ONE

IMAGE

ON THE SELF-REPRESENTATION IN THE MUSIC

I begin this chapter in 1967, the year of one of the twentieth century’s most successful world fairs: Expo 67 in Montréal. It was also the year Leonard Cohen launched himself on the international scene as a singer with his first album, Songs of Leonard Cohen. It goes without saying that the construction of a public image had also been an integral part of his authorship, but 1967 was a turning point in more than one respect. From then on Cohen would have to express himself within the context of popular culture, where the relationship between maker and work is far more obvious than it is on the literary circuit. In those years, pop music was almost exclusively covered in the (non-academic) music press, where the dominant formats of the review and the interview gave musicians a platform to promote themselves and explain their work. Gigs, too, enabled them to flesh out their image through direct contact with audiences. The release of live albums (both official and bootleg) shows that these have a greater impact than the traditional poetry evenings and literary happenings in writing circles. In that sense Cohen’s unconventional performances as a writer, which carried a whiff of stand-up comedy, had already been rubbing up against the popular circuit, not unlike the American beat poets who popped up in talk shows and magazines such as Playboy.

At least as important was the new audience, international and anonymous, to whom Cohen was still a complete unknown. Songs of Leonard Cohen was released in the United States, but thanks to some influential mediators1 Cohen soon gained a foothold in Europe. But for this European audience the song lyrics were not as accessible as the literary work had been for his Canadian readership: not all listeners mastered the (often well-wrought) English, nor were the song lyrics readily available in printed format, not even on the first LPS. Journalists and critics in Europe were asked to round out their reviews with transcripts and translations of these lyrics. Jacques Vassal recalls the situation in France: “and the way we […] strained our ears to copy the texts bit by bit. Then came Cohen’s first ‘songbook,’ which had been imported. Here, finally, was our chance to verify that we had understood everything, and to learn to accompany those songs on guitar” (Mus 2018a). The lyrics are obviously only one part of a broader musical experience, and a lack of understanding can actually be productive. Translation scholar Susam-Sarajeva suggests that “non-translation in the case of music may allow the imagination more leeway” (2008, 192). This imagination crystallizes in an overall experience, as the interplay of word, image, and sound.

All these dimensions must be considered in an analysis of pop music. This is something Vicky Broackes (2018), senior curator at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, is acutely aware of, having curated several successful exhibitions on the likes of David Bowie and Pink Floyd that cater to a growing trend in the museum world. The traditional role of the viewer as one who passively consumes exhibits was systematically swapped for a more active museum experience revolving around immersion and interactivity. This idea of “experiencing knowledge” also informed the scenography of the Cohen exhibition A Crack in Everything. Although its primary focus was the impact of Cohen’s oeuvre on international artists who had assimilated his universe in their own artistic practice, for many the first room was the highlight of the exhibition. This imposing space was set up as a kind of experiential chamber aimed at visualizing Cohen’s artistry: a selection of video excerpts in which Cohen delivered the same song live at different moments in his career was projected simultaneously on to the high walls. This was without a doubt the room where visitors spent the longest and happily immersed themselves, without additional explanation either on the wall or via audio guide, in Leonard Cohen’s world, which is mainly a world of sound and vision. The exhibition makers appealed to a sense of recognition and capitalized on the direct expression made possible by the available audio-visual material and technology.2

In the same way, Cohen’s publishers were aware of the communicative power of imagery at an early stage. When his poetry was first published in the United States, in 1965, the poems from The Spice-Box of Earth were complemented with a series of drawings. In later collections, such as Book of Longing and The Flame, Cohen’s drawings would be printed alongside the poems, and at recent gigs images would occasionally be projected onto the backdrop. The hundreds of portrait photos of the man with the “lines in his face,” and even the lettering of his first and last name, have become equally iconic. Obviously, these graphical elements all help direct our reading. An analysis of Cohen’s international reception should therefore consider the interaction between a range of semiotic dispositifs, all the more so since Cohen’s artistic practice has developed in various directions: his literary and musical work are well known, but his output as a draftsman, dramaturge, actor, and even translator have been overlooked in the existing literature.

In this chapter I would like to take a closer look at one aspect of this practice and its reception, in particular the impact of images on (the perception of) the musical oeuvre. I shall do so by comparing the album covers and the music. It is correct to say that in today’s music world, the idea of a discrete album is much less of a unifying principle than it used to be. Individual songs are sent into the world via all manner of music websites and streaming services without necessarily being part of a greater whole. Likewise, a carefully orchestrated publicity campaign circulated a few select songs ahead of the release of Cohen’s final albums. But that does not alter the fact that up to and including You Want It Darker the albums were always released as independent entities. Another major difference between the 1960s and today is the formats on which the music is disseminated. For a long time the vinyl LP (which is gaining traction again these days) was the prime format until it was replaced by the CD. One of the differences between the two was their size. The LP may have come in different editions, but it was always larger than the CD. This meant that the covers looked more impressive and served a dual purpose. They observed a commercial logic (attracting the potential buyer’s attention) while at the same time creating a visual encapsulation of the new album. They are, each one of them, powerful images, consumed at a glance and thus literal representations of the art. The music is captured in advance in a way that appeals to a wide audience.

