![]()

1

Charles Melville and Persian Pembroke

Michael Kuczynski

From the postern gate of Wellington College an avenue of Sequoiadendra gigantea once stretched to the edge of the park at Stratfield Saye, the Duke’s house five miles away, in whose memory the school had been founded after his death in 1852. By the late 1960s, however, the A33 and the fungal spread of military establishments around Sandhurst had left little more than a hundred yards of the magnificent Wellingtonias beyond which modern urban sprawl beckoned, luckily all but concealing the rich chalk-stream fishing of the Loddon, that occasionally lovely tributary of the Thames which runs from Basingstoke to the rowing at Wargrave. Such is the place that Charles Melville left in the agitated summer of 1968, to set out on an antipodean gap year and then to arrive, at the start of October 1969, as an undergraduate equipped with a striking dark mane, makeshift easel and oils, and the settled purpose of reading Arabic and Persian, at Pembroke College, Cambridge. This note intends three aperçus: first, what Melville did and suffered as an undergraduate; then something of the subject that he came to read at Cambridge, in particular, at Pembroke; and, last, something on him as a colleague and commensalis.

I

The Aristotelian part is properly brief. Arthur Arberry, who had been at Pembroke off and on since 1923, latterly as Sir Thomas Adams’s Professor of Arabic, died at the start of October 1969, on the day Melville came up. Arberry, of whom a little more anon, had just published his last translation, of the Apologia of ‘Ayn al-Qudat, the twelfth-century polymath from Hamadan martyred at age 33. Pembroke was tentatively emerging from one of the chrysalis stages of its various lifecycles, and had just elected its first two ‘external’ research fellows. Oddly enough the college, and in particular Melville’s tutor M.C. Lyons – later himself Sir Thomas Adams’s Professor of Arabic – had envisaged him as a lawyer. Being spirited and having single-minded determination, as well as knowing a blind alley on sight, turned him instead promptly into an orientalist, and he sat at the feet of Peter Avery for the next three years. Avery was at the time starting to dip his toes in the 4,500 couplets of the Mantiq al-Tayr of Farid al-Din. In his first two years messing about in boats, both of the sailing and the rowing sort, absorbed some time: Melville pulled his oar at no 2, and the following year at bow, in a strong college (‘May’) eight that successfully fought its way up the bumping ladder. Then in his third year the examiners placed him in the first class in Part II of the Oriental Studies Tripos, ‘acquitting himself with distinction in both classical Arabic and Islamic Persian’ as befits R.A. Nicholson’s prizewinner of 1972. In the same May week, with a civil triumph remarkable in an undergraduate, he put on – in a cavernous lecture room known as the ‘Old Reader’ – a retrospective exhibition of his undergraduate canvasses. This was quite a revelation, for not only were they oils and acrylics rather than sub-lengths of boats, but they were done in greys and mauves of a moody gloom, peopled with wide-eyed weather-beaten beings wrapped into dank draperies. It was altogether the antithesis of the genial and confidently ever-striding undergraduate, well known to all except in this. The plastic arts being commonly alien to English undergraduates, no one else would have exhibited commitment to them.

II

Modern Persian Studies at Pembroke rest on the twin pillars of E.G. Browne (1862–1926) and E.H. Minns (1874–1953), Browne representing the more spiritual and political, and less Parthian, and Minns the more secular, philological, and more Scythian orientation. To the first belongs a flock of political and intelligence officers, administrators, academics and gentlemen-scholars far too numerous to mention at all comprehensively. Like Melville, they typically combine no-nonsense scholarship with a pilgrim soul and sense of adventure, and they stretch from key figures in the engine room of Near and Middle East events since the First World War to such notable modern scholars as Roy Mottahedeh, Soheil Afnan (learned on Ibn Sina), M.B. Loraine (on Muhammad Taqi Bahar) and John R. Perry (on Karim Khan Zand). Among those in the engine room who have put pen to paper are Cecil J. Edmonds (1889–1979), political officer in Mesopotamia and then in Persia on either side of the Great War, a member of the League of Nations’ demarcation commissions for Iraq and Syria who was among Gertrude Bell’s minders and has left, alongside much other scholarship, Kurds, Turks, and Arabs (1957); Laurence Grafftey-Smith (1892–1989), author of Bright Levant, ambassador to Tirana in 1939 and plenipotentiary at Jeddah in 1945; and, perhaps most interesting in a productive set, Laurence Lockhart (1890–1975), who in his professional activity shuttled between the Anglo-Persian (later Anglo-Iranian) Oil Co. and the research department of the Foreign Office. In Isfahan in 1942 this author of Nadir Shah (1938), and author-to-be of The Fall of the Safavi Dynasty (1958), masterminded for Fitzroy Maclean the abduction and transit to Palestine of Gen. Fazlollah Zahedi, whom the Allied powers suspected of Axis sympathies.

