eBook - ePub

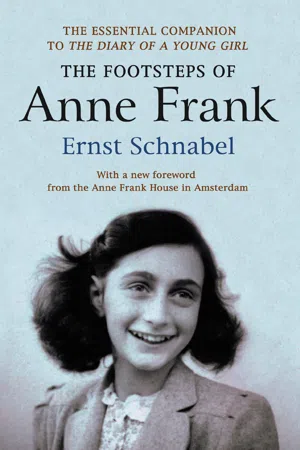

The Footsteps of Anne Frank

Essential companion to The Diary of a Young Girl

This is a test

- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Footsteps of Anne Frank

Essential companion to The Diary of a Young Girl

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The only book that gets close to defining who Anne Frank was. Her father Otto Frank initiated this project and the author interviewed 42 people mentioned in her diary. Here too is the story of the betrayal and its disastrous aftermath.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Footsteps of Anne Frank by Ernst Schnabel, Erika Prins, Gillian Walnes MBE in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Biografías históricas. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

HistoriaSubtopic

Biografías históricasCHAPTER 1

The Focus and the Paths

I have followed the trail of Anne Frank. It leads out of Germany and back into Germany, for there was no escape.

It is a delicate trail, winding to schools and through dreams, across the borders of exile to the threshold of her hiding place – and at the end becoming the pathway to death. It has been smudged by time and forgetfulness. In my search I followed up seventy-six persons who had known Anne and accompanied her some little distance, or had themselves gone similar ways, or who had knowingly or unknowingly crossed her path. Fifty of them were persons I found named or mentioned in Anne’s diary. The names of others were given me in the course of my search or I ran across them by chance. Of these seventy-six persons, I found only forty-two. Eighteen were dead; only seven had died natural deaths. Ten others were either missing or, I was told, had left Europe. Six, I was unable to find at home. But forty-two persons have told me or written down for me what they remember of Anne. Some of them possess little mementos of her. There are photographs, brief pencilled greetings in the margins of letters from her parents, two swimming medals she won, a child’s crib, a strip of film, an entry in a register of births and in a class roll, an outgrown wrap. There are, in short, small relics, little stories, and memories like wounds.

This book contains the testimony of my forty-two witnesses, as well as documents relating to the German occupation of the Netherlands and some hitherto unpublished jottings and stories by Anne Frank. Taken together, they do not make a biography, for, as I have said, the child has left only a faint trail behind her. She was gracious, capricious at times, and full of ideas. She had a tender, but also a critical spirit; a special gift for feeling deeply and for fear, but also her own special kind of courage. She had intelligence, but also many blind spots; a great deal of precocity alongside extraordinary childishness; and a sound and infrangible moral sense even in the most hopeless misery. All in all, she seems to have been what the Greeks would have called a good and beautiful person. The trail we follow here tells us a great deal, but it fails to tell us one thing: what was the source in this child of the power her name exerts throughout the world? Was this power, perhaps, not something within her, but something outside of and above her? It would be the task of a biography to explain both the person and this mystery.

We who today feel this power invoke more than the shadow of her personality when we pronounce the name of Anne Frank. We also conjure up the legend. My witnesses had a good deal to say about Anne as a person; they took account of the legend only with great reticence, or by tacitly ignoring it. Although they did not take issue with it by so much as a word, I had the impression that they were checking themselves. All of them had read Anne’s diary; they did not mention it. Some had also had the courage to see the play based on the diary, but they remained taciturn whenever it was referred to. It was as though they were alienated, not by the play itself, but by the strange unsettled quality of a story that belonged to their own story. They had not entirely deciphered it yet in themselves, so that in these conversations I sometimes felt as if I were interrogating the birds to whom Francis of Assisi spoke, and they answered me: He spoke to us. What more is there to say?

For that reason Anne Frank appears here as a frailer and less dominant figure than the Anne Frank of the diary, or the Anne Frank who crosses the stage night after night somewhere in the world, entangled in life, inhabiting the ramshackle sets which represent her hiding-place, wearing a different face in every theatre, but everywhere having the same irresistible power to move us. Here I must speak of a child who was like countless other children. That must be so, for in truth she was so. Anne was a child, and not one of the witnesses claimed that she had been a prodigy, in any way out of the ordinary, moderate course of nature. She kept a diary. And she wished to live after her death.

In her diary Anne reported on approximately one-seventh of her span of life. She addressed her imaginary ‘Kitty’. The seven persons who were hidden with her in the ‘Secret Annexe’ knew that she wrote; their clandestine visitors were also aware of it. They also knew approximately what she wrote, for sometimes Anne read aloud to them a scene from her diary, or an occasional story. Here and there in the darkness are flashes of light; but what was the whole like?

