![]()

Part I

Life in Strategy

What everybody should know everywhere: That life is fundamentally a merciless game; that man should find his protection in the warp and woof of society; that curbs on man’s instincts constitute the essence of civilized living. Without such protections man is alone in the world, as alone as a beast of prey or as the prey itself, waiting to be devoured.1

—Luigi Barzini

Barzini, an Italian writer and social critic, believes life is a merciless game. Suppose we take that idea seriously. If we do, we are turning our thoughts in a strategic direction. Thinking strategically invokes a unique set of mental moves and concepts, things like reconnaissance (what is the situation), directional heuristics (what should I do), and operational flexibility (how can I prepare for change). Strategic thinking involves objectives, resources, decision points, rules, and constraints. At the abstract level it is all rather dry. Yet those of us who are fascinated by strategy are animated not so much by the concepts as by their implementation in situations fraught with significance. In every life, there are moments of decision that truly matter. Sadly, my wife once found it useful to buy a little children’s book titled What On Earth Do You Do When Someone Dies? 2 That’s a good question. What do you do? What strategies are available, and what are their consequences? Getting moments like this right is the ultimate justification for thinking in airy terms, beforehand, about situations, powers, limits, and goals.

This first part outlines a general strategic approach to the human condition. It introduces the idea of existence as a great game of everything and asks strategic questions about it. What are the playing pieces, the rules, the objectives; who is playing; what does winning look like. The second part looks more closely into specific strategies for playing the game of life. But first we ask: What does it even mean to think of life as a game?

Notes

1 The Italians: A Full-Length Portrait Featuring Their Manners and Morals (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1964), 180.

2 Trevor Romain, What on Earth Do You Do When Someone Dies? (New York: Free Spirit Publishing, 1999).

![]()

1

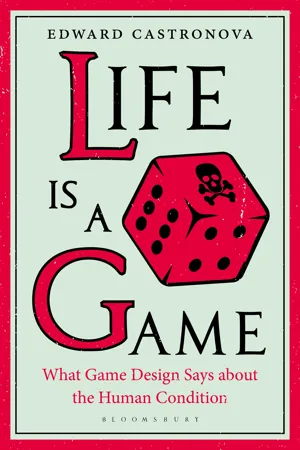

Life Is a Game

Only the man who has grasped this transcendence inscribed in the very essence of participated, created being can truly “play,” for he has laid hold of the mean between gravity and fun, between the tragedy of existence and the light-hearted surrender to the game of life which is mysteriously guided by the goodness of a Wisdom itself, also at play.

—Plato, Laws

The idea that life is a game is old. It is also frequent, going back to the ancient Greek philosopher Plato and beyond. “Life is a game” has been said and written so many times that it would take volumes to list them all. There is nothing new in the idea that we are playing at life. What’s new is how we respond to that idea. We now have a thriving discipline of game analysis, and hundreds of researchers around the globe spend day and night thinking about games, using all the tools in the academic toolbox: data, cultural comparison, social theory, market analysis, and many other things besides. With all this intellectual artillery lying about, we can now take the idea of life as a game seriously. We can analyze life using the same tools that game researchers use to analyze games.

Here is one immediate benefit of doing so. Most people conflate the idea of play and game: we tend to think of them as the same thing, whereas game scholars have determined that they are not. According to game theorists, a game is a set of players, a set of choices, and a system that takes player choices and translates them into player payoffs.1 According to play theorists, play is a structured activity that is not serious.2 The differences are critical to understanding happenings in this area. When two kids pretend to be mommy and daddy, they are playing house. They are not serious (and if they are teenagers, we thank heaven for that). It is not a game, though, because there is no choice architecture, no system that takes what the kids do and translates it into specific rewards. On the other hand, an election is a game but is not play. It has an elaborate choice architecture but is not silly at all.

If we listen to these game scholars, then, we know that the phrase life is a game does not mean that life is silly. It means that life presents all people with choices, and those choices—combined with the inevitable randomness produced by the choices of others as well as Nature herself—come back in terms of gains and losses. This makes sense. The many thinkers who have said that life is a game were not necessarily saying that life is silly, but they certainly were saying that life has good and bad moves.