Lockhart left striking photographs of the Iran of the late 1920s and early 1950s, which Melville, together with James Bamberg, collated into a beautiful display in the summer of 1999, if memory serves, in the very same Old Reader where over 25 years previously Melville had shown his own canvasses. Lockhart’s photographs of the caravan route from Tehran to Amul and of the Alamut valley, of the Karun river in the high Zagros, of the perfect Khaju bridge across the Zayandeh in Isfahan, and of the almost Venetian waterfront at Bushir are eloquent accounts of the boldness, scale and spaciousness of Iran’s massive and lofty mountain systems, and evocative of its (then) healthy climate, of the clean air of its uplands, and of the abundance of waters that constitute, together with the wonderful hospitality of its people, the ‘common refreshment of humanity’ so attractive to Melville’s mentors, his students and himself.

Du côté de chez Minns this account will not stray far, as that side is too serindian or slavista. There belong Aurel Stein (1862–1943), G.St G.M. Gompertz (1904–92) and various more modern experts, one on Caucasian and Uzbek ikats, in particular. But the two sides did happen to meet in characteristic fashion at Avroman on the Diala river (or Sirwan), west of Senna in Kurdistan. There, in about the year 1909 in a cave a peasant found a hermetically sealed stone jar containing decaying millet seeds and several documents. After these had passed from hand to hand all but three were lost. A local doctor, Mirza Sa‘id Khan, managed to preserve these final three and, on a visit to London, conveyed them to E.G. Browne, who in turn passed the tightly rolled and sealed parchments to Ellis Minns for inspection. One was in Aramaic script, the other two in Greek, and it is these two, exceptional as specimens of non-Ptolemaic Greek script, that attracted Minns’ paleographic interest. Both turned out to be deeds of sale of vineyards, neither conveyances in fee simple, the earlier for a property encumbered at Dadbakanras and sold for 30 or 40 drachmae – the price appeared to have been revised – the later for an unencumbered vineyard nearby at Dadbakabag, sold for 55 drachmae. Ingenious interpretation allowed Minns to date the first quite accurately to November 88bc, that is, in the 225th year of the Seleucid era, and the other to 22/21bc, or A.Sel. 291. This work Minns did in his rooms in the first court at Pembroke, a set he had occupied already as an undergraduate and in whose occupancy Arthur Arberry would succeed him in 1953. It is in those rooms, now on B staircase, that Arberry completed the two volumes (1955) of his respected translation of the Qur’an, as well as his edition and translation of Muhammad Iqbal’s chef-d’oeuvre, the Javid-nama (1932, trans. 1966), so named after the poet’s son. It is curious that of this son, Javid Iqbal, who was subsequently Chief Justice of Pakistan and who happened to be completing his doctoral work at Pembroke in 1954–5, Arberry – ever a withdrawn man – provides not a hint in his introduction to the poem.

III

Melville returned to Cambridge in 1984 to become the moving spirit in Persian Studies, and the next year he was elected to a fellowship at Pembroke. His collegiate curriculum has been quite full: as ‘moral’ tutor for going on three decades (assigned mostly to undergraduates reading Natural Sciences, perhaps because of his knowledge of seismology, or to civilise such pupils); as overseer of the college boat club for half as long, till someone thicker-skinned could be found to replace him in the difficult task of presiding over lively club dinners and commiserating with disappointed crews (if truth be told, Melville’s heart is more a sailor’s than an oarsman’s); and, latterly, as custodian of college pictures and other curiosities. In each of these roles Melville has been a breath of fresh air, best exemplified perhaps in the matter of the curtains of the college hall, or refectory.

