![]()

1 Origin, History, Composition and Processing

Sisir Mitra,1* Gabriela Fuentes,2 Arianna Chan,2 Amaranta Girón,2 Humberto Estrella,2 Francisco Espadas,2 Carlos Talavera,2 Jorge M. Santamaria,2

1Former Professor, Bidhan Chandra Krishi Viswavidyalaya, Mohanpur, West Bengal, India; 2Unidad de Biotecnología, Centro de Investigación Científica de Yucatán, Mérida, Yucatán, México

1.1 Origin and History

Carica papaya belongs to the family Caricaceae which consists of 34 species (and one formally named hybrid) and six genera (Carica, Jacaratia, Horovitzia, Jarilla, Vasconcellea and Cylicomorpha) (Carvalho and Renner, 2014). It has been suggested that the genus Carica was separated from its sister clade (Vasconcellea and Jacaratia) 25 million years ago, and since then it has had its own lineage (Carvalho and Renner, 2012; Pérez-Sarabia et al., 2017). The closest relatives to C. papaya are Jarilla and Horovitzia, both of which have a Mexican origin (Carvalho and Renner, 2014). The largest genus in the family Vasconcellea comprises 20 species and a naturally occurring hybrid, Vasconcellea × heilbornii (Badillo, 2000; Van Droogenbroeck et al., 2002). The centre of species diversity of the Vasconcellea genus is in north-western South America, especially Ecuador, Colombia and Peru. The genus Jacaratia comprises seven species, and is widespread in the lowlands of the Neotropics with only one species, Jacaratia chocoensis that is found at altitudes up to 1300 m in the Andes. Jarilla comprises three herbaceous species with perennial tubers that resprout annually during the wet season (Diaz-Luna and Lomeli-Sencion, 1992).

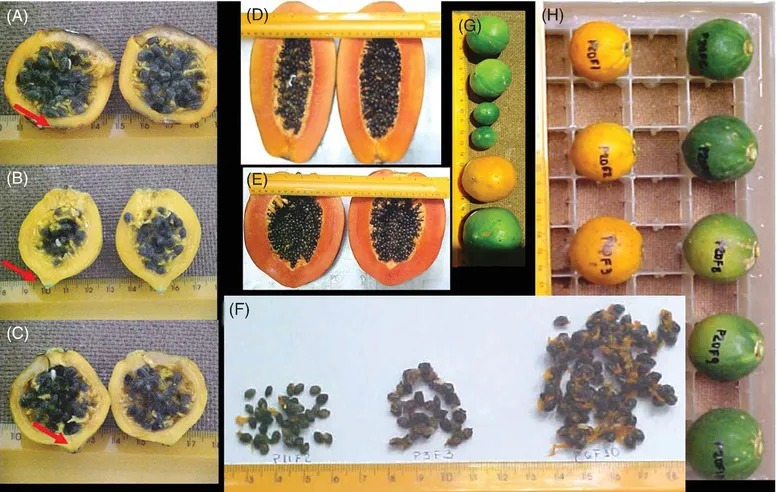

The first botanic record of C. papaya was made in 1753 by Linneaus (the Herbarium of the Missouri Botanical Garden – Tropicos.org, 2019) but this does not include historical botanic records deposited in local or national herbaria (Fernández et al., 2012). C. papaya L. is considered native to southern Mexico and Central America (Northern Mesoamerica) (Carvalho and Renner, 2012, 2014; Fuentes and Santamaria, 2014; Chávez-Pesqueira and Nuñez-Farfán, 2016). Wild papaya plants can be observed in populations distributed in several localities of the Mayan region (Yucatán and south of Mexico). Wild plants can be observed on the roadside and especially on the edges of roads and rural roads (Fig. 1.1). Wild papaya plants, native or non-domesticated, can be observed in ruderal vegetation (roadsides), and in successional vegetation or secondary vegetation. C. papaya wild plants are found with other plant species typical of the vegetation of the medium subperennifolia forest, subcaducifolia and deciduous or caducifolia low forest (dry forest) or secondary vegetation (G. Fuentes and J.M. Santamaria, personal observations; Flora de la Península de Yucatán – CICY, 2010). The wild populations that can be found in Yucatán normally have three or four individuals, but populations with up to 40 individuals can also be found. Wild populations of C. papaya can survive in adverse environments such as burning habitats, or in environments with temperatures above 40°C, or even in environments with prolonged drought (April and May in Yucatán, Mexico) (Alcocer, 2013; Girón, 2015; Chávez-Pesqueira and Nuñez-Farfán, 2016). In the dry season when other species such as trees and shrubs can be found without leaves, the wild papaya plants are found with leaves and flowers, and most of the papaya plants have a great number of fruits that survive until the rainy season in late June.

