![]()

1. Newton’s Law

Patty Newton was convinced the serial killer had broken into her house and walked around upstairs as she lay sleeping — knowing all the while that her police-chief husband was away from home. It was 1989 and Allan Legere had murdered five people and was hiding out from authorities in the forests and small towns of the Miramichi in northeast New Brunswick. And where better to hide, Patty reasoned later, than in the backyard of the local police chief, where no one would think of looking?

The Newtons lived in Newcastle, one of the scattering of towns in the heavily forested Miramichi. Like many of her neighbours, as the Legere terror spread, Patty had acquired a pistol, which she hated to have in the house and hoped never to have to use. But her husband, Dan Newton, was often out on patrols all night and it made sense.

This time, however, he had gone to a father-daughter event with their daughter, Peggy, leaving their teenage son Chris with her. During the evening, Dan’s parents had dropped by and decided to stay the night. At one point in the night Patty woke up to the dogs barking and heard someone scampering down the back stairs and out the door. “I’ll give Chris hell in the morning,” she thought to herself and went back to sleep.

The next morning, young Chris Newton insisted he had not been up in the night and had not raced down the stairs. One of the family dogs rushed over to a backyard bush and was barking like mad. Patty called one of the fellows on the police force to come and look in the backyard, and, yes, it was possible the killer had spent the night there — someone had hidden in the bush. Soon police helicopters were hovering over the neighbourhood. The memory sends a chill through her to this day, as Patty sits today at her kitchen table in a village near Moncton.

The Miramichi region produces rivers teeming with salmon, fishing camps of the well-to-do, forests of timber, the haunting novels of David Adams Richards and, for a horrible moment in the late 1980s, one of Canada’s most sadistic serial killers. The ordeal had begun when, along with a couple of low-life pals, Legere had beaten a shopkeeper to death. He had been sent to prison, but cunningly escaped from a hospital where he had been sent for an ear infection He went on to kill four more people — a couple of middle-aged sisters, an elderly woman and a priest. Leaving behind a trail of murder, rape and torture, for 201 days he stalked the woods of northern New Brunswick, earning the name the Monster of the Miramichi.

The nightmare dominated the life of the Newton family, with their dining room table becoming the site of regular nightly meetings of police officers, working with Dan on the desperate manhunt, with Chris looking on with interest as the senior cops planned their strategies.

Legere was finally recaptured on November 24, 1989, following a failed carjacking — he picked the wrong car, this one driven by an off-duty policewoman who managed to escape his clutches and alert her colleagues. “You could hear the whole town take a big sigh of relief,” says Patty, a warm and witty woman who was later divorced from Dan Newton and remarried.

It was a nightmarish period in what was otherwise a carefree life growing up in the Miramichi for the Newton kids, Peggy and Chris. It was a reminder that the Miramichi was a thinly populated rural region where a murderer could hide for weeks, but it was also, in better times, an idyllic land where a young Chris Newton could grow up in the outdoors, build tree forts, ride bicycles, tinker with gadgets — room to grow into a young man with a sense of the possibilities life had to offer.

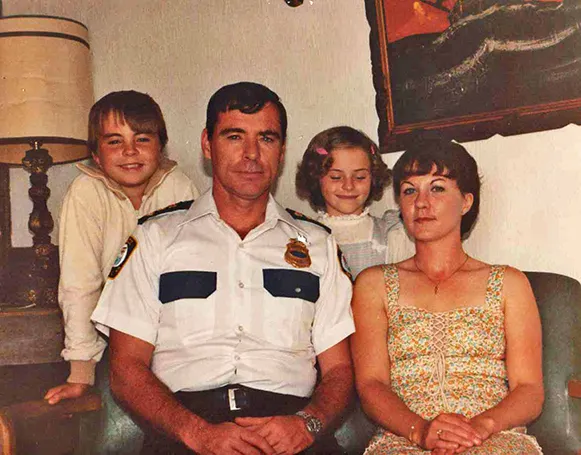

The Newton family circa 1980: Chris, Dan, Peggy and Patty

(Courtesy of Patty Phillips)

Some people in New Brunswick’s tech industry speculate that the example of his policeman father may explain why Chris became interested in catching bad guys, whether it was malicious forces invading university networks or predators on the internet. Sometimes the solutions he devised ended up being used in other ways than intended, but Chris was always a guy who believed in rooting out bad actors. And Chris idolized his policeman father.

The Newtons lived an itinerant life as Dan followed his career — from Middleton in the Annapolis Valley where Chris was born, to Nackawic, a little riverside community west of Fredericton, and then to his biggest posting, Newcastle, today part of the amalgamated urban-rural city of Miramichi. It was a traditional family — Dan worked hard and Patty was always busy raising the kids, although she would find a welcome diversion in painting, and later she became a skilled computer graphic artist.

