![]()

1

Material culture without objects

Artisan artistic commissions in early Renaissance Italy

Samuel Cohn

Increasingly, scientists employing skills beyond documentary analysis are the ones making fundamental historical breakthroughs. As I write, geneticists, physical anthropologists and evolutionary biologists are rewriting the Columbian exchange between the ‘New’ and ‘Old Worlds’. With DNA analysis and genome sequencing a new landscape of epidemic history in the pre-Columbian New World is being discovered, contesting assumptions about the New World health before Old World diseases invaded. No longer will the pre-Columbian New World be seen in the pristine light as some have previously imagined.1 No documents or even present archaeological findings chart these earlier epidemic contours. Instead, phylogenetic reconstructions pinpointing mutant genes are the keys for mapping this past, and objects – skeletal remains – provide the primary sources.

Art history, of course, has always been object-based. In a reversal of what is now occurring in science-based history, this chapter will contend that the contours of some subjects in art history are, however, imperceptible merely from the study of surviving objects and can be reconstructed only through the analysis of surviving historical documents. Such is the case with much of the art history of those beneath the upper echelons of the elites, at least before the sixteenth century. One such area concerns the art non-elites purchased and displayed in their homes. The mapping of these contours of consumption rests overwhelmingly on documents, principally inventories. As with phylogenetic family trees of pathogens for disease history, research on these documents over the past forty years has transformed our notions of the trends and patterns of consumption among artisans, workers and even peasants. Yet for the ownership and display of paintings, prints and other forms of decorative art in households beneath the horizons of elites, much remains to be done.2

Another world even more dimly lit by surviving objects regards artistic patronage by artisans, labourers and peasants in the late Middle Ages and Renaissance. Evidence of artisans’ commissions comes almost exclusively from one source: last wills and testaments, scattered through notarial books and parchments kept by churches, monasteries, hospitals and occasionally in family archives. Such works of art were commissioned mainly for parish churches and monasteries. A rare exception was a commission by a blacksmith from the Mugello, north of Florence: on his deathbed he bequeathed 14 lire to adorn his bed with an image ‘in the likeness of the majesty of God’ that it be given to the hospital of Borgo San Lorenzo to care for the poor.3 Other commissions for painted or carved figures could cost less, as with a candleholder left by a disenfranchised Florentine woolworker to the hospital of Santa Maria Nuova, which he ordered ‘painted and inscribed’ with his coats of arms, even though this carder possessed no family name.4

The goals of these artisan commissions for embossed candlestick holders, embroidered figures for priestly vestments, panel and wall paintings, and wax figures that could cost less than a florin were not just for salvation. As with pious bequests from elites, those of humble testators expressed desires for remembrance and pr estige in this world as in the next. These patrons demanded to be painted ‘in their very likeness’ (ad similitudinem) and alongside images of deceased family members. Such was a testamentary commission by a blacksmith living in the Aretine hill town, Bibbiena. His modest testament was devoted to one bequest alone: a panel to be painted of the Virgin and Child with St John the Evangelist on one side, and Mary Magdalene and St Anthony, on the other, to be hung close to his grave in the friary of the Blessed Mary. The blacksmith’s instructions went further: on one side, the artist was to paint the blacksmith kneeling at the Virgin’s feet and, on the other, his deceased father. For neighbours and future generations not to miss the point, the blacksmith commanded the artist to label the figures: ‘Here lies Montagne the blacksmith; there, Pasquino, his father.’5

Other artisan commissions could supply more details as with one from an Aretine greengrocer (ortolanus) in his will of 1371. For a mere 4 lire,6 he commissioned narratives (ystorie) of the Holy Ghost to be placed above the altar of his confraternity, probably as the predella of an existing painting.7 At the beginning of the fifteenth century, a man identified only by a single patronymic from the mountain village of Cerreto, northeast of Spoleto, exceeded the simple call for a burial portrait at the feet of the Virgin. He ordered ‘the figure of Saint George with [his name] above his head, the Virgin Mary and child in her arms’, and the testator’s father kneeling at her feet, holding a trumpet in one hand and in the other, flying a flag bearing the arms of the Orlandi family.8 Why the Orlandi’s arms were to be inscribed is not explained. Might the commissioner or his father have been a dependant of this Perugian noble family?9 In the histories of Renaissance portraiture, art historians have yet to evaluate or even recognize this fourteenth-century chapter of donor paintings commissioned in large part, at least in Tuscany and Umbria, by non-elites in their last wills and testaments for spiritual and temporal recognition.

