![]()

1 The rise of the cluster concept in regional analysis and policy

A critical assessment

Bjørn Asheim, Philip Cooke and Ron Martin

Introduction: the cluster craze

Over the past two decades or so there has been a veritable flood of interest, within economic geography, economics, and business studies, in industrial localization: the observed tendency for many industries to form specialized concentrations in particular locations. Industrial localization of course is nothing new. It was a key characteristic feature of nineteenth-century industrialization in Europe, the United States, and elsewhere. But for much of the twentieth century, in the face of major shifts in industrial structure, the rise of mass production methods, and the ascendancy of the large, integrated firm, many of these former localized concentrations of specialized activities went into decline and a rather different, more geographically dispersed, pattern of production became the main basis of economic growth: what has commonly come to be known as the transition from Fordism to post-Fordism (Piore and Sabel, 1984). In addition, for some commentators, since the beginning of the 1980s, the accelerating movement towards a globalized, information-technology driven economy has further eroded the significance of location and spatial proximity for business performance and success (O’Brien, 1992; Cairncross, 1997; Gray, 1998; Reich, 2001).

However, reality seems to point in the opposite direction: globalization and technological change appear to be promoting rather than reducing the importance of location in the organization of economic life. According to many observers the past two decades or so have witnessed the emergence of new localized production systems of specialized industrial agglomerations, as part of a more general ‘resurgence’ of regions and cities as the loci of contemporary economic development and governance (see, for example, Sabel, 1989; Storper, 1995, 1997; Krugman, 1997; Porter, 1998; Scott, 1998, 2001; Morgan, 2004). Thus as the highly influential business economist Michael Porter puts it (1998, p. 90):

In a global economy – which boasts rapid transportation, high-speed communications, accessible markets – one would expect location to diminish in importance. But the opposite is true. The enduring competitive advantages in a global economy are often heavily localized, arising from concentrations of highly specialized skills, knowledge, institutions, rivalry, related businesses, and sophisticated customers.

At the same time, these observers argue, increasing global integration itself leads to heightened regional and local specialization, as falling transport costs and trade barriers allow firms to agglomerate with other similar firms in order to benefit from local external economies of scale (Krugman, 1991; Fujita, Krugman, Venables, 1999; Brackman, Garretsen and Marrewijk, 2001; Baldwin et al., 2003), which in their turn are thought to raise local endogenous innovation and productivity growth (see Martin and Sunley, 1998). For these and other related reasons, it has become fashionable within certain academic circles to talk of the ‘localization of the world economy’ (Krugman, 1997) and the rise of a ‘global mosaic of regional economies’ (Scott, 1998). Further, the definition of post-Fordist economies as ‘learning economies’, in which innovation is a socially and territorially embedded, interactive learning process (Lundvall and Johnson, 1994), also emphasizes the importance of localized industrial agglomerations, in this instance as providing the best context for the promotion of knowledge-intensive innovative firms (Asheim, 1999; Cooke, 2001; Maskell, 2001).

These localized concentrations of specialized activity take many different forms, and numerous neologisms have been coined in attempt to capture their salient features. The industrial districts of the so-called Third Italy were one of the earliest prominent types to attract discussion (Brusco, 1989, 1990; Becattini, 1989, 1990; Asheim, 2000; Paniccia, 2002). Meanwhile in California, Allen Scott began to highlight the rise of new industrial spaces (Scott, 1988). Others have preferred to talk of local production systems (Crouch et al., 2001). Still others, focusing on localized agglomerations of high-technology activity, have variously used such terms as local high-tech milieux (Keeble and Wilkinson, 2000), local and regional innovation systems (Asheim and Gertler, 2005; Cooke, 1998, 2001), or even learning regions (Asheim, 1996, 2001; Florida, 1995; Morgan, 1997).

However, probably the most influential neologism to have swept through the academic and policy discussions of economic localization is Michael Porter’s notion of industrial or business clusters. According to Porter (1998, p. 8),

Clusters are a prominent feature of the landscape of every advanced economy, cluster formation is an essential ingredient of economic development. Clusters offer a new way to think about economies and economic development.

Porter (1998, p. 197) defines clusters as

Geographical concentrations of interconnected companies, specialized suppliers, service providers, firms in related industries, associated institutions (for example universities, standards agencies, and trade associations) in particular fields that compete but also co-operate.