Anne wrote to Kitty:

Just imagine how interesting it would be if I were to publish a romance of the ‘Secret Annexe’. The title alone would be enough to make people think it was a detective story. But, seriously, it would seem quite funny ten years after the war if we Jews were to tell how we lived and what we ate and talked about here.

The ten years are long since past. Was Anne right? Is what she has told us so unbelievable? That child, and six of the seven persons who were in hiding with her, and another five million in addition were killed.

From this entry of March 29th, 1944, then, we know that Anne toyed with the idea of publishing her diary after the war. A broadcast by a representative of the Dutch Government-in-exile, which Anne had heard the night before on the Dutch News from London, suggested the notion to her, or confirmed a secret dream she had already cherished. Among Anne’s papers was found a list of fictitious names which she planned to use for the persons mentioned in the diary in case it were ever published. These fictitious names were employed in the version of the diary that was given to the world, and in order to avoid needless confusion I shall retain them in this book. But I shall also use false names or initials for my other witnesses, whom Anne did not know or did not mention. There are personal rights and private feelings which must be regarded. However, in order to ensure the authenticity of the statements recorded here, the full names and addresses of all my witnesses have been deposited with the legal representatives of the publishers Fischer Bücherei in Frankfurt.

Forty-two witnesses speak here. The fates of some will be related here, even though there are parts of their lives that seem to have nothing directly to do with Anne Frank. Nevertheless, these stories are not told for their own sake. I keep to Anne’s trail. But in many places this trail is so fragile and fugitive that it would fall apart and vanish if removed from the bit of ground that it has crossed.

There is a second reason for my telling about these others.

Fate led them to Anne from the most diverse directions. Their ways all came to a focus at a single point. Thereafter all radiated away, each toward its own destination. The focal point is the meeting with Anne Frank. These radii compose the world Anne saw when she looked around.

Forty-two of seventy-six witnesses, then. En route I was given the names of a seventy-seventh and a seventy-eighth. Probably they could have been located. But there was every reason to expect them to be unrewarding witnesses, and I did not seek them out. One of the two men was possibly the betrayer of Anne Frank; the other was indisputably one of the executioners. But Anne was only one of many victims, and the betrayer and executioner only two of many betrayers and many executioners. Some of these made their confessions in the courts. All of them gave the same testimony. What could these two have added? The gap in my account cannot be closed. Or, rather, in remaining open it is closed.

CHAPTER 2

The Beginning of the Trail and the Shadow

Before I set out on the trail of Anne Frank, I spoke to her father. He is a tall, spare man, highly intelligent, cultured, and well-educated, extremely modest and extremely kind. He survived the persecutions, but it is painful and difficult for him to talk on the subject, for he lost more than can be gained by mere survival.

The Franks were an old German-Jewish family. Otto Frank’s father, a businessman, came from Landau in the Palatinate. His mother’s family can be traced in the archives of Frankfurt back to the seventeenth century.

Otto Frank was born and grew up in Frankfurt am Main. He attended the Lessing Classical Secondary School, graduating with the Abitur (leaving-school certificate), and like his father, went into business. After the outbreak of World War I, he was assigned to an artillery company attached to the infantry. His unit consisted chiefly of surveyors and mathematicians, who as range-finders were stationed on the Western Front, in the vicinity of Cambrai, scene of many bloody, see-saw battles. Otto Frank participated in the great tank battle of Cambrai in November, 1917. His group was the first range-finding unit of the German Army to deal with the new British tanks.

The chief of the special unit to which Otto Frank was attached was named B. He is still living in Schwenningen. Frank speaks of this officer as a decent and enlightened man who handled his unit with the utmost fairness. In 1917 he proposed Frank as an officer candidate. With no background of either military training-school or special officer’s course, in 1918 Otto Frank was promoted in the field to the rank of lieutenant and transferred to the hard-pressed St Quentin sector of the Front.

After the war he settled down in Frankfurt as an independent businessman, specializing in banking and the promotion of proprietary goods. He married Edith Hollander of Aachen, who died in Auschwitz in 1945. In a photograph I saw her expressive profile. She had little resemblance to Anne.

In talking with me, Otto Frank did not say one word about his relationship to Germany or to Germans. I do not think he was silent in order to spare himself, or me. Rather, it was that no explanations were called for. He was born a Jew and a German, and as long as it was honourable to do so and possible for him to be a German, he served Germany. However, he was never a nationalist. Nationalism ran counter to the Frankfurt spirit. He had had God and fatherland; he was left with only God.

He said:

“I cannot recall ever having encountered an anti-Semite in my youth in Frankfurt. Certainly there were some, but I did not meet any of them. Nor did I meet any in the Army. Of course my superior was a democratic man who would have no officers’ mess or officers’ orderlies in his unit. Later on, when I was a lieutenant, I tried to treat my men in the same liberal way. I can recall only one occasion in my life when I saw a German snap to attention before me. Of course that did not happen until 1944.”