Some years ago an eminent mathematician visiting Cambridge was brought into dinner, and in conversation in the combination room afterwards it transpired that he had not appreciated that G.G. Stokes (an occasional seismologist, by the way) had been at Pembroke as man and boy. So to show the visitor the portrait, the door into the hall was straightway unlocked and the lights switched on, only to reveal the world congress of what on the East Coast of the United States are called water bugs. The bursar was roused; a habitat of special scientific interest was found in the pelmets, and the plush red curtains redolent of 50 years of hot meals in common were all promptly eliminated. There followed more than a decade of cacophony, while replacements were inconclusively debated by timorous committees and those dining increasingly raised their voices to hear themselves over their own rising din. At length, however, Melville took an interest, and quite soon finely decorative curtains reminiscent of the greenery in rich oriental tapestry, and not at all of the draperies in his canvasses, appeared. At the same time the college portraits – some more notable for their heavy frames than for the quality of their likenesses – were with pleasant arbitrariness reshuffled by our pinacophylax. It is indeed fitting that a dining room should have provided a stage for some of Melville’s best collegiate activity since, for his bright and engaging manner, his ready hospitality, his désinvolture and sense of fun, his upright outspoken confidence and dismissal of cant, he is quite the most popular dining companion of his generation.

On 15 May 2007, for Peter Avery’s 84th birthday, Melville was the factotum who persuaded the Iranian ambassador (Rasoul Movahedian) to provide the cooks for a memorable Persian dinner at Pembroke, and to honour the much-moved Avery with the Farabi prize on an occasion which coincided with the publication of his masterly translation of the lyrics of Hafiz. An evening marked by toasts, drunk in fruit juice, to President Ahmadinejad and the Queen was rounded off, ahead of further refreshments in camera, by Melville’s characteristically witty and elegantly affectionate, seemingly rambling yet sharply focussed remarks: a speech calling to mind his tall frame like a sail to the wind, breezily rounding the corner of Pembroke Street into college on an ancient bicycle, books in one arm, eccentric handlebar to the other.

Perhaps to this case Sa‘di’s admonition may not apply:

In E.G. Browne’s version of 1924:

Thou who recountest my virtues, thou dost me harm in sooth:

Such is my outward seeming, but thou hast not known the truth.

![]() STUDIES ON HISTORY AND HISTORIOGRAPHY

STUDIES ON HISTORY AND HISTORIOGRAPHY![]() Iran and the Ancient World

Iran and the Ancient World![]()

2

On the epithets of two Sasanian kings in the Mujmal al-tawarikh wa-l-qisas

Touraj Daryaee

The Mujmal al-tawarikh wa-l-qisas is an interesting and, in some ways, a unique text in Persian dated to 520/1126.1 The discussion in relation to the text and its importance has been given masterfully by ‘Allama Qazvini in the preface to the sole typeset edition, published by Malik al-Shu‘ara Bahar in the first half of the twentieth century.2 This version was based on a single manuscript from the Bibliothèque national in Paris, dated to AD 1410. In 2001 an older manuscript, from the fourteenth century, held in the State Library in Berlin, was published in facsimile by M. Omidsalar and I. Afshar.3 This new facsimile, being earlier, helps us to understand better some of the difficulties posed by the text.

The author of the Mujmal al-tawarikh wa-l-qisas is unknown,4 but he seems to have been a historian of good quality, consulting all the previous works available to him and passing judgement on those that seemed fantastic or untrustworthy. In his preface our anonymous author lists all the books that he consulted and there are a few that are lost to us. These texts appear to provide the Mujmal with unique information that cannot be gained from other medieval Arabic and Persian sources.

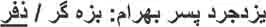

As a small token of appreciation for my colleague Charles Melville, I would like to discuss two of the epithets of the Sasanian kings mentioned in Mujmal al-tawarikh wa-l-qisas, to reconstruct their Pahlavi forms and decipher their meanings. This task has been made possible by the availability of the printed edition of Bahar and the new facsimile edition by Omidsalar and Afshar. The list of Sasanian kings in the Mujmal al-tawarikh wa-l-qisas provides a number of epithets, principal associations and personal names for kings and queens. Some of them include:

| Shapur Hurmuz: Dhū’l-Aktāf |

| Ardashir pisar-i Hurmuz b. Narsi: nikūkār/narm |

| Yazdijird pisar-i Bahra... |