There are two core elements in his definition. First, the firms in a cluster are linked in some way. Clusters are composed of interconnected firms and associated institutions linked by commonalities and complementarities. The links are both vertical (buying and selling chains) and horizontal (complementary products and services, the use of similar inputs, technologies, labour, etc.). Moreover, most of these linkages, he argues, involve social relationships or networks that produce benefits for the firms involved. The second key feature is that of geographical proximity: clusters are spatially localized concentrations of interlinked firms. Co-location encourages the formation of, and enhances the value-creating benefits arising from, networks of direct and indirect interaction between firms.

Over the past decade the cluster concept has become the standard term in the field. Moreover, Porter has promoted the idea of clusters not only as an analytical concept but also as a key policy tool. As the celebrated architect and promoter of the idea, Porter himself has been consulted by policy-makers the world over to help them identify their nation’s, region’s, or city’s key business clusters or to receive his advice on how to promote them. From the OECD, and the World Bank, to national governments (such as the UK, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Portugal, New Zealand), to regional development agencies (such as the new Regional Development Agencies in the UK), to local city governments (including various US states), policy-makers at all levels have become eager to promote local business clusters. Nor has this policy interest been confined to the advanced economies: cluster policies are being adopted enthusiastically also in an expanding array of developing countries (see Doeringer and Terkla, 1996; World Bank, 2000). Clusters, it seems, have become a worldwide craze, a sort of academic policy fashion item (see Martin and Sunley, 2003).

The more so because the concept has become increasingly associated with the so-called ‘knowledge economy’, or what some have labelled the ‘New Economy’. Norton (2001), for example, argues that the global leadership of the US in the New Economy derives precisely from the growth there of a number of large, dynamic clusters or localized concentrations of innovative entrepreneurialism. Porter himself has headed a major policy-driven research programme to ‘develop a definitive framework to evaluate cluster development and innovative performance at the regional level’ in the US in order to identify the ‘best practices’ that can then be used ‘to foster clusters of innovation in regions across the country’ (Porter and Ackerman, 2001; Porter and van Opstal, 2001). In the UK, the promotion of clusters, especially of biotechnology, ICT, and so-called ‘creative industries’ (such as media, design, fashion, film and other cultural products sectors), has figured prominently in central government policy and the economic strategies of the regional development agencies. Likewise, the OECD (1999, 2001) sees innovative clusters as the drivers of national economic growth, as a key policy tool for boosting national competitiveness. Clusters, it seems, have become the new policy panacea.

Our purpose in the remainder of this introductory chapter is to provide a synoptic reflective overview of the cluster concept, its relationship to other related ideas in economic geography and economics, the strengths and weaknesses of the concept, and its grip on regional development policy. This then sets the scene for the more focused and detailed essays that follow. The aim of the book is to take stock, in a constructively critical way, of the scope and limits of the concept, as both an analytical and a prescriptive tool.

Conceptualizing clusters

As mentioned above, Porter’s cluster concept is one of a number of different streams of literature concerned with the phenomenon of economic localization. It is useful, therefore, to situate his cluster idea within this wider intellectual context. In fact the localization of economic activity has become a central topic of interest in several different fields of economics and economic geography.

At the time of its somewhat opportunistic discovery in the 1990s by the business school fraternity, and by Michael Porter at the Harvard Business School in particular, the study of ‘industrial district formation’ (Becattini, 2001) or ‘districtualization’ processes as they are perhaps less elegantly called (Varaldo and Ferrucci, 1996; Lazzeretti, 2003), was already well under way amongst several Italian economists, with regional scientists and economic geographers of a heterodox bent as unofficial observers (Cooke and Da Rosa Pires, 1985; Scott, 1988). The publication of a significant synthesis of the Neo-Marshallian Italian research by Piore and Sabel (1984), also from Cambridge, Massachusetts, not Harvard but MIT, with its prognosis of a ‘second industrial divide’ marking a shift from mass production into an era of neo-craft ‘flexible specialization’ characteristic of industrial districts, gave further legitimacy to research in this field. Of particular importance and value in bridging the features of Italian neo-craft production in industrial districts and high technology production in modern industrial spaces was Saxenian’s (1994) anatomization and comparison of Silicon Valley’s success, associated with networking social capital, and Cambridge-Boston’s apparent demise due to the absence of such sociability. However, Saxenian did not deploy the language of ‘clusters’, that term being first used in a regional science context by Czamanski and Ablas (1979), based in turn on Czamanski’s (1974) study of industry clustering using linkage analysis. Indeed, the term evolved out of the study of industrial complexes, consisting mainly of large corporate entities and their linkage structures, inspired by Perroux (1955/1971), whose own growth pole concept derived from his application of the Schumpeterian idea of innovative ‘swarming’ on to a spatial canvas, initially the Ruhr Valley. Thus, from the Ruhr Valley to Silicon Valley, the cluster concept has been part of an ongoing effort to decipher the lineaments of an evolving economic landscape.

