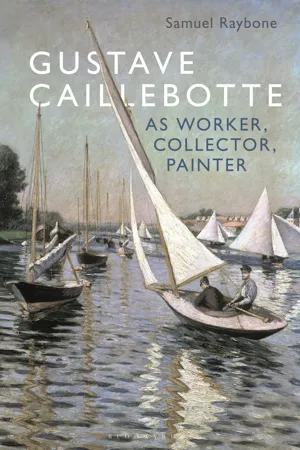

![]() Part 1

Part 1![]()

1

Work

His hat pushed back, hands in pockets, M. Caillebotte came and went giving orders, supervising the hanging of the paintings, and working like a porter, exactly as if he didn’t have an income of one hundred and fifty thousand francs. 1

Gaston Vassy, 1882

It might at first seem strange to begin a book about a man as wealthy as Gustave Caillebotte, ostensibly liberated by his inherited fortune from the necessity to labour, with the problematic of work. Yet, Caillebotte was ill-at-ease with the world of idle leisure and easy privilege into which he had been born and socialized. Caillebotte’s self-portraits, portraits of his fellow bourgeois and scenes of their domestic lives register his ‘ambivalent and conflictive relation to his own class identity’ and his ‘sense of isolation and loneliness’.2 Whether they are gathered round the table for lunch (Figure 2.1) or sat reading alongside one another (Figure 1.4), Caillebotte’s elite milieu interact neither with one another nor with the painter who studies them; likewise, central to the charge of Les raboteurs de parquet (Plate 1) is the hermetic sociability of the labourers and Caillebotte’s inability to imagine his own position as anything but extrinsic. As I will show, Caillebotte came to identify in work the means to reconfigure this liminal and troublesome class identity; he undertook to resolve his alienation through hard work in a manner recognized as such by his contemporaries. Caillebotte returned again and again to ‘the fabrication of his own mirror image’ in terms that emphasized precisely the labour of its fabrication.3

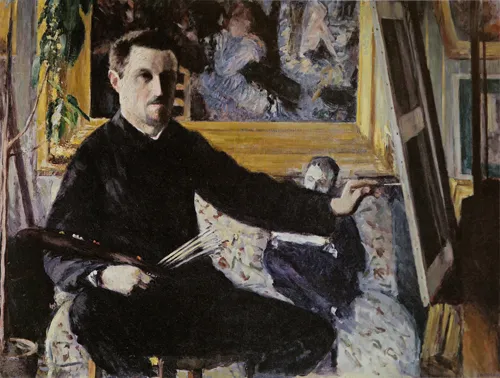

Painted between 1879 and 1880, Autoportrait au chevalet (Figure 1.1) directly thematizes the labour of self-imaging. Keeping his gaze fixed directly out of the frame Caillebotte extends a hand to make contact with the surface of a canvas that is turned and hidden from the viewer. In the background, another figure relaxes on a couch, possibly reading a newspaper. This sofa – which features in other domestic interiors including La Partie de bésigue (Plate 6), Nu au divan (Plate 7) and Intérieur, femme lisant (Figure 1.4) – reveals the location of the scene to be inside Caillebotte’s apartment. Caillebotte sits awkwardly on a stool, half-turned to face the viewer, dressed in a loose, black smock that cuts something of a void in the centre of the canvas.

Figure 1.1 Gustave Caillebotte, Autoportrait au chevalet, 1879–80. 90 × 115 cm, oil on canvas. Private Collection.

Caillebotte has abandoned the precise and polished, quasi-photographic facture that had characterized his most prominent contributions to the 1877 exhibition – Le Pont de l’Europe (Figure 3.1), Rue de Paris; temps de pluie (Plate 2) and Les Peintres en bâtiment (Figure 3.2) – in favour of a looser technique and more textured surface, especially evident in his face. This impastoed thickness impresses upon the viewer the materiality of the painted object (against the voidal black smock, Caillebotte’s colourful palette and bright paintbrushes positively shimmer) and, combined with the obvious iconography of the image, the physical process by which the painting came into being. The awkward pose of the figures, the dearth of social interaction and the inharmonious composition testify to the contrived nature of the scene and genre. The viewer is positioned slightly raised looking down, such that both the top of the room and the bottom of Caillebotte’s legs are cut off. To the left a plant creeps into the frame at a slight diagonal, occupying a nervous liminal existence. To the right of the painting Caillebotte represents in shadow the back of the canvas and the easel that supports it. Although Caillebotte looks out of the canvas to meet the viewer’s gaze, he, like his companion in the background, seems absorbed in a process of visual calculation; we see him, but he d oes not appear to see us.4

