This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This is a study of the ways various kinds of injury and trauma affected Ernest Hemingway's life and writing, from the First World War through his suicide in 1961. Linda Wagner-Martin has written or edited more than sixty books including Ernest Hemingway, A Literary Life. She is Frank Borden Hanes Professor Emerita at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill and a winner of the Jay B. Hubbell Medal for Lifetime Achievement.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Hemingway's Wars by Linda Wagner-Martin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

The Writer Writes

I ate the end of my piece of cheese and took a swallow of wine. Through the other noise I heard a cough, then came the chuh-chuh-chuh-chuh—then there was a flash, as when a blast-furnace door is swung open, and a roar that started white and went red and on and on in a rushing wind. I tried to breathe but my breath would not come and I felt myself rush bodily out of myself and out and out and out and all the time bodily in the wind. I went out swiftly, all of myself, and I knew I was dead and that it had all been a mistake to think you just died. Then I floated, and instead of going on I felt myself slide back. I breathed and I was back. The ground was torn up and in front of my head there was a splintered beam of wood. In the jolt of my head I heard somebody crying. I thought somebody was screaming. I tried to move but I could not move. (FTA 54–55)1

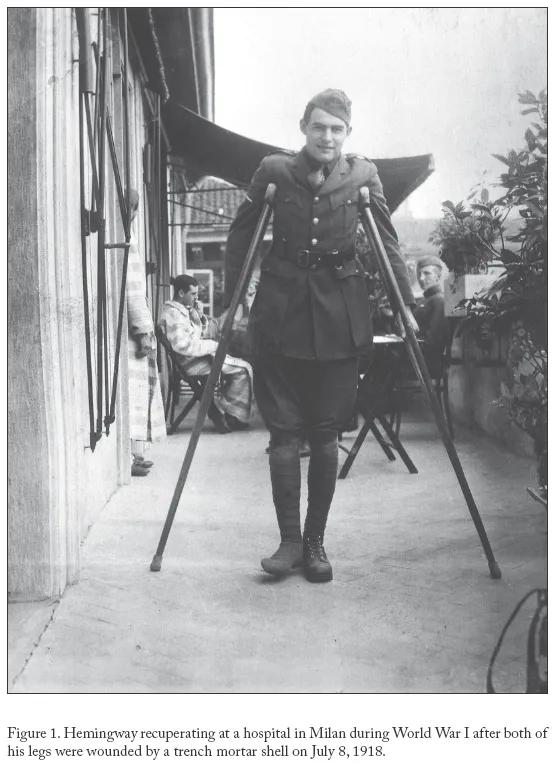

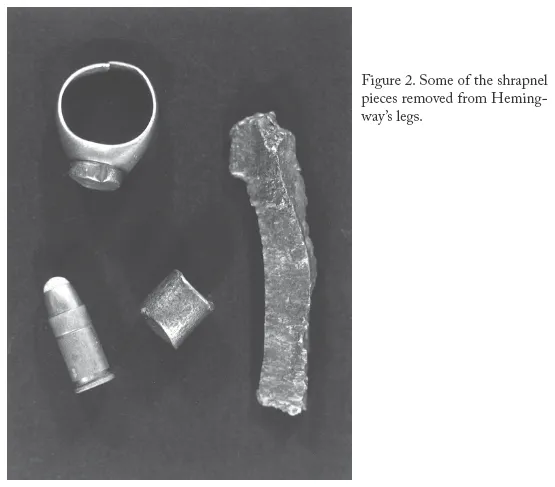

WOUNDED BY A trench mortar shell on July 8, 1918, Hemingway did not write about his out-of-body experience for nearly ten years. Rather than being obsessed with his writerly aim of describing such wounding, he buried the experience in his subconscious and instead practiced, rigorously, the craft of writing.

Hemingway’s physical healing took much of the next two years of his life. Moved from the battlefield site to the newly opened American Red Cross hospital in Milan, Hemingway underwent surgeries (the last on August 10, 1918) as well as extensive physical therapy. He fell in love with the American nurse Agnes von Kurowsky, who was in attendance until she was transferred to Florence. She returned to Milan for several weeks and then was sent to Treviso. After Hemingway visited her there for one day, he considered them engaged. He returned to action but became badly jaundiced and so was hospitalized again. Then the war ended, and he spent the rest of his time in Italy visiting his Red Cross supervisor, James Gamble, in Taormina, Sicily.