Take, for example, the quotation that opened the book:

Life is a child, being a child, playing a game.

This 2,500-year-old fragment from the Greek philosopher Heraclitus may be the oldest written reference to life as a game. Heraclitus, like many others, casually uses game and play together. He talks about a child playing a game. Is this a serious situation? Possibly. Children take their play quite seriously, and the subject, which is life itself, is serious. On the other hand, maybe the point is that child’s play doesn’t have major effects outside the world of the child, which make this child’s play unimportant. Whether Heraclitus intends to say that life is silly is not completely clear. However, it is pretty clear that he thinks in terms of choices and outcomes. Playing a game is more than just playing. The philosopher is trying to express how life involves making decisions and watching what happens. “You win some, you lose some” would be an apt response. It would fit. It be an appropriate thing to say, whereas “Nothing really matters” would not. The irony and pathos in the quotation come from the fact that life does matter. Life really does matter, and yet it unfolds as a series of moves and countermoves that give us the feeling that we are tokens on somebody’s game board. We work hard to craft a resume, and we just need things to proceed in a more or less normal way in order to get the job of our dreams; yet when we only need a 2, 3, 4, 5, or 6, we roll a 1 and lose the job anyway. We have all had that feeling, and Heraclitus captures it perfectly: it feels like some kid is playing a game and we happen to be the pawn who goes to the Unemployment Office when the die is rolled. The quotation evokes the feeling that there is a merciless set of rules—designed for somebody else’s entertainment—that will have serious consequences for us.

Some Quotes

To deepen understanding of this idea that life is a game, let’s review some of the ways different authors have expressed it. As we said earlier, there are so many examples that we can only look at a tiny fraction.

Beginning with the ancient Greeks—everything seems to start with them—the sentiment expressed by Heraclitus was part of a general commitment to games in Greek life. The Greeks saw competition as the key to greatness. The philosopher Hesiod proclaimed: “Strife is wholesome for men.”3 Accordingly, games were an important part of Greek culture. Foot races expressed the cultural commitment to getting better by competing with others. The Olympic games occupied the attention of the whole country and, it was said, of the Gods themselves. The games were perhaps intentional models of the way Greeks felt people should live. Intentional or not, the presence of competition in both games and life made a connection apparent. Thus, for Heraclitus, life is like a game.

Moving from Athens to Jerusalem, here is a quote from the Book of Proverbs. The speaker here is Wisdom:

“The Lord begot me, the beginning of his works,

the forerunner of his deeds of long ago;

From of old I was formed,

at the first, before the earth.

When there were no deeps I was brought forth,

when there were no fountains or springs of water;

Before the mountains were settled into place,

before the hills, I was brought forth;

When the earth and the fields were not yet made,

nor the first clods of the world.

When he established the heavens, there was I,

when he marked out the vault over the face of the deep;

When he made firm the skies above,

when he fixed fast the springs of the deep;

When he set for the sea its limit,

so that the waters should not transgress his command;

When he fixed the foundations of earth,

then was I beside him as artisan;

I was his delight day by day,

playing before him all the while,

Playing over the whole of his earth,

having my delight with human beings.”

Prov. 8:22–31

Wisdom describes herself as a worker for God. She takes on the job of building the world, as God’s “artisan” or craftswoman. In doing so, she plays, having delight with us, the people. Fortunately her name is Wisdom, not Anger, Revenge, or Nasty, because in those cases being her pawn would be a bad thing indeed. Being the pawn of Wisdom, however, is a good thing. The delight that Wisdom takes in her people produces a world that is fundamentally good. Wisdom plays, but this is not silliness at all. Instead the lines express the joy that Wisdom experiences in the creation of the game.

Later we have the apostle Paul describing his own life as a game: “I have competed well; I have completed the race” (2 Tim. 4:7). The word competed stands out here; Paul is satisfied that he played the game well and made good moves.

