![]()

1

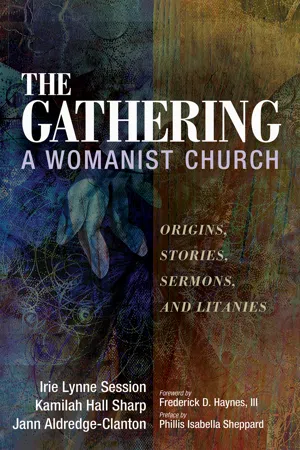

Defining a Womanist Church

A womanist church applies womanism and womanist theology to the creation of a faith community. The Gathering, A Womanist Church in Dallas, Texas, is unique as an embodiment of a womanist church. While other churches may draw from womanist theology, The Gathering uniquely applies womanism and womanist theology to the full life and worship of a church community. The Gathering is the only church founded and identified as a womanist church with “womanist” in the title.

Origins, Definitions, and Significance of Womanism and Womanist Theology

Womanism is rooted in Black women’s experiences of struggle, resistance to oppression, survival, and community building. The term “womanist” comes from Alice Walker, literary giant and activist, who is perhaps best known for her book and movie, The Color Purple. She said “womanist is to feminist as purple is to lavender.” Alice Walker coined the term “womanist” in her 1983 critically-acclaimed work, In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens: Womanist Prose.

The creation of this concept was a significant moment for women called to teach religion in academic institutions and to ministry in churches. The term “womanist” is derived from “womanish,” a Black folk expression of mothers to female children suggesting being grown and responsible. Therefore, womanist preachers seek to approach the homiletic text in a responsible manner, learning more than what’s on the surface, and doing the deep exegetical work of looking at the biblical text through a lens of liberation.

For Black women at the crossroads of academic institutions and the Black church, the 1980s was a time of self-definition. While the term “womanist” was introduced to the world in the 1980s, its meaning encompassed the lived experience of generations of Black women in America, who, like their biblical foremothers, were legally, socially, and even spiritually relegated to the edges of church and society. These women by mother wit, sheer will, and passionate determination charted their own course, rewriting definitions of what it means to be Black, female, and made in the image of God. With the Black Southern expression “you acting womanish,” mamas, grandmothers, aunties, church mothers, and other mothers confirmed, critiqued, and challenged their girl children to insure that they not only survived, but thrived in a world often configured to destroy their creativity, intelligence, and womanhood.

Definitions of womanism and womanist theology come from a variety of scholars, pastors, and authors. Women and men affirm the transformational significance of womanism.

Dr. Keri Day, currently serving as associate professor of constructive theology and African American religion at Princeton Theological Seminary, asserts that womanism gave her a language, a way of naming her own experience as a Black woman in a “society that does not privilege Black women’s knowledge production process, but rather culturally represents Black women as less or substandard or subhuman in a variety of ways.”

It was this devaluing of Black women that led to the creation of womanism, according to Rev. Dr. Renita J. Weems, Hebrew Bible scholar and co-pastor of Ray of Hope Community Church in Nashville: “You find yourself in a particular context where there are no Black women’s voices, no scholarship by Black women. You find yourself invisible; your voice is not wanted and not heard. The word ‘womanist’ just caught fire for all of us. It was different from ‘feminist.’ It was our word. It was what our mothers were calling us, meaning that we were sassy, meaning that we were courageous.” She explains that the word “womanist” comes from Black folk Southern culture, “meaning you are bold, you break boundaries, and you don’t mind doing that in order to accomplish what you have to accomplish.”

Rev. Dr. Teresa L. Fry Brown, professor of preaching at Candler School of Theology in Atlanta, Georgia, affirms the significance of Black women’s voices: “Black women do have voice, even in institutions that said we didn’t, that we were not in history books, that we didn’t have a place in church. It was through engagement over a period of time, meeting other women who were in little silos of institutions or in churches that I learned the importance of voice for all people.” She celebrates womanists as standing on their principles, articulating “the wit and wisdom of Black women” who came before them, and making way for women who will follow them.

Womanism, that centers Black women’s experience, is essential to the wholeness of church and society, proclaims Rev. Dr. Stacey M. Floyd-Thomas, associate professor of ethics and society at Vanderbilt University Divinity School in Nashville, Tennessee. Womanism is not only what the Black church needs but what America needs “if we’re truly going to embrace the best of who we are as a people who believe that we are all fearfully and wonderfully made and equally created by God.” The mission of womanism is “to make the church whole again and to bring the wisdom that is necessary for us all to be liberated and for none of us to be left behind.” She says that if it were not for “Black women, not only in the church, but in society at large, we wouldn’t have a keen sense of what freedom is.” She describes a womanist: “A womanist is wise. She’s radical, but she’s traditional. She’s self-loving, but she’s engaged. She’s subjective, but she’s communal. She’s redemptive, but she’s critical.”

Dr. James H. Cone, founder of Black liberation theology, celebrates ”womanist theology and Black woman” as “essential to the very life blood of what we mean by the Black church, the Black religious experience, the Black community.” He commends Black womanist theologians, such as Rev. Dr. Katie Cannon, Rev. Dr. Jacquelyn Grant, and Dr. Delores Williams, for contributing to his “constant development of Black liberation theology.”

Pastors also draw from womanist theology in developing sermons about race, gender, and class. Rev. Dr. Jacqueline J. Lewis, pastor of Middle Collegiate Church in New York City, states that she leads “with a womanist sensibility” in her multiracial, multicultural congregation. “We’re always thinking about how to story the gospel by any means necessary.” In her congregation “the conversations about race and ethnicity and difference and class take on all kinds of nuances,” she says. “I think especially of Alice Walker’s definition of ‘womanism’ as loving all people, understanding that our cousins are pink and beige and chocolate brown like me. That has been so important to me as I think about rehearsing the reign of God here on earth.”

Rev. Dr. Frederick D. Haynes, III, senior pastor of Friendship-West Baptist Church in Dallas, tells a story illustrating how womanist theology contributed to changes in his preaching: “I was up preaching, and I made a statement related to Sarah in Scripture. And one of my favorite womanist scholars texted me immediately, ‘You don’t want to say that. That is offensive. That is oppressive.’ The more I took a step back and looked at it, the more it dawned on me that I was a contributor, through that homiletical moment, to oppressing the dominant majority in the congregation. As the senior pastor, I don’t want to contribute to that oppression.” He gives womanism credit for bringing changes: “Womanism helps us reframe our language. Womanism h...