And an hour later this German delivered him to the Gestapo.

After his release from the Auschwitz concentration camp, Otto Frank attempted to reassemble the pieces of his old world. That proved impossible. Some few persons were living, but too many were missing. He did not give up the effort. Thus, he inserted an advertisement in a Frankfurt newspaper inquiring the whereabouts of Mrs Kati St, who had formerly been employed in his household in Frankfurt.

I visited Frau Kati in Höchst in June 1957. While she was explaining how her sister had seen the newspaper notice and had let her know of it, her husband looked among various papers on the bookshelf and produced a red folder labelled ‘Anne Frank’. He laid it before me on the table. Kati and her husband had collected everything that bore on the Franks – newspaper clippings, reviews of the Frankfurt performances of The Diary of Anne Frank, theatre tickets, an invitation to the celebration of Anne’s birthday on June 12th, 1957, in St Paul’s Church, an excerpt from Eugen Kogon’s speech on that occasion. But their collection dated from a time long before public memorials for Anne and stage performances; they had been gathering mementos since before the war. There were photographs and letters from Aachen and Amsterdam in the folder; there was also the note from Otto Frank written in February 1952 when they responded to his advertisement: ‘I am so wrought up, thinking of you, that I can say very little now. I will tell you the whole story when we see each other. Neither my wife nor the children are alive; all fell victim to the Nazis. I alone remain.’

Kati smiles and weeps all at once; there is no gulf between the smile which is meant for the stranger and the tears she weeps as she thinks of those who are gone. Kati is a pretty woman, probably around fifty. She beams whether she is smiling or weeping. Until her marriage in 1929 she was the mainstay of the Franks’ household. Even after marriage she frequently came to help out in case of illness or other emergencies. She was in the house at Margot’s birth, and watched Margot grow up; she was likewise in the house when Anne came into the world. But she remembers Margot more distinctly, and showed me pictures of the elder sister. Margot had always been the beauty of the two, as well as the gentle and well-behaved child. Out of the photograph a fair, regular-featured, almost angelic face gazed at me.

Kati could not say very much about Anne, whom she had known only as a small child. There was, she said, great commotion in the house when Anne was born. Mrs Frank went to hospital, and had a difficult delivery. But on June 12th, in the morning, Mr Frank telephoned Kati at last to say that it was another girl, and that all had gone well.

I told Kati that in the hospital records ‘the birth of a male child’ was recorded. Kati laughed at that. That showed how tired the nurse must have been after the long night, she exclaimed. Anne had not arrived until half past seven in the morning. But a boy, a boy? Kati smiled and shook her head. Oh no…

But then it occurred to her that after all there was something of the boy about Anne. Margot was always the little princess. She was neat and careful; except for her underclothes, she might have gone on wearing the same clothes for a week. It was as though dirt did not exist for her, Kati said. There was something almost unnatural about it, but dirt simply did not touch her; and Kati said, she always feared for this child, although she did not know why.

But Anne was the exact opposite of Margot. She had to be completely changed every day, sometimes twice a day. For example, one morning Kati found her sitting on the balcony in the rain, in the middle of a puddle, chortling with delight. A good scolding left the little girl unaffected. She did not even offer to get up out of the puddle. She wanted Kati to tell her a story right there and then, and it made no difference that Kati had no time. The story could be a short one, she said.

Kati lost patience. She picked Anne up, carried her into the nursery and set her firmly down on the table to change her clothes.

But then Kati remembers something else. She breaks her story to say:

“Above the nursery table hung a handsome lamp. It was very big, and Mr Frank had had it painted with animals. A regular zoo it was, and Anne would always look up at it. She had all sorts of stories about the animals.”

Kati returns to the photographs. She shows me one of Anne in a little white coat in front of a public building. (“God knows how long the coat stayed white that day” – Kati shakes her head.) Then Anne as a baby – and another of Anne as a baby, sitting on her grandmother’s lap. Mrs Frank is standing near...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- The Footsteps of Anne Frank

- Contents

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Author’s Note

- Dedication

- 1 The Focus and the Paths

- 2 The Beginning of the Trail and the Shadow

- 3 When We were Still in Normal Life

- 4 Ten Seconds

- 5 Deadlines and Top-Secret Orders

- 6 The Walk in the Rain

- 7 Marginal Notes

- 8 More Deadlines

- 9 The Final Solution

- 10 Visiting Hours after 9 am

- 11 The Journey into Night

- 12 The End of the Trail and the Moss

- 13 The Diary of Anne Frank

- Copyright