Chris Newton grew up with a rambling curiosity about how things worked, and a great visual sense like his mom, with the ability to express complex ideas in pictures and graphics. Early on, he was a fix-it kid. His mother remembers being in the house when she became aware that four-year-old Chris was being very quiet. She went down to the basement rec room to check on him. He had a sports-car pedal car up on blocks, completely taken apart, with the little kid lying on his back with his dad’s tools. Cars became a passion for life.

So was technology. When Chris hit his early teens, he got his own home computer, one of the early ones, a Commodore. He was no whiz in school, but the computer opened a vast world of information. Suddenly this book-averse kid was reading computer manuals and looking up arcane information on the just-forming internet.

This was the era of a visionary New Brunswick premier, Frank McKenna, who pushed a bold plan to wire the province, bringing broadband into rural homes. McKenna had practised law in the Miramichi and represented the local riding of Chatham in the legislature. Chris Newton is a product of the Miramichi but also of the McKenna Revolution that transformed New Brunswick from a backwater to a knowledge economy pioneer. Another beneficiary of the McKenna revolution was Jody Glidden, a Miramichi Valley High School mate of Newton, who was able to buy his first computer with the help of a government subsidy introduced at the time.

Glidden later became a founder of multiple high-tech startups. He remembers Newton as a shy kid in school, whom he would never expect to be a technology leader or a businessperson. Chris was your classic quiet classmate from high school, the late bloomer who fades into the background, until 20 years later when his picture appears in the newspaper and you say, “I never dreamed he would be so successful.” In Miramichi, in the 1980s, Newton was living the typical boy’s life — hockey, air cadets and senior prom. He was the definition of a good kid who could be trusted to go out on teen excursions to the big bad city of Moncton without getting into trouble.

When he graduated from high school, Newton went to UNB, two hours away in Fredericton, where he enrolled in the top-notch computer science program, a leader in Canada. In 1968, UNB had launched the first computer science department in the country. (UNB has a second smaller campus in Saint John.) Newton liked the courses, and he was naturally curious, but not a top student — he struggled in math, particularly calculus, and wonders to this day why anyone needs it. But he loved fixing things, he read deeply in science, and he spent his time visualizing how things worked, how patterns were formed and how information flowed.

His most formative university experience was getting to know another couple of kids with similar backgrounds and inclinations. Sandy Bird hailed from Fredericton where his dad and his family ran an auto-parts shop on the north side of the river, Central Auto Parts, where the sign over the door says, “If you don’t see it, please ask.” His mother helped run her own family’s fuel-distribution business. Sandy was a small guy, compactly built like Chris, engaging and outgoing but with a way of squinting his eyes that suggested a coiled intensity.

There was also Dwight Spencer, slightly older, a big fellow with an open, friendly face who came from a family that worked in forestry in Chipman, an hour northeast of “Freddy” in New Brunswick’s interior woods. Chipman is a town dominated by a Shoppers Drug Mart, a couple of supermarkets and a vast J.D. Irving woodlands operation and sawmill. Dwight’s father had worked as a contractor for the ubiquitous Irvings.

The guys were all crazy about computers, but they were also passionate gearheads — they loved to get their heads inside a car engine. They had no money, but life was a lot of fun. And to support their studies they all took on tech jobs around the university. Chris and Dwight both worked at the UNB Computing Centre, the heart of the university network; Dwight went to the Harriet Irving Library; Sandy spent time at both, and in the arts faculty. “It became this weird triangle where we are all trading jobs around the university,” Dwight recalls. And they tinkered. At one point, the three of them took down the university network. And Sandy and Chris roomed together for a while.

It’s a reminder of how often the world’s technology advances occurred because someone met someone else in school — what if Microsoft co-founders Paul Allen and Bill Gates had not met at a Seattle high school, or Google’s Larry Page had not run into Sergey Brin at Stanford? Chris met Sandy and Dwight and they got along. What is amazing is they kept getting along — and in the laid-back chemistry of New Brunswick, they get along well to this day. Despite disease, heartache and corporate breakups, their friendship remained strong. They still talk often.

These were blue-collar kids, not showered with money or toys. They could use the extra money from a university job while they continued to study. Chris liked that he didn’t need to work in some burger-flipping joint but could make income from a job where he was naturally engaged, and would know when new opportunities popped up. All the time, they figured they would eventually graduate — although for Dwight, the object was never graduation but a way to gain independence and not rely on his parents’ support. But for all of them graduation would never happen. Life would get in the way.

