![]()

1

Almost Christmastime

It was December, 1941, and Christmas was eighteen days off.

—Dorothy Baruch, You, Your Children, and War (1943)

Daddy, is this war?

—Colonel William C. Farnum's seven-year-old son, William Jr. December 7, 1941: The Day the Japanese Attacked Pearl Harbor (1988)

The first Sunday of December 1941 began slowly in Hawaii, a morning of yellow sand, green fields, and blue ocean covered with a bright, peaceful sky and gentle breezes. The hills rolled, the mountains jagged, and the sea shimmered calmly. In military homes, beach shacks, and Sunday schools, little Hawaiian, Portuguese, Filipino, Chinese, Japanese, and kamainas children eased into a warm, lazy Sunday on the island of Oahu. This “Pacific Paradise” seemed remarkably safe and secure despite the world's storming war clouds. As one machinist remembered the quality of that morning, it seemed to have “a dream-inducing quietness.” Another military man from Maine described his newfound paradise as “an island of dreams come true.” But dreams do end, sometimes dramatically. And to Pearl Harbor, especially to the keiki (small children), came auwe: sudden surprise.1

The previous evening Japanese pilots had begun preparing for their own possible deaths during “Operation Hawaii.” Plans had been excruciatingly complex and secret, but now in these hours before dawn, all that remained was contemplation and perhaps a little saki. Some of the pilots wrote farewell letters to their children; one prayed he could watch his baby daughter grow up. Captain Hara reminded the pilots to adhere strictly to the rules of warfare by striking only military objectives. In two waves at 5:30 a.m., 350 Japanese bombers and fighters lifted from their carriers and began flying over 200 miles above a silent ocean for Oahu's Pearl Harbor, homing in on the soft music of Honolulu's radio station KGMB. As Lieutenant Heita Muranaka headed for the island early that morning, he remembered hearing a sweet girl's voice over the radio singing the Japanese children's song, “Menkoi Kouma” (“Come on a Pony”). “Thinking about what would happen to such lovely children and what a change in their lives would occur only an hour and a half later,” Muranaka recalled, “I couldn't listen to it any more and turned off the switch.” As another pilot's plane finally approached the target, Lieutenant Yoshio Shiga distinctly remembered a particular image of Pearl Harbor: “The U.S. Fleet in the harbor looked so beautiful . . . just like toys on a child's floor—something that should not be attacked at all.”2

Unaware of the approaching danger, the children of Hawaii began various early-morning activities that December day. The fifteen-year-old son of a commanding officer started reading his Superman comic book. A little girl, Roberta, watched her brother playing outside with his friend's wooden wagon. The three young children of army officer Harold Kay tried to play quietly in the living room as their parents argued once again about the safety of raising a family in Hawaii. Patricia and Eleanor Bellinger, ages fourteen and eleven, simply slept. Also snoozing sweetly in a bassinet was Staff Sergeant Stephen Koran's week-old baby girl. David Martin, now thirteen, waited while his military father made him a traditional morning cup of cocoa. Ten-year-olds Julia and Frances, twin daughters of General Howard C. Davidson, chased each other around their front lawn. After listening to music on the radio, six-year-old Dorinda Makanaonalani sat down to a family breakfast of Portuguese sausage with rice and eggs. And Charlie Jr., three-year-old son of Captain Charles Kengla, tried to wait patiently for the arrival of his Sunday School bus.3

Jimmy, the twelve-year-old son of Lieutenant Colonel Allen Haynes, stopped to chat with his mother in their kitchen a few minutes before 8 a.m. when terribly loud airplanes suddenly interrupted their conversation. He glanced out the window. “Mother,” Jimmy declared, “those are Japanese planes.” “Nonsense,” she replied, until she too looked out the window to an awful discovery of the first wave of bombers.4

At 7:53, the commander of the naval base muttered when he spotted nine planes making forbidden maneuvers. “Those fools know,” the commander barked, “there is a strict rule against making a right turn!” But his son, suddenly finished with his comic book, stared and pointed: “Look, red circles on the wings!” At that very moment, Japanese commander Mitsuo Fuchida sent the prearranged attack signal: “Tora, tora, tora.”5

When the first plane flew low over their house, little Roberta ran outside to get her brother and his friend out of the front yard. The Japanese plane then “splattered the sidewalk with machine gun bullets. The little wagon flew to pieces on the lawn.”6

Officer Kay wondered why his children were making such a commotion, literally shaking the house right in the middle of this marital argument. When he stopped to quiet them, Kay then spotted the incoming planes. His wife Ann remarked as their debate quickly ended, “Well, it's war all right.”7