Maximus the Confessor (AD 580–662) expresses it like this:

We speak of the playing of God, who through this creative pouring out of himself makes it possible for this creature to understand him in the wonderful play of his works; who has made for us children’s toys out of the bright and variegated forms of his world.4

This quote is from a remarkable book called Man at Play, by Jesuit father Karl Rahner, that, to my knowledge, has not been cited in the literature on play. Rahner’s work uncovers the idea of play throughout the vast tradition of Western theology and philosophy. The book’s preface, by Jesuit priest Walter Ong, remarks that we have always known that life is a game:

“When we turn to work activities to see which of them are mixed with play, we find they all are. We have always known this, in fact: Life, we say, is a game.”5

Rahner’s goal is to support this assertion by citing writers from century upon century. As a priest and theologian, he naturally focuses on the Christian philosophical tradition. It may be surprising to some that the medieval church was a hotbed of game thinkers, but Rahner makes the case persuasively. Ong points out that the Latin ludus, used by many game scholars to ennoble our field (“ludology”), means both play and school. Rahner repeatedly uses the term ludimagistri in the sense of “masters of play.” Who knew there was a Latin phrase for DM.6

Rahner, as a theologian, believes that the point of this game of life is virtue, more specifically, getting into Heaven. We will return to this idea in a later chapter devoted to the religiously orthodox approach to the game of life.

Medieval thinkers were comfortable with the idea of we are part of a vast game, and naturally it is implicit in the work of later philosophers. Seventeenth-century mathematician Blaise Pascal took a game-like view when proposing his famous wager.7 The wager can be briefly described as follows. What if the existence of God was itself the outcome of a roll of the die? If you roll a 1, God exists; otherwise he does not. If you were in that game, argues Pascal, you would be stupid to deny the existence of God. Why? Because of the way the consequences play out. If you choose to be a believer, a 1 sends you to Heaven and eternal bliss. A 2–5 only means that you have wasted some time sitting in church, worshiping a God who is not there. But if you decide to be an atheist, a 1 condemns you to eternal Hell and a 2–5 gets you nothing. According to Pascal, eternal Hell is so bad and eternal Heaven so good that a rational person should choose to be a believer. It’s better to face a 5/6 chance of wasting time in church than a 1/6 chance of burning forever.

In the twentieth century, writer Stefan Zweig similarly saw humankind as players of a difficult but important game:

Some strange deity has set us down in our seat at this gaming table of a world. If we wish to amuse ourselves there, we must accept the rules of the game, taking them as they are, without troubling to inquire whether they are good rules or bad.8

Zweig’s attitude seems close to Heraclitus: there is an irony we cannot avoid, because we have been placed without our permission into a game whose rules we did not design. We have to take the game as it is, even if it seems unfair.

According to moral philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre, the game is important and extremely beneficial because it gives us meaning.9 In the later parts of After Virtue (1981), MacIntyre invokes the notion of quest to identify the practices that give meaning to life. Quests are essential to a life well-lived: they solidify our sense that we have something to do, our sense of purpose. Without quests, life would be terribly boring, and this is MacIntyre’s diagnosis for the ills of the world today. The modern world, he says, has lost its quests.

More recently, there have been interesting and quite direct analyses of life as a game. In The Grasshopper, Bernard Suits describes a dream world in which

“everyone alive is in fact engaged in playing elaborate games, while at the same time believing themselves to be going about their ordinary affairs . . . . Whatever occupation or activity you can think of, it is in reality a game.”10

The same point is made in Borges’s “The Lottery in Babylon,” which describes a lottery which becomes so big and all-encompassing that it controls everything in life.11 Playing games is not an idle pastime but the most important activity imaginable. In this, he echoes game designer and educator Bernard de Koven, who also argues that if we had nothing functional to do, we would do nothing but seek well-played games, and be all the better for it.12 Similarly, James Carse in Finite and Infinite Games comes to the conclusion that “there is but one infinite game” within which all othe...