Chris was hired as a network analyst even though he didn’t strictly qualify in terms of education yet — he had no degree. But that job put him on the ground floor of the internet, as it moved from the gee-whiz stage to the serious-business-possibility stage. It was a halcyon age for tech geeks because the challenges were so new and broad. At the same time as the UNB Three were working away, Page and Brin, also in their early 20s, were playing around with the beginning of Google. It was a few years before Mark Zuckerberg would set up a social network at Harvard so that children of the establishment could hook up.

Newton was also fortunate to be a part of UNB and its computer science program, a true community of scholars and innovators. The early pioneers in the computer science faculty and the UNB Computing Centre — people like Dana Wasson and Dave Macneil — had created something that had a reputation far beyond the province. Newton took courses from Jane Fritz, who was dedicated to her smart and slightly obsessive students. Macneil and his colleagues in the Computing Centre, Peter Jacobs and Greg Sprague, created an open and comfortable working environment. And there was Ali Ghorbani, a brilliant Iranian-born academic and entrepreneur in his own right, who would later undertake important research for Chris Newton’s real-world applications.

Chris Newton with his first car, a sporty Miata (Courtesy of Patty Phillips)

Newton was cloistered in a closet-sized office, along a dark corridor with putrid green institutional walls. That was where he would discover one of his lifetime credos: every pain point is an opportunity. It became Newton’s Law, circa 1998: great ideas usually come not from dreamy futuristic navel-gazing but from solving a painful problem for somebody. And UNB certainly had a pain point.

It could be narrowed down to one little white laptop computer that was the fragile front-line defence in UNB’s flailing efforts to combat cybersecurity breaches. Newton would watch his colleagues in the Computing Centre as they coped with this new phenomenon — delicate networks would buckle under denial-of-service attacks in which hackers would bombard the system with hundreds of millions of data units called packets. It was as if thousands of letters were suddenly dumped into a country-road mailbox with a ten-letter capacity.

As the network shut down under the weight of this inundation, the Computing Centre would be deluged with angry messages from students, teachers, administration. It was very stressful.

Newton recalls that “the guys in the networking group had one tool for when things go wrong, a program called Sniffer, which ran on this little white laptop.” Someone would open this special laptop and plug the network cable from the laptop into the network switches — and the laptop would freeze.

There followed a seeming eternity of pulling cables and inserting plugs, waiting until the laptop calmed down and started to respond, while the whole university stewed. “We’re talking a big university, a lot of students and very high-speed connections and this laptop had no hope,” Newton recalls.

Newton got to thinking: “Wouldn’t it be better if we had something that looks at not single packets but at data flows? Instead of looking at millions of individual packets, look at a single data record that says ‘this machine sent 400 million packets to this machine and that is one flow.’” He looked around and saw nothing available, so he started coding a solution.

Newton speaks in bursts of gee-whiz enthusiasm — more Richie from Happy Days than the nerdy guys from The Big Bang Theory. Everyone is “super-busy” or “super-smart,” or to sum things up, it was “all that jazz” — all interspersed with the occasional mild profanity. The unfiltered vocabulary masks a sharply inquisitive mind that ranges far afield, and a wry sense of humour, with low-key observations of the passing parade of life.

The Computing Centre was fortunate to have a number of sage operators who recognized his intelligence and didn’t feel threatened by the kid down the dark hall. Macneil, a kindly bearded man, started noticing what Newton was doing and gave him $1,800 to buy a server for his office. Jacobs gave him a network tap so he could look at data across the university.

“You would never get away with that today,” Newton marvels. “I never even thought that everybody’s emails were going across in front of my eyes. I didn’t even think to look at them. Today, I’d think ‘Holy shit, I could have got in a lot of trouble even if I accidentally recorded stuff.’”

Macneil, who split his duties among teaching, research and administration, was spending a lot of time with the young student-employee, checking in with him every morning, after Chris had spent the night writing code. Newton found Macneil’s interest both scary and thrilling. “He made me nervous because every morning at eight-thirty, he came in my office with a fresh cup of coffee and asked ‘what did you do last night?’ I would show him the stuff. Then he’d come and get me at coffee and lunch break and we would talk through it.

“It was just weird. I’m super-young and Dave was the head of the department and widely respected worldwide. He’d go to conferences on how to introduce high-speed internet and he was spending time with little old me in the coffee room. A big part of what was driving me to come up with cool stuff was Dave.” (Dave Macneil died in late 2018, just as I was beginning research on this book, a huge loss to New Brunswick and computer science worldwide.)

“If that one little pain point h...