Yet despite their occupations and social status, these testators cannot easily be classified as the poor. Several cases show the economic heights to which artisans could ascend after the Black Death, illustrating shifts in the supply and demand for labour and the new possibilities to purchase landed property.10 In 1361 an Aretine ironmonger left the entirety of his residual estate to build a chapel in that city’s Augustinian church,11 and in 1416 a cobbler from Vinci, who earlier had worked in the poorer parishes sopr’Arno on Florence’s periphery, left 50 florins to construct a chapel to commemorate his remains in his native village. Further, he ordered it to be adorned with a panel painting, depicting the Virgin and ‘the Blessed Saints John the Baptist, the Apostle Paul, Michael the Archangel and Anthony’.12 Even though 50 florins was at the lowest end of amounts to finance the building of a chapel even in village churches as seen in my samples, the cobbler’s expenditure was twenty times larger than the average amount artisans spent on commissioning burial paintings alone. The cobbler, however, had not overreached the possibilities for post–Black Death artisans or their spouses. In 1390, the wife of a belt-maker commissioned a chapel to be constructed in the ancient Aretine abbey of Santa Fiora.13 In 1411, the widow of a tanner ordered the building of a chapel in Perugia’s friary of Monte Morciano.14 And in 1348, the Aretine widow of a weaver (in Tuscany, usually a disenfranchised worker without rights of citizenship) sold all her possessions for one pious bequest, the construction of a chapel in A rezzo’s Santa Maria in Gradibus.15

To explain the rise of the artisan patron, my argument hinges on economics, the shift in wealth spurred by the demographic catastrophe of plagues from 1348 through the Renaissance. As we shall see, the relationship is not what we might have expected. Over sixty years ago, Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie showed that the Black Death reversed a long-term economic pattern of the rich getting richer and the poor poorer in the south of France.16 Since then, historians have shown that Black Death demographics spawned similar economic trajectories for labourers and artisans in other parts of Europe.17 Yet only recently has it emerged just how universal and unusual the post–Black Death century, ca. 1375 to 1475, was in economic history, not only across Europe but into the Near East, and from the thirteenth century to the present.18 No other century has shown such a marked deviation from a generally steady timeline of ever-increasing inequality.19