CAVEAT EMPTOR

READER AND LISTENER, BEWARE!

Did Leonard Cohen wonder in December 1967 how much control he would have over his new international career as a singer-songwriter? A few months earlier he had walked off stage after playing a few chords of “Suzanne.” Having lapped up his shy appearance, the audience encouraged him to carry on playing, which he eventually did. The thirty-three-year-old Canadian, considered by many to be too old to be making his musical debut, must have thought about the charms of naïveté: a precious quality almost always remarked on by others. In interviews he frequently let on that he had no truck with enigmatic figures, yet he was all too aware of possessing such a talent himself: “I used to be a good hypnotist,” he once told a journalist (Brusq [1996] 2009). His mysterious utterance appeared to evoke Lawrence Breavman, the protagonist from The Favourite Game, who had taught himself the art of hypnosis to win over women.

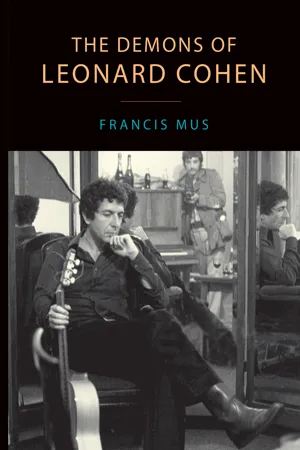

Be that as it may, the cover of the first LP displayed a disarming simplicity. This does not look like a carefully constructed image at all. Maybe the cover had not been given much thought (which is highly unlikely). Maybe it did not matter much (less than in our current visual culture perhaps). Or maybe the use of a dark, sepia-coloured passport photo on a jet-black background was a deliberate strategy. We see a shy young man, staring intently into the lens with a determined look on his face. The title, Songs of Leonard Cohen, likewise bespeaks simplicity. No great proclamation, just an almost redundant statement, which serves to herald a new name in a world in which the likes of Bob Dylan (Blonde on Blonde), the Beach Boys (Pet Sounds), the Rolling Stones (Aftermath), and The Beatles (Revolver) were already well established. Although Cohen would always have his name on the cover, he would never again use it in an album title. What is more, his name would never again so unequivocally evoke the image of a young but celebrated writer from Canada who wanted to make music too.

But even on this “naive” cover, the form is carefully considered. The simplicity of the front is complemented by a remarkable picture on the back—a so-called anima sola, a female figure depicted in the flames of purgatory. The solemn style and the religious content of the drawing lend the album a serious aura and establish a connection with the literary work, in which religiosity, femininity, and the searing power of love had figured prominently for some time. Several months after the release of Songs of Leonard Cohen an article appeared in the New York Times: “Disks Wear Art on Their Sleeves to Woo Buyers.” The journalist concludes that something is afoot. He talks about a “revolution” in album-cover design, with copious experimentation with various art forms (painting, sculpture, photography) and no clear rules, except a duty to be experimental. “The static art of romantic mood is out.” Like Bob Dylan, Leonard Cohen proves to be an exception: “Leonard Cohen, the folk singer, insisted on taking his own picture for a Columbia album. He went to an amusement arcade, spent a quarter in the automatic photo machine, and brought the result back as the cover picture” (Shepard 1968). Two years previously, Cohen himself had warned his readers that such naive imagery should always be approached with the necessary circumspection. Released in 1965, Ladies and Gentlemen… Mr. Leonard Cohen is one of the first documentaries dedicated to him. Cohen is filmed during performances, while meeting friends, and even in the hotel room where he was staying at the time. On the bathroom tiles he writes “CAVEAT EMPTOR” in block letters, which is to say that the viewer is warned, as he is merely watching the constructed image of a writer. On the inner sleeve of the first LP he again alludes to the fact that it is hard to differentiate between semblance and being when he tells the listeners: “The songs preferred to retreat behind a veil of satire.” In short, it is not just the singer who struggles with his image. Even the (personified) tracks find it hard to come to the fore. He was to repeat his caveat emptor trick several times. In a songbook from 1969, with the same title as his first album, a note he jotted in the margins of the introduction made it into the printed version: “This is pure fantasy. Never heard of the man mentioned here. All good things. Leonard” (Kloman 1969). And in 1975, on his Best Of, he included a photo taken in the hotel bathroom mirror, as if he would only be pictured in an indirect way.

Songs of Leonard Cohen (1967)

Michael Ondaatje remembered Cohen’s warning: in 1970 he noted that Cohen pursues some measure of sincerity not in the media but in his performances, especially when he improvises and engages in spontaneous dialogue with his audience. The interaction at such live shows allows him to continuously adjust his image, depending on who is sitting or standing before him and what reactions he receives. That dialogue is lost when the listener at home or in the shop sees an album with just a single captivating image. Let us therefore assume that his album covers are not at all random. The question then is: What do they communicate? What story do they tell us when we line them up? How can Leonard Cohen’s fifty-year musical career be reconstructed using some twenty carefully chosen illustrations through which he has tried to shape his image? It is certainly striking to see that a photo of Cohen graces the front cover of just about every ...