Hemingway was discharged from the Red Cross on January 4, 1919, and sailed for New York via Gibraltar, crossing the Atlantic on the Giuseppe Verdi. When he arrived in New York on January 21, he returned home to Oak Park and began convalescing, giving talks, wearing his unofficial “Italian” uniform, hiding alcohol in his bedroom so that he could continue the drinking that had gotten him through his Italian convalescence, writing letters to Agnes, and writing fiction.2

When Agnes sent him a “Dear John” letter in March, explaining that she was too old for him,3 Hemingway became deeply depressed. He went to the Michigan cottage several months before his family came, and he planned to spend the next fall and winter writing there, supported by a small monthly stipend from his Travelers Insurance policy. Part of his anxiety at living at home probably stemmed from his parents’ urging him to go to college. As he wrote in an April 30, 1919, letter, “My family . . . are wolfing at me to go to college. They want me to settle down for a while and the place that they are pulling for very strongly is Wisconsin” (SL 24).

Because most of his writing from these months was never published, exact dates cannot be recovered. But there is enough evidence—given in the biographies about Hemingway’s war and postwar years, particularly those by Peter Griffin, Michael Reynolds, and Charles Fenton—to show that his progress as a competent fiction writer was slow. All three critics excerpt from work that remains in manuscript or was among the writing lost in 1922 when first wife Hadley Hemingway traveled to Schruns with a suitcase filled with Hemingway’s writings—including carbons—and the case was stolen.4 All that remained then of Hemingway’s early writing were several stories already mailed to magazines or carried in his personal luggage to share with other journalists, such as “My Old Man.”

There were stories (and partial stories) about living in Michigan, about the war, and about characters that appear to be drawn from some imaginary small town (perhaps modeled on Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio “grotesques”),5 as well as poems, or perhaps the kind of “poems” he would later collect in both in our time and In Our Time. His word for the brief prose poem he was practicing—and its terse language—was “cablese,” as he told Lincoln Steffens: “Just read the cablese, only the cablese. Isn’t it a great language?”6

Of his early successful short fictions, grouped into a collection Hemingway called Crossroads—An Anthology, among the strongest are those that rely on a concluding irony. “Ed Paige” recounts the townspeople’s disbelief that Paige, a lumber worker, was able to stay in the ring with professional boxer Stanley Ketchel for the allotted time. Paige won the advertised $100 and then (emotionally) retired on his laurels. Later, the townspeople began to question that “wonderful slashing, tearing-in battle.”7

Hemingway used the same kind of scenic structure in “Old Man Hurd—and Mrs. Hurd” as the younger wife laments to the narrator’s mother that she could have married better, “I was a right likely-looking girl then.” But after her father’s death, she could not run the small farm alone. Old Man Hurd would appear every evening and tell her, “Sarah, you’d better marry me.” Like Anderson’s Winesburg characters, Mrs. Hurd had no real choices, so she ended her days married to the man who “has a face that looks indecent. He hasn’t any whiskers, and his chin kind of slinks in and his eyes are red rimmed and watery, and the edges of his nostrils are always red and raw.”8

Sorrow links the vignettes. The often-quoted “Pauline Snow” describes the title character as “the only beautiful girl we ever had out at the Bay . . . like an Easter Lily coming up straight and lithe and beautiful out of a dung heap.” But her friendliness with her only suitor, the rough Art Simons, leads the townspeople to condemn her: “They sent Pauline away to the correction school down at Coldwater. Art was away for awhile, and then came back and married one of the Jenkins girls.”9

If not jarringly dismissive about the collective consciousness of a community, Hemingway’s sketches tried to give insight into men who had served in the military abroad. “Bob White,” which uses another play on significant naming, as in “Snow” and “Hurd,” plays his village for a group of fools, telling them lies about his war (and about French women and their families). His giving listeners “news right direct” is a shameful travesty. Unlike Bob White, “Billy Gilbert,” who joined the Scots Black Watch for a chance to see real action, performed bravely, to the honor of his Ojibway tribe near Susan Lake. But his wearing the required kilt and bonnet makes him the object of his neighbors’ ridicule—his wife has left him, his farm is in disrepair, and “his eyes looked a long way through the dark.”10