This frustrated matrix of gazes, in combination with his ungainly three-quarter pose and the viewer’s centred vantage point, suggests that Caillebotte is here representing himself painting the very self-portrait in which we witness him painting. The viewer occupies the position of the mirror, which Caillebotte studies carefully as he paints his own image, explaining his absorption and inaccessibility to the viewer and fusing the surface of the painting with the surface being worked upon in the painting.5 We will see in other paintings, most notably the Régates à Argenteuil (Plate 3), how Caillebotte became fixated on the hand at work, seen as a conduit between the physical and psychical worlds and as a synecdoche for the entire subjective edifice that that very work constructs and supports. Here, as there, the outstretched hand, in symbolizing the skill and work of the artist, produces this identity by physically connecting Caillebotte with the object of his creation and possession. Composition and motif thus unite in calling the viewer’s attention to the painting’s surface as something worked upon by Caillebotte.

Given the setting of the painting inside Caillebotte’s well-appointed and desirably located apartment on the boulevard Haussmann; the prominence given to Caillebotte’s possessions within the scene; and the heritage of the genre of the artist’s self-portrait as a device for self-promotion, self-imaging and the demonstration of technical mastery, might it be plausible to read this work as an emphatic statement of wealth and possession (as opposed to a somewhat tentative scene of fabrication)? Recent accounts of Caillebotte’s oeuvre have emphasized the prevalence of just such a (classed) desire for possession, a ‘possessive energy’ that caused him to ‘cycle round the theme of his own property’ and to paint Paris as if it was already his.6

Caillebotte was indeed surrounded by and materially dependent upon his property. As critics including Jules Poignard informed their readers, Caillebotte was a ‘rentier’; he lived off income generated by property, government bonds, stocks and capital inherited (in stages and sometimes indirectly, coming via the deaths of René and his mother) from his father.7 As Michael Marrinan notes, Caillebotte had been primed for the life of a héritier and rentier not merely by means of his prestigious education (at the Lycée Louis-le-Grand), but also by having had a childhood thoroughly steeped in his father’s commercial and real estate ventures: ‘the Caillebotte world of business and family’, Marrinan writes, ‘was small and tightly inter-connected’.8 By these two factors Caillebotte was induced into a highly exclusive and privileged world – less than 2 per cent of boys attended a lycée or college – of which being a rentier was increasingly becoming the symbol: in Paris in 1880 one third of lycée students had a rentier for a parent.9

At the turn of 1841–2, Caillebotte’s father, Martial père, spent 45,000 francs buying into a joint venture founded solely to bid for the newly available concession to service the beds of the July Monarchy’s army. Cambry et Cie, as it became known, was very successful, accruing a net worth of over 10 million francs by 1856, and 20 million francs by the time the business was liquidated in 1865. In his role as inspecteur-général-directeur des confections of Cambry et Cie Martial père was responsible for supervising day-to-day operations and was thus required to reside with his family in a house at 160 Faubourg Saint-Denis (later renumbered to 152), owned by the firm and adjacent to its workshops. It was in this company house, next door to the company workshop, that Caillebotte spent the first twenty years of his life.

With the proceeds generated by his participation in Cambry et Cie, in January 1866 Martial père purchased a plot of land on the corners of the rue de Miromesnil, the rue de Lisbonne and the rue de Corvetto, upon which he constructed a luxurious hôtel particulier worth 400,000 francs for the family home, and a four-storey apartment building that generated an income of 20,000 francs annually.10 With the remaining capital, Martial père and three former partners of Cambry et Cie constructed ‘a complex of middle-income housing for artisans, shopkeepers and small-time professionals’ consisting of twenty-two buildings split equally among them.11 It was from Martial père’s share in this enterprise that Caillebotte was to inherit buildings on the rue des Deux-Gares.

