This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

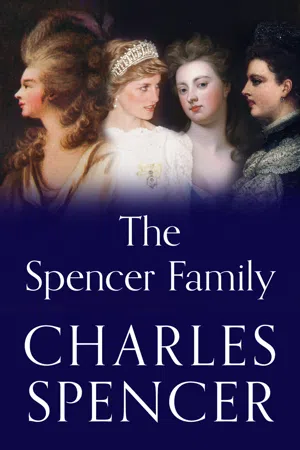

The Spencer Family

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

From the bestselling author Charles Spencer, a brilliant insider’s history of the Spencer family.

Travelling centuries through the Spencers’ family and their wide-ranging roles in Britain’s history, Charles moves from the sheep-farmers of the sixteenth century through the Civil War to the 19th century when the third Earl was one of the architects of the 1832 Reform Bill, and up to recent years and the death of Princess Diana.

Filled with new visions of great historic events, odd characters and intimate personal matters, this is a hugely satisfying history of one of England's great families.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Spencer Family by Charles Spencer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1. The Despenser Debate

Though this is a book that purports to deal in definites, it needs to begin with a ‘maybe’.

There has been much debate about where the history of my family can be seen to have begun. The version I was told, by Grandfather, was categorical: ‘The word “Spencer”,’ he told me when I was a boy, ‘derives from the Norman word for Steward, or Head of Household: “Despenser”. Our common ancestor was Steward to the household of William, Duke of Normandy, joining his master at the Battle of Hastings, in 1066, and subsequently settling in England, when the Duke became King of England.’

Grandfather’s forte was the Spencer family’s history, and it was unwise for anybody to challenge him when he expounded on his specialist subject with confidence. The result was ill-disguised contempt and the risk of permanent banishment from Althorp. The fact is, he was nearly always right; and, in the rare instances when his interpretation of events was open to question, it was best not to pursue the matter too closely.

If we look at supporting evidence for Grandfather’s Despenser claim, it is beyond doubt that one Robert Despenser was William’s steward, and that he did accompany his master on his successful invasion of England. We also know that Robert, although head of William’s household, was not a mere member of the domestic staff, but a powerful lord in his own right, holding his court position to augment his influence with his master. In England he was one of the most significant of the new class of magnate that the Crown was forced to rely on, in the late eleventh century, to ensure the ultimate success of the Norman conquest.

Thus we see Robert’s name alongside those of other barons who assembled in Council with William I, in London, in 1082. The following year, when the same members of the Council ‘set their Hands and Seals to the Charter of the King, for removing the secular Canons out of the Church of Durham, and placing Monks in their Stead’, Robert’s signature was on the document. The first recorded Despenser was also viewed as a powerful enough figure to act as witness to the King’s Act, which granted the city of Bath, with its coinage and toll, to John, Bishop of Bath, for the better support of his see. As for the monks of Worcester, they termed Robert Despenser ‘a very powerful man’. They should have known, since it was Robert who had seized the Lordship of Elmleigh from them, which they never regained.

Understandably, the Despensers jealously kept their senior court position in the family. Robert’s son, William Despenser, became steward to Henry I; as did William’s own son, Thurston, after him. On Thurston’s death, his son Walter, Lord of Stanley and Usher of the Chamber of Henry II, maintained the Despenser tradition of being mighty courtiers. Walter’s younger brother, Americus, settled in the tiny Midland county of Rutland, where he was sheriff in the 1180s, before following the family practice by becoming steward to Richard the Lionheart.

The close association between the Despensers and the monarchs of medieval England continued into the next generation, with Americus’s son, another Thurston, a baron in King John’s time, extending his influence into the reign of Henry III, when he was Sheriff of Gloucester, until his death in 1229.

It was at this stage, during Henry III’s fifty-six-year reign, that the Despensers were transformed from being important figures in the royal court, to numbering themselves among the most powerful handful of men in the land. Hugh Despenser, Thurston’s heir, was one of the twelve barons nominated by Henry III to amend and reform the laws of England. However, there were growing tensions between Henry and his barons, which were brought to a head when the monarch attempted to buy the kingdom of Sicily for his son, for a sum that the barons thought grossly inflated, and therefore contrary to the nation’s — and their — interests. In the ensuing civil war, Hugh Despenser was chosen by his peers to be Justiciar of England. This meant that he was entrusted with supreme control of the jurisdiction of the Law Courts of England.

Hugh fought against Henry III at the battles of Northampton and Lewes, at both of which he was noted for outstanding personal bravery. The military strength of the barons, under Simon de Montfort, resulted in Henry being taken prisoner at Lewes, giving the barons their greatest hold on power to date. To underline his humiliating loss of control, in 1265 King Henry was forced to send writs to all the cities, burghs and towns on the coasts of Norfolk and Suffolk, stipulating that he was no longer their effective master; instead, Hugh Despenser was to be obeyed in everything he instructed them to do.