After spotting the Japanese planes, Mrs. Bellinger ran to wake her daughters and rush them to the safety of the community shelter. Though still in her pajamas, teenage Patricia did grab her lipstick on the way. The sisters had played hide-and-seek in the shelter years before, but any games became quickly forgotten as other women and children, most of them still in their pajamas as well, began streaming into the Ford Island shelter. “They were white-faced,” Mrs. Bellinger commented. “I kept thinking, what if this caves in and we're covered up. Will I be able to stand it?”8

Lieutenant Coe's three-year-old son did not wish to be cooped up in the Bellingers' shelter, and fearlessly, excitedly, he ran toward the sudden “Fourth of July fireworks.” His desperate father remembered spending “a few breathless moments chasing him down while Japanese planes swooped and circled, machine-gunning the area.” But the oldest citizen on Ford Island displayed little fear either. Eighty-year-old Lucy Mason, whose husband had died at Wounded Knee in 1890, refused “point-blank” to seek shelter. She had twelve canaries at home to worry about, and, Mrs. Mason insisted, those “young Japanese whippersnappers” did not scare her.9

The parents of the week-old baby along with the couple next door at first panicked but then ran to an abandoned concrete cesspool for protection. Recounted Flora Belle Koran, “So we—Marge, the baby and I, and her little Scottie dog—squeezed ourselves into a space about three feet by four feet and about two feet sunken under the ground. It was concrete but open at the top. We were under the banyan tree, and the trucks were parked there because banyan trees are so thick that from the air you cannot spot things underneath them. If one tracer bullet had hit those [trucks' gasoline tanks] . . . I didn't think about it at the time.”10

Still waiting for his cocoa, David Martin pressed his face against the windowpane after hearing the first loud noise, which his father had assumed were planes arriving from California. “Dad,” as David corrected him, “those planes have red circles on them.”11

Julia and Frances, General Davidson's twin daughters, remained unaware of their immediate danger, joyfully picking up shiny pieces of shrapnel in the yard as planes strafed low over their heads. Their mom and dad raced into the yard and pulled the two girls inside to safety.12

When Dorinda Makanaonalani's family breakfast was interrupted by low-flying planes and loud explosions, her father dashed outside to see the source of the commotion, and she darted behind him. “We shielded our eyes from the early morning sun,” Dorinda remembered, “and looked up into the orange-red emblem of the Rising Sun.” Because of the low-flying attack pattern, she remembered seeing the Japanese pilots' goggles and hearing the “rat-tat-tat” of guns as incendiary bullets ripped into their kitchen, setting it ablaze.13

And little Charlie Jr., no longer diligently waiting for his Sunday School bus to arrive, ran impatiently into the house after the first commotion, shouting, “Daddy, there are planes and they go up and come down and they drop round things that go boom!”14

Years later Lieutenant Coe recalled the events during that first wave of Japanese planes from 7:53 to 8:35 a.m. “Officers and enlisted men were making a beeline to their stations,” Coe remembered, “and civilians, women and children, were dashing for the safety of air raid shelters. There was also a hell of a noise overhead and out in the harbor. The sky was thick with planes, and machine guns were chattering madly.” Another military man, Bill Caldwell, recalled fifty years later how the attack assaulted his senses: “the smells of planes and cars and people burning, the smell of gunfire, the sounds of attacking planes diving low, the indelible sound of bombs blowing up the place where you live and work and the air crews you live and work and play with.”15

A local radio station blasted warnings to Hawaiian civilians: “The rising suns have been sighted on the planes' wings! Stay in the house! Get off the streets! Don't look up!” Another Honolulu station announced, “Ladies and gentlemen, this is an air raid. Take cover.” After that brief statement, the station played “The Star Spangled Banner.” Then silence.16

Bombs did not fall only on Pearl Harbor. A Times reporter later noted that “explosions wrenched the guts of Honolulu. All the way from Pacific Heights down to the center of town the planes soared, leaving a wake of destruction.” Japanese pilots also sprayed bullets in the streets of Wahiawa, and planes rolled over Pearl City to drop bombs and torpedoes on “Battleship Row.” After the initial forty minutes, an eerie quiet descended on the island, and everyone living in Hawaii that day would refer to this period between attack waves as “the lull.”17

Navy man Leonard Webb remembered desperately trying to get his wife and baby to safety when the bullets first pummeled their neighborhood. As Webb helped his wife and daughter into their neighbor's car, she yelled to him that the baby girl needed diapers. “Bear in mind that this is Armageddon,” he told his listener, “the end of the world, and my wife has me chasing diapers! And I went back for the diapers!”18