Inheriting wealth and deriving sufficient income from that capital not to have to earn income from labour, being a héritier and rentier, were not unusual positions within the class structure of the Third Republic and, indeed, the intergenerational transmission of capital, unhampered by any semblance of progressive taxation and undisturbed by the almost non-existent rate of inflation, was one of the key means by which class-determined inequality was solidified and extended during the Third Republic.12 Caillebotte was among the several hundred thousand who lived off unearned income, and was thus deeply embedded in what Thomas Piketty has characterized as a ‘society of rentiers’, being a direct beneficiary of a highly inegalitarian economy.13 Piketty’s seminal Capital in the Twenty First Century paints a stark picture of precisely how unequal the French (and especially the Parisian) economy was at this moment, data that help us understand the vast chasm of wealth that separated Caillebotte from the working men he painted tending his gardens, planing his floors and manning his yachts. While two thirds of the population died without leaving any wealth at all, the top centile’s share was 60 per cent.14 Wealth was ten times more concentrated than salaries, meaning that an inherited fortune in the top centile enabled a quality of life three times greater than those earning in the top centile of salaries; it paid far more to inherit well than earn well.15 As the rate of return on capital (around 4 to 6 per cent) greatly exceeded growth (which was essentially non-existent), inherited fortunes grew substantially faster than output and income; thus, it was essentially impossible for an individual to reach the top of the wealth pyramid through income derived from their labour alone.16 Moreover, the period of deflation lasting from the 1870s until the 1890s boosted the purchasing power of Caillebotte’s fixed income quite considerably, such that his peers tended to overestimate his income as being between 100,000 and 150,000 francs, around double what it likely was, assuming a 5 per cent return.17

The life of a rentier was defined by the absence of (the need to) work. For Littré he was a ‘bourgeois who lives off his returns, without a trade or industry’; for Larousse, he was ‘the man who lives off his returns[;] one can apply the name [rentier] to whomever possesses capital, property, or currency, which allows him to live without the need to work.’18 As Eugen Weber relates, the rentier, frequently a young man where inheritance was a factor, was understood as one who has ‘retired from business’, who ‘never … faced regular work at all’ and for whom the primary struggle was against ‘boredom’.19 The rentier was moreover understood as offering a conservative bulwark against revolutionary upheaval; as Larousse reports: ‘Governments … realized that the rentier was the complete opposite of a revolutionary; where the latter loves change and upheaval, the former dreads the smallest political variations, to the point of seeing cataclysm in a simple change of cabinet. Thus they [the government] reasoned: create as many rentiers as possible; govern, if you can, a society of rentiers.’20

Marrinan and Marnin Young, who are rare in devoting attention to the specificities of Caillebotte’s rentier status (as opposed to merely highlighting his wealth) assume that as a rentier Caillebotte, of necessity, internalized and identified with the conservative values ascribed that status. For Young, this manifest in Caillebotte imbuing in his pre-1879 paintings ‘the slower, extended time of Realism’ (which he aligns with a conservative mindset favouring stable returns, opposed to the rapid temporality of speculation and finance capitalism he associates with Impressionism proper).21 For Marrinan, it manifest in a wholesale allegiance to the socio-economic basis of the bourgeois Republic, an untempered celebration of the delights of Haussmannization, and the least concern for those actually doing the work from which his comfort and prosperity derived.22 Marrinan identifies in Caillebotte’s painterly vision a powerful possessive dynamic and argues that painting offered Caillebotte a means to take symbolic possession of the objects, spaces, people and commodities to which his economic wealth entitled him.

However, to extrapolate directly from Caillebotte’s class a certain mindset that forms the hermeneutic ground for reading the political economy of his paintings problematically overlooks the possibility for a disparity between Caillebotte’s structural class position and his imaginary relation to that position. Indeed, while they often noted Caillebotte’s wealth, his contemporaries were equally concerned to stress how hard he worked despite it. Eulogizing after Caillebotte’s death in 1894, Gustave Geffroy remembered that

Caillebotte truly had conviction in him, and what he leaves surpasses the occupation of the amateur. He could have taken painting just as an excuse for the interludes of his life, and given himself the easy luxury and uselessness of a superficial painter. He was master of his time, sure of tomorrow, and he had a passion for gardening and boats. All the same he tied himself down [il s’astreignit, implying rigorous discipline] to the labour of painting.23

For Geffroy, it was precisely because Caillebotte subjected himself to the work of painting, because he compelled himself towards useful work and away from useless luxury, that he was spared from being marked ...