Hugh and his allies had little time to enjoy their new-found power for, in that same year, 1265, they were vanquished at the battle of Evesham in the most crushing defeat on English soil since Hastings two centuries earlier. Despenser met his death on the battlefield, after again fighting valiantly.

The Despenser mantle was next taken up by Hugh’s son and grandson, who shared the dead man’s lust for power, as well as his first name. Given the plethora of Hugh Despensers at this stage, these two Hughs are often referred to as Hugh Despenser Senior, and Junior. They were two of the most able and ambitious men of their age. As their destinies would show, however, this was not an age noted for its compassion.

Hugh Despenser Senior was a successful soldier and diplomat under Edward I, serving him militarily in the four spheres of operations that dominated English foreign policy at the time: France, Flanders, Wales and Scotland. While Hugh Senior was summoned to Parliament as a baron, his son, also noted as a loyal servant to the Crown, received a knighthood. It was under Edward II, however, that both Despensers were to reach the peak of their power and influence.

I have always felt sorry for Edward II: his record as king is one of the more pitiful in British history. Sandwiched between the military triumphs of his father, Edward I, known to posterity as ‘the Hammer of the Scots’, and the equally rugged and successful Edward III, the effete Edward II is only really remembered for two things: having his army trounced by Robert the Bruce at Bannockburn in 1314, and being put to death by his homophobic enemies through the insertion of a red-hot poker into his rectum. From such mishaps it is hard to salvage a dignified reputation for posterity.

It was Edward’s close attachment to his royal favourites that was to be the chief focus of aggravation and destabilization throughout his adult life. Although those who would openly oppose Edward were to justify their rebellion as a just attack on ‘the evil counsellors’ who were perverting the King’s mind, to the detriment of his subjects, the real issue was one of power, and who should exercise it.

By the time that Edward II came to the throne in 1307, the barons of England were once again attempting to chip away at the might of the monarchy. They resented the power that still lay with members of the royal household, and the King’s prerogative that such a system of patronage reinforced. The barons believed that their might in the provinces should be recognized by the transfer of more executive authority into their hands. The result was friction, and revolt.

Edward II’s blatant reliance on his deeply unpopular Gascon lover, Piers Gaveston, gave the opposition barons a focus for their self-serving discontent. However, it was the Despensers who, for the latter years of the reign, were to galvanize the King’s enemies into open conflict with the Crown.

It has to be admitted that both Despensers were appallingly ill-advised choices as royal favourites. Early fourteenth-century Britain was not short of controversial figures, but they all had their apologists, who would write justifying the actions of the key personalities of the time. All, that is, except my supposed ancestors, the Despensers, who attracted not one page of defence from their contemporary chroniclers.

The universal contempt for the Despensers stemmed from their transparently rampant personal ambition, particularly after 1322, when they amassed an unseemly quantity of possessions and privileges for themselves, weakly handed to them by an increasingly dependent Edward. The two Hughs became, respectively, Earls of Winchester and of Gloucester, as well as owners of huge landed estates: at one stage, the Earl of Gloucester was calculated to own fifty-nine lordships in various English counties. There he kept his massive number of livestock, which amounted to 28,000 sheep, 1,000 oxen, 1,200 calving cattle, 40 mares with colts, 160 drawing horses, 2,000 hogs and 3,000 bullocks. In his various homes, there was estimated to be 40 tons of wine, 600 bacons, 80 carcasses of Martinmass beef, 600 muttons, 10 tons of cider; armour, plate, jewels and ready money, worth more than £10,000, as well as 36 sacks of wool and a great library of books.

This bountiful abuse of an ineffectual monarch was to spell the Despensers’ doom: breaking point came when the younger Hugh prevailed on Edward to give him a barony, which it was contentiously claimed had reverted to the Crown. There followed an insurrection in the kingdom, in 1326, whipped up by the discontented lords, but soon spreading throughout the land. As the Abbé Millot recorded in his History of England: ‘London revolted from Edward; the provinces followed the example of the capital; and the king, disappointed with regard to the loyalty of his subjects, took to flight.’

The beleaguered Edward II and the Despensers refused to break ranks with one another. Hugh Senior was cornered in Bristol, where he was handed over to the barons by his own men. The old man, being in his ninetieth year, might have expected a modicum of mercy; but it was not to be. Indeed, he failed even to be granted a trial, and was condemned to death, unheard. It was ordered that his execution should be that of a common criminal, and so he was hanged. The King and the younger Hugh were forced to watch his grisly end on the scaffold before them.

