change in any system; the heart of the artichoke is affected by what happens to any of the leaves.

WHY BLAME THE PROVIDER?

The meaning of a sentence is questioned when it is taken out of context, contexts are constructed with soft light and music to evoke certain behaviors, and efforts are made to construct the social context of a society from its archaeological artifacts. Yet, the context in which a health care error occurs typically is not considered as playing a role in the error; the care provider is blamed for the error. It is acknowledged that care providers commit errors; however, blame provides no insights as to why the error occurred so that it may be prevented, no aid in understanding human error. Thus the question, why blame the provider?

In addressing an event such as an error, people tend to seek a reasonable explanation for it, and once such an explanat...