Through these stories, Hemingway attempted to write about his war, but his efforts—whether in short pieces or longer—illustrate what critic Jennifer Haytock describes as “problematic.” She notes that the art of writing is, in itself, “a sign of civilization; when a soldier writes about war, he attempts to process a civilization-destroying activity into something that can be understood by civilization.”11

Foreshadowing the kind of results Hemingway would achieve a few years later, as he honed and polished the vignettes that formed the frame of in our time, these early stories caught the essential character not only of the person named in each title but of the culture and of the community, represented collectively.

There are also poems, free-form poems with unrhymed lines that stagger a bit as they try to mimic idiomatic speech, their line divisions creating a semblance of modernist literary finesse. Some of the best are his “Michigan” poems, such as “Along with Youth,” which opens

A porcupine skin

Stiff with bad tanning,

It must have ended somewhere.

Stuffed horned owl

Pompous

Yellow eyed . . . (CP 26)

and some scattered single lines, such as “The grass has gone brown in the summer” (CP 19). These strong lines counteract a sense of quasi-humorous irony that spoils many other of Hemingway’s poems. Among his more accomplished are those about war. Though fewer, they borrow the terse attention to detail so apparent in his journalism. Later published in Poetry, “Riparto d’Assalto” begins with a description of soldiers riding in a cold truck—their physical discomfort and pain, their sexual reveries, and then the ride itself,

Damned cold, bitter, rotten ride,

Winding road up the Grappa side . . .

In keeping with the shock of the war’s deaths for the soldiers, this poem evokes the reader’s parallel shock. Hemingway ends the description of the soldiers’ ride with a single line, naming the place “where the truck-load died” (CP 27). With such other war poems as “Ultimately,” “The Age Demanded,” “Shock Troops,” “Arsiero, Asiago,” “All armies are the same,” “Poem, 1928,” “Captives,” the haunting “Killed, Piave 8th July, 1918,” and “Champs d’Honneur,” the best of Hemingway’s poetry connects “the young Chicago poet,” as the biographical note in Poetry calls him, with war in its various dimensions. In “Champs d’Honneur,” for example, Hemingway’s irony works toward the powerful final couplet, partly because of effective word repetition. The poem opens,

Soldiers never do die well;

Crosses mark the places—

Wooden crosses where they fell . . .

From the pastoral scene of marked graves, the poem takes the reader to the throes of death itself, as “soldiers pitch and cough and twitch.”12 That they have smothered because of an enemy gas attack comes almost as an afterthought at the poem’s end.

In “To Good Guys Dead,” Hemingway warns against the use of abstract words:

Patriotism

Democracy

Honor—

Words and phrases

They either bitched or killed us.13

One of Hemingway’s most poignant war poems signals its autobiographical intent. “Killed, Piave 8th July, 1918” aligns the author’s severe wounding with the mysticism of both pain (“gentle hurtings”) and death, with the threatening presence of the latter described in the poem’s conclusion as

A dull, cold, rigid bayonet

On my hot-swollen, throbbing soul.14

At the heart of Hemingway’s early writing apprenticeship, however, lay the fiction. He saw in the crafting of every phrase, every sentence, the clear difference between the effects he tried for in his journalism and the work that would make his name as writer. In addition to the Crossroads sketches, Hemingway had early written “The Mercenaries,” about the French and American veterans going off to Peru; a now-lost story titled “Wolves and Doughnuts,” rejected by George Horace Lorimer, editor of the Saturday Evening Post; and “Portrait of the Idealist in Love—A Story,” clearly autobiographical and clearly aimed at ladies’ magazines, as was the more complex “The Current—A Story.” There was the more sophisticated “The Ash Heel’s Tendon—A Story,” which brought what Hemingway thought of as his knowledge of boxing and detective work into a plotline, somewhat parallel to that in “The Woppian Way,” a title that biographer Jeffrey Meyers terms a “bad pun on Appian Way. This tale described an Italian boxer, fighting under an Irish name, who gives up a championship fight, joins the Arditi on the Italian front, achieves victory in battle but then cannot return to his tame career in the ring.”15 This last story became a Hemingway staple, titled at times “The Passing of Pickles McCarty.” One might speculate that his long-unpublished story “Up in Michigan,”16 the sexual-predator narrative that used the real names of Jim Dilworth and Liz Coates, drew from both the more realistic early stories such as “The Mercenaries” and the poetic Crossroads sketches. “My Old Man” could be described as realistic as well, with the somewhat cluttered geographic and emotional sections of that story leaving little space for a reader’s intuition.