Despenser Junior had avoided the same fate by agreeing to surrender voluntarily, while holed up in the castle of Caerphilly. In return, his captors had solemnly guaranteed the safety of his life and limbs, hopeful that, after witnessing the demise of his father, Hugh would finally desert his king. However, this he would not do; so he was turned loose. He had overlooked the need, in such ruthless times, of extending his period of invulnerability, though, and he was almost immediately recaptured. This time the only guarantee he had was that he would be treated without mercy, and in that he was not to be disappointed: on 28 November 1326, he shared his father’s fate; the only consolation, for a descendant, lies in the fact that it was very much preferable to sharing that of his monarch.

Unsurprisingly, given the brutal deaths of the three preceding heads of the family, the Despensers chose to adopt a lower profile over the following generations. There was a royal marriage of sorts, when Hugh Junior’s grandson Thomas, Earl of Gloucester, wed Edward III ‘s granddaughter, Constance. The only son, Richard, died when just fourteen, and with him was extinguished the senior line of the Despenser family.

*

Grandfather’s contention was that our family sprang from a junior branch of the same family: from Geoffrey Despenser, in fact, the brother of the first of the three Hughs, the courageous figure slain at the battle of Evesham. We know little about Geoffrey, except that he was the first founder of Marlow Abbey in Buckinghamshire, and was a witness to Henry II’s Confirmation of Lands to Bungey Abbey in Suffolk. Later in Henry II’s reign, there is record of the donation by Geoffrey Despenser of the Church of Boynton to Bridlington Priory.

When he died, in 1251, Geoffrey left a son and heir, John, who was a minor. When he came of age, four years later, he was knighted by Henry III. This John was influential enough to obtain, in 1256, the Bull from Pope Alexander, which directed the Bishop of Salisbury to agree that ‘John Despenser be allowed to build a chapel, and have a chaplain in his manor of Swalefield, which John is prepared to endow, since the manor lies in a forest, making it unsafe for him and his family to go to the main church near-by, because of the amount of criminals lurking in the said forest.’

John was a man of war rather than a man of God. He joined the barons against Henry III, and was taken prisoner at the Battle of Northampton. His manors of Castle Carton and Cavenby, in Lincolnshire, were confiscated. But the barons prevailed and Sir John was released in 1264.

His son and heir, William, has left behind almost no trace of his existence. All we know about him is that he styled himself ‘William le Despencer of Belton’; and he lived at Defford, where he died during the reign of Edward III. His son, John, was a more remarkable figure, serving in the retinue of John, King of Castile, in his voyage to Spain, as a result of which he received the King’s Letters of Protection for one year, dated 6 March 1386. On his return to England, he became a Squire of the Body to King Henry V, as well as Keeper of his Great Wardrobe. John accompanied his monarch, one of the most heroic English personalities of the Middle Ages, on his expeditions to fight in France.

John and his wife Alice had a son, Nicholas, who was the father of Thomas and William Despencer. The elder of the two, Thomas, produced Henry Spencer (the first time the name was used in the family without its Norman prefix of ‘De-’), of Badby, Northamptonshire, the county which, beyond all others, has been associated ever since with the Spencer name.

Henry married Isabel, with whom he had four boys. When he died, in 1476, Henry’s last will was sealed with the coat of arms that the family still bears today.

There have been those who have disputed Spencer claims to spring from the same blood as the mighty Despensers. Certainly, on the page, the case appears proven. I hope I can be forgiven for going through the family tree in such detail, but I feel it is a helpful exercise in order to explain Grandfather’s thesis, while being aware that, at times, the preceding paragraphs must have all the appeal of one of those interminable chapters in Genesis, where so and so begets someone or other, seemingly ad infinitum.

It would not have been necessary to write down all the various links if the Despenser claim were undisputed; but that is not the case. At the time that the Tudor Spencers claimed such links with their presumed forefathers, they were accepted without question; indeed, as late as 1724, a contemporary chronicler was able to confirm that Althorp was ‘the manor and seat of the noted Family of the Spencers descended from the ancient Barons Spencer of whom Hugh Spencer the Father and Son, favourites of King Edward II were’.

But in 1859, Evelyn Philip Shirley, in The Noble and Gentle Men of England, was a little more sniffy about the Despenser connection, although he failed to specify where the problem lay: ‘The Spencers claim a collateral descent from the ancient baronial house of Le Despencer,’ he wrote, ‘a claim which, without being irreconcilable perhaps with the early pedigrees of that family, admits of very grave doubts and considerable difficulties.’ Shirley concluded his judgement with a concession, though: ‘It seems to be admitted that they descend from Henry Spencer [of Badby].’