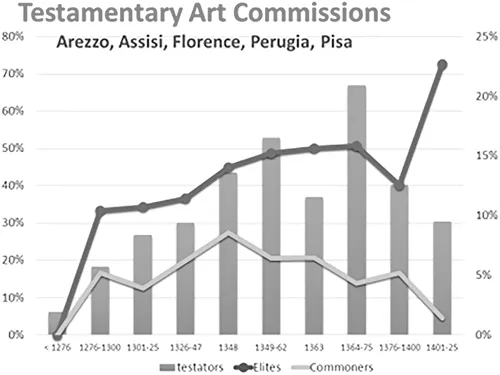

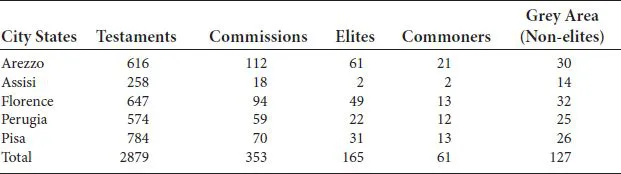

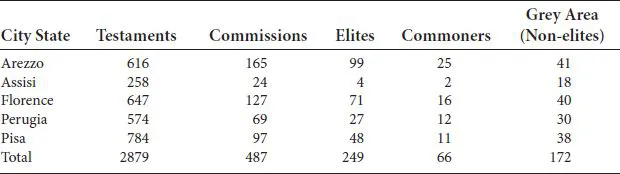

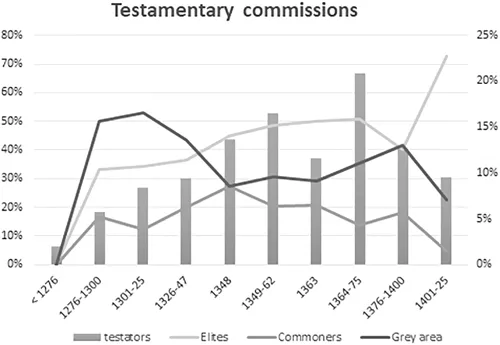

However, artisans’ artistic commissions found in my sample of 2,879 testaments, drawn from archives in five cities and their contadi or regional hinterlands – Arezzo, Assisi, Florence, Perugia and Pisa – do not suddenly increase during the post–Black Death century of increasing prosperity and equality.20 Instead, the relation between artisan commissions and economic well-being was more nearly inversely correlated. Their commissions rose through the first half of the fourteenth century and peaked with the Black Death in 1348. Then, when the economies of Tuscany and Umbria reversed gears around 1375, with textile production rebounding, conditions beginning to improve in the countryside, and the growth of new luxury goods,21 artisan commissions declined sharply and by the opening decades of the Quattrocento had almost disappeared (Figure 1.1 and Tables 1.1 and 1.2).22 Between 1401 and 1425, across all five city states, only two artisan commissioners appear in my samples. When we turn to testamentary commissions of a grey area of non-elites (neither iden tified as peasants, workers or artisans nor by elite occupations, titles or family names), the significance of the changes post-1375 becomes more striking. From the Black Death until 1376, the percentages of artistic commissions to ecclesiastical institutions made by these testators, probably the middling sorts or shopkeepers, continued rising. However, when prosperity and equality began to rise, their commissions dipped as steeply as those ordered by peasants or artisans (Figure 1.2 and Tables 1.1 and 1.2).23

Figure 1.1 Chart: Testamentary Commissions 1276–1425: Elites and Commoners (see also note 22 of Chapter 1). Copyright: author.

Table 1.1 Artistic Commissioners by City State 1276–1425 (see also notes 22 and 23)

Table 1.2 Artistic Commissions by City State 1276–1425 (see also notes 22 and 23)

Figure 1.2 Chart: Testamentary Commissions 1276–1425: Elites, Commoners and an undefined Mixed Group (see also note 22). Copyright: author.

The early Renaissance did not, however, mark a general decline in artistic commissions to churches, hospitals and monasteries. For elites – identified by family names, titles of nobility, and upper-guild professions – the last fifty years of our analysis, 1376 to 1425, registered instead a sharp rise in their commissions, showing a decisive dominance over the ecclesiastic art market . Effectively, their contributions eliminated peasants, artisans and shopkeepers from earlier patronage and their ability to commemorate themselves and their ancestors visually in ecclesiastical spaces.

The price of art was one of the levers that created this scissors-like graphic that opened the gap between elites, on the one hand, and commoners and non-elites more generally. By the beginning of the fifteenth century, the price for ecclesiastical commissions skyrocketed, rising nine times over what it had averaged during the previous generation and a fantastic twenty-six times over what it fetched in the 1360s, despite the period, 1375–1475, being deflationary as far as basic commodities can be measured.24 These prices, however, do not reflect an increase in what individual paintings of comparable materials, dimensions and prestige of the artists might have registered.25 Rather, a complex of items now had become necessary to gain artistic space in ecclesiastical buildings. After 1375, chances of leaving lasting memorials in churches rested on large donations for constructing burial chap...