These fictions also benefited from Hemingway’s becoming a freelancer for the Toronto Star and the Toronto Star Weekly. By a remarkable twist of fate, Ernest Hemingway, the young, wounded ambulance driver, spending the winter of 1920 in his family’s cottage on Walloon Lake near Petoskey, Michigan, while he wrote stories and poems that no literary journal or magazine would buy, was invited to live with Ralph and Harriet Connable’s family in Toronto. Paid to be a mentor and caregiver to the Connables’ teenaged son, he was told he would have ample writing time. True to that promise, Ralph Connable, head of the Canadian F. W. Woolworth chain of stores, gave him the promised free time and paid him a salary of twenty dollars a week.

Ralph Connable was originally from Chicago, where he and Dr. Clarence Hemingway were friends. His summer home on Walloon Lake was near the Hemingways’, and he had known Ernest his entire life. There are alternate stories about this invitation to Toronto: one insists that Harriet Connable was in the audience when Hemingway, wearing his Italian cape and boots, spoke about the war and his wounding. After the talk, she invited him to come live in their guest house, to be a companion to their disabled son. However the invitation came about, it was timely: Hemingway had written a friend that he was down to his last twenty dollars and had been promised a job soon at the local pump factory.17 Another benefit to his going to Canada was the fact that the Connables were friends of both Gregory Clark and J. Herbert Cranston, the features editors of the Toronto Star Weekly.

Hemingway thought of himself as an experienced journalist. Biographer Charles Fenton agreed that he understood a good bit about journalism after his seven diligent months at the Kansas City Star.18 But what the Toronto Star Weekly (the weekend paper) wanted was not reporting: they wanted human interest stories. Hemingway’s first byline for the Star Weekly came as early as February 14, 1920, with a story about local women who paid artists a fee for the use of original paintings for six months. Titled “Circulating Pictures,” the article provided useful information concisely. It was followed March 6 with “A Free Shave,” describing the services of the local barber college, replete with humor and extensive dialogue. The list of Hemingway’s articles is long, averaging one every weekend. Irony, as in “Popular in Peace—Slacker in War” and a tongue-in-cheek “Store Thieves’ Tricks,” was plentiful. Some of the articles were based in nature (several were about trout fishing, others camping). Many were based on local news situations, as in the case of “Fox Farming.” Others stemmed from abuses during, first, the war and, then, Prohibition, and what Hemingway called “Canuck whiskey.”

The Star Weekly provided Hemingway a showcase for his many topics (and their differing treatments). With hardly a break after he left Toronto and returned to Michigan for the summer of 1920, the articles continued, though their topics were less often about Toronto. As Fenton pointed out in his assessment of Hemingway’s skillful adaptation to human interest journalism, “The American and Canadian papers . . . were of such diverse natures that had his relationshi...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- List of Illustrations

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction - Wars and Their Omnipresence

- Chapter One - The Writer Writes

- Chapter Two - in our time, In Our Time and Dimensionality

- Chapter Three - When the Sun Rose

- Chapter Four - To the War

- Chapter Five - Politics and Celebrity

- Chapter Six - Hemingway’s Epics: “The Snows of Kilimanjaro” and For Whom the Bell Tolls

- Chapter Seven - To the War Once Again

- Chapter Eight - After the War: Across the River and into the Trees

- Chapter Nine - The Old Man and the Sea

- Chapter Ten - The Late Years

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index