Interestingly, wild papaya plants have some characteristics that differ from those of papaya plants found in backyards of Yucatán towns. Wild plants cross pollinate, generating a very particular group with characteristics from wild and cultivated plants (feral populations). Semi-wild papaya plants can be found in backyards of many houses in the Mayan community. However, older people in the community who have traditional knowledge suggest a loss of traditional knowledge about the reproduction and sexuality of this species. This loss has implications for the conservation of the germplasm of this species (Moo, 2015). Two characteristics of these fruits are: (i) fruits of larger size than those from wild plants; and (ii) the fact that it is possible to find fruits that are borne on hermaphrodite plants. On the contrary in wild C. papaya populations, fruits are rounded and small and only female and male plants are found.

An isozyme analysis of numerous papaya accessions, while revealing limited genetic diversity, showed that wild papaya plants from Yucatán, Belize, Guatemala and Honduras were more related to each other than to domesticated plants from the same region (Morshidi et al., 1995).

The origin of C. papaya is in the north of Mesoamerica and the later domestication and cultivation also involved the adaptation of wild papaya to climate change over time (Zizumbo-Villarreal et al., 2014). The domestication in many forms by different groups in different environments expanded its genetic diversity. C. papaya is found in different environments, records of papaya plants (herbarium data) can be found from 1000 to 1981 m above sea level (masl), from the Mexican states of Chiapas, Guerrero, Oaxaca and Veracruz (3% of records). However, a large number of records are located at low elevations, between 0 and 200 masl (41% of records). The states with a high number of records (herbarium samples) are Veracruz (21%), Chiapas (20%), Oaxaca (18%), Campeche (9%), Tabasco (6%), Quintana Roo (6%) and Yucatán (5%) (Herbario Nacional de México, UNAM, 2019). On the other hand, it is interesting that wild C. papaya plants are dioecious (with female and male plants), and pollen must be transported by a vector and/or by air to carry out pollination. There are a lot of male plants (Y) in the Yucatán vegetation. In Yucatán it is possible to find wild C. papaya plants bearing very small rounded fruits (2–3 cm long).

Wild papaya plants should be a great reservoir of potential genes that may have been ‘lost’ (not expressed or repressed) during the domestication process. These wild plants are in contact with adverse physical environmental conditions (abiotic agents) and with other animals (biotic agents), and their genetic base is broadened in order to survive these conditions (Fig. 1.2). By having the genome of a commercial papaya sequenced (Ming et al., 2008), it is very interesting to know the genome of a wild papaya.

Even if 100% of national requirements are currently satisfied with domestic production in relation to the varieties or types that are grown, one of the great challenges has been to diversify the species (i.e. to generate varieties or types of papaya that can already either meet demands or offer products for particular needs). For example, fruit with a high content of lycopene versus a fruit with a high content of β-carotene or fruits that are about the size of a mango that could be consumed individually by a single person or a fruit that can be used as vector of vaccines.

C. papaya is thus one of the genetic resources provided by Mexico and Central America to the world. The papaya (pitzáhuac or chichihualtzapotl in Nahuatl), that can be translated as ‘zapotenodriza’ in Spanish, is a fruit native to Mexico and Central America (Mesoameric zone) that has been used since the pre-Hispanic period (Vargas, 2014). The Spanish distributed this fruit around the world (particularly in Asia and Europe) since the 16th century, so that it is now known in most places around the world (González and del Amo, 2012).

In pre-Hispanic México, the main plants included in the Mesoamerican diet were: nopales, quelites, sweet potatoes, algae, mushrooms, tamarindo, capulines, tejocotes, jicama, chirimoya, guanabana, mesquite, sunflower, guava, mamey, papaya, jicama, pineapple, banana, zapote, as well as grasshoppers and maguey worms, among others (Giordano, 2018). C. papaya is a fruit associated with the traditional agriculture of the lowland Maya that currently have wild populations or wild ancestors within the Mayan area (Colunga-García and Zizumbo-Villareal, 2004; González and del Amo, 2012).

1.2 Composition and Uses

It seems that papaya is a crop with a lot of potential as many countries are interested in consuming papaya fruit. This interest may increase as the knowledge of its great benefits for nutrition and health may increase. F...