The highly knowledgeable historian William Camden was convinced by the Despenser link, accepting the above family tree in full, and yet contemporary commentators still hold the claim as being open to question. In the course of compiling this book, I have studied the family papers in some depth, and fail to see where the problem lies. Perhaps, by the end of the eighteenth century, it just looked unnecessarily greedy and self-serving for the Spencers to claim prominence and position so very far back in the annals of the history of England?

Writing 200 years ago, Sir Egerton Brydges, the editor of Collins’s Peerage, struck on a compromise position over this matter, which hints that my theory may hold some water: ‘The present family of Spencer are sufficiently great,’ wrote Brydges, ‘and have too long enjoyed vast wealth and high honours, to require the decoration of feathers in their caps which are not their own. Sir John Spencer, their undisputed ancestor, and the immediate founder of their fortune, lived in the reigns of Henry VII and Henry VIII; and three hundred years of riches and rank may surely satisfy a regulated pride.’

I am happy to settle for that. I doubt whether Grandfather would be too pleased about it, though.

2. The Early Spencers

My family was never very imaginative with Christian names. Perhaps having a surname as solid as ‘Spencer’ led them to think that it had to be counterbalanced by something similarly uncompromising in its simplicity? At least this would explain the vast preponderance of ‘Johns’ in the family tree: my brother, who died soon after birth in 1960, was the thirteenth eldest son to be given the name in a little over 500 years.

As a result, prior to my family being created peers, and after they were established as rich landowners in the Midlands, we encounter a succession of Sir John Spencers. The first of these was the eldest great-grandson of Henry Spencer of Badby, who had first borne the modern Spencer name and coat of arms. By the time this Spencer — let us call him ‘Sir John’ — was a man, his branch of the Spencer family had begun to concentrate its land and talents in the heart of the English Midlands — specifically in Warwickshire, which was the centre of the burgeoning English wool trade.

By early Tudor times, at the end of the fifteenth century, sheep farming had become a significant industry. The weaving of wool, together with the manufacture of flax and hemp, was greatly improved by the arrival of cloth-dressers who had fled to England after persecution on mainland Europe.

To some, the trend of turning ploughed land over to grazing was deeply unsettling. Sir Thomas More, in his Utopia, written at the start of the sixteenth century, decried ‘the increase of pasture, by which sheep may be now said to devour men and unpeople not only villages but towns’. Apart from the social upheaval implicit in this change of land usage, there was also resentment, again vocalized by More, that the sheep ‘are in so few hands, and these are so rich …’, allowing unscrupulous and greedy men to raise ‘the price as high as possible’.

Sir Thomas may well have had John Spencer in mind when launching this attack, as his herds were famous throughout England for their size and strength. However, there is no record of Sir John I having been either unscrupulous or heartless. A shrewd marriage to Isabell Graunt had secured for the Spencers the addition of an excellent inheritance at Snitterfield, also in Warwickshire; but, otherwise, it was through skilful husbandry that he managed to build up his landholdings so consistently. Five centuries on, the two key estates — Wormleighton and Althorp — remain in my family’s hands, both still demonstrating the fertility and quality that attracted Sir John’s interest all those generations ago.

The family’s association with Wormleighton dates back 530 years. It is a village close to the Three-Shire Stone which marks the junction of Warwickshire with Northamptonshire and Oxfordshire. On a clear day the Malvern Hills can be seen to the west, while from the roof of the tower in the village, Coplow in Leicestershire and the city of Coventry are both visible in the distance. My father told me that this beautiful hamlet marks the furthest point from the sea in all of England.

The earliest deed relating to Wormleighton in my family documents dates from the reign of King John, at the beginning of the thirteenth century, and is a record of a grant of services from seven acres of land by Cecilia, widow of Simon Dispensator. By coincidence, ‘Dispensator’ is the Latin word for ‘Despenser’, or steward.

It was not until John Spencer, father of Sir John I, that my family had direct dealings w...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1. The Despenser Debate

- Chapter 2. The Early Spencers

- Chapter 3. A Poet in the Family

- Chapter 4. A Worthy Founder

- Chapter 5. The Washington Connection

- Chapter 6. Death for the King

- Chapter 7. Products of their Age

- Chapter 8. The Spencer-Churchill Match

- Chapter 9. The Manipulative Matriarch

- Chapter 10. A Secret Marriage, a Public Love Affair

- Chapter 11. Duchess of Devonshire, Empress of Style

- Chapter 12. From Nelson to Caxton

- Chapter 13. Honest Jack Althorp

- Chapter 14. Fourth Son, Fourth Earl

- Chapter 15. Father Ignatius

- Chapter 16. The Red Earl and the Fairy Queen

- Chapter 17. More than a Mere Dandy

- Chapter 18. The Curator Earl

- Chapter 19. From My Father to My Children

- Selected Bibliography

- About the Author

- About the Publisher