Pedestrians stood watching from Honolulu Hills as the heavy black smoke curled over Pearl Harbor. Soldiers quickly converted the city's largest high school, Farrington High, into a hospital, and medics brought dozens of the wounded men, severely burned from flaming oil and fiery bombs, to the other temporary hospitals at the Marine barracks and mess hall. One officer's sixteen-year-old daughter, though untrained in medicine, recorded names and comforted the dying sailors. “She knelt beside one man after another,” noted the historian Gordon Prange, “cradling him in her arms like a sick child, easing his last moments from the deep well of compassion the Japanese bombs uncapped. As each one died, she gently laid him down, covered him reverently, and moved on to the next shattered patient.”19

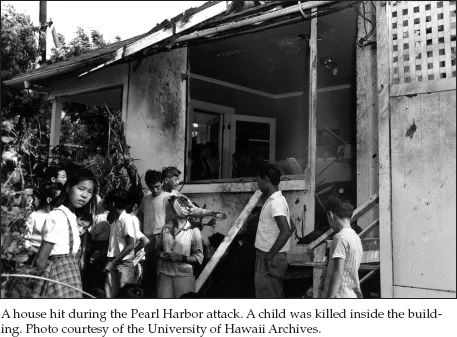

But this had only been the first blast of the Japanese attack. A second wave began hurling bullets, bombs, and torpedoes at the American fleet again at 8:55 until 9:55 a.m., an hour of intense pounding. During this strike, however, more U.S. sailors and soldiers angrily fired back. Civilians, however, possessed few if any defenses. Blake Clark, an English professor at the University of Hawaii, portrayed several scenes during the second wave. “Children were running up the street to where a part-Hawaiian man was holding a limp young girl in his arms,” Clark recalled. “The family of five had been standing on the doorstep when the bomb fell. A piece of shrapnel had flown straight to the girl's heart. The man looked helplessly about him for a moment, then ran up the steps of his home and disappeared into the house with his dead daughter.” Enemy fire killed another girl, a thirteen-year-old watching the attack from her front porch. Clark also remembered all the fleeing women and children in the middle of a close accident: “A plane swooped down, strafing. A machine-gun bullet went through the floor of the truck between Mrs. M and her eight-year-old boy.” A veteran of the attack witnessed “one young mother running while trying to shelter two small heads, one in each arm, crying, ‘My poor babies, my poor babies!'”20

Children lived not only in Hawaiian homes, but some boys had enlisted in the Navy and were stationed right in the midst of the attack. Just before the Arizona blew up, a fifteen-year-old seaman named Martin Matthews (who had managed to sign into the Navy with his father's cooperative deception) would forever remember the chaotic bloodshed of the harbor. “There were steel fragments in the air, fire, oil—God knows what all,” Matthews recalled, “pieces of timber, pieces of the boat deck, canvas, and even pieces of bodies. I remember lots of steel and bodies coming down. I saw a thigh and leg; I saw fingers; I saw hands; I saw elbows and arms. It's far too much for a young boy of fifteen years to have seen . . .”21

Children witnessed other atrocious sights. At first Rose Wong, a teenager at the time, thought it fascinating to watch along with her brothers the Japanese planes flying back and forth over her Honolulu home. “We didn't know that we could've been killed,” Rose explained. Her uncle ordered the children into the house shortly before a nearby bomb struck three teenage boys in a gruesome blast, and Rose remembered burning bits of their flesh and body parts dangling from the neighbors' trees.22

At 11:15 a.m., Hawaii's governor read a proclamation of emergency over the radio and then ordered the local radio stations to shut down, partly because their instructions were frightening rather than calming civilians but also so that radio signals would not act as a homing device for any additional Japanese bombers. Most military men and civilians now firmly believed an invasion was imminent. Martial law with its rules and constraints became effective that afternoon. Fear and panic deepened.23

Later that Sunday afternoon, Janet Yonamine Kishimori, a five-year-old Japanese-Hawaiian child, felt very lucky that she had survived the surprise attack, but she would be haunted by a future she could not have imagined. When the bombing began, her pastor had escorted the Sunday School children to a safer building and then home after the second wave ceased. When she finally reached home, Janet found her mother hiding a picture of Emperor Hirohito so that officials would not consider their family disloyal. For the first time, Janet heard the word “war,” and she remembered her mother's terrified look as if “monsters” had begun attacking the world.24

Some civilians had immediately sought shelter, and others continued to gather together throughout the day. Parents carried dozens of children to Hemingway Hall at the University of Hawaii where those too young to understand played with toys on the floor as dozens of enemy planes roared overhead. One cave offered cover to four hundred women and children; another dugout protected almost three hundred civilians. By midday, some two hundred women and children had crowded the Bellingers' Ford Island shelter. After a number of homes were destroyed, some mothers simply held their children close and dashed to the hills to find hoped-for safety, and dozens of families drove their cars into the sugar cane fields to hide but also to watch the attack above Pearl Harbor.25

The Marines' mess hall and barracks soon fille...