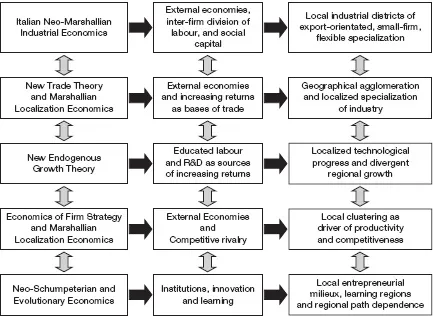

Approached more systematically, at least five such perspectives, including cluster theory itself, can be distinguished, each having different theoretical foundations and employing different terminology. But all share one thing in common: an emphasis on the role of localization as a source of increasing returns or externalities for firms (Figure 1.1). Interestingly, this focus on the externalities of localization is arguably itself part of more general ‘return to increasing returns’ in economics (Buchanan and Yoon, 1994): geography, it seems, has provided a mechanism for (re)introducing increasing returns into economic theory. The argument is that many of the increasing returns in contemporary industrial economic development are regional or local in origin, in the form of local externalities associated with industrial localization, and that, to understand such issues as trade, competitiveness, innovation, and productivity, we need to examine these local externalities. A second common thread linking these different perspectives is that, in stressing the local nature of many external economies of increasing returns, these authors also – to varying degrees – emphasize the importance of local economic specialization. In fact, what underpins much of this new focus on the external economies of industrial localization is, in effect, a resurrection of Alfred Marshall’s notion of industrial districts that he talked about a hundred years ago (Martin, 2005).

Figure 1.1 Increasing returns and economic localization: five theoretical perspectives compared

External economies of localized specialization were central to Marshall’s discussion of ‘industrial districts’ (Marshall, 1930, 1919). His characterization of these specialized industrial districts was cast in terms of a simple triad of external economies: the ready availability of skilled labour, the growth of supporting ancillary trades, and the development of a local inter-firm division of labour in different stages and branches of production, all underpinned and held together by what he referred to as the ‘local industrial atmosphere’, by which he meant shared knowledge about ‘how to do things’, common business practices, tacit knowledge, and a supportive social and institutional environment. For Marshall, these industrial districts were the logical outcome of the process of economic evolution, whereby an economy progresses by inventing yet further subdivisions of function (‘differentiation’) and more intimate connections between them (‘integration’) (Martin, 2005). He saw industrial districts as an alternative mode of industrial organization to the large integrated firm with its internal economies of scale (Marshall, 1930, p. 266):

[External economies of scale are] those dependent on the general development of the industry … which can often be secured by the concentration of many small businesses of a similar character in particular localities: or, as is commonly said, by the localization of industry.

The links back to Marshall’s work are most evident in the Italian school of industrial economics that has focused on identifying and explaining the success of the specialized, export-orientated, small-firm-based industrial districts of the so-called Third Italy (that area of the country embracing the Veneto, Emilia-Romagna, Toscana, and the Marche). Led by such pioneers as Becattini, Brusco, and Bagnasco, this school has used Marshall’s original work as a basis for a revitalized conceptualization and theorization of industrial districts (see Asheim, 2000; Paniccia, 2002). Thus we find Becattini (1990, p. 40) referring to the Italian industrial districts in very neo-Marshallian terms:

Each firm tends to specialise in just one phase, or a few phases, of the production process typical of the district. The firms of the district belong mainly to the same industrial branch … defined in … a broad sense as it includes upstream, downstream and ancillary industries.

But where Becattini and his colleagues depart most notably from Marshall’s conception is in stressing that – at least in the Italian case – the industrial district is a socio-cultural as well as economic entity: ‘a socio-economic territory which is characterised by the active presence of both a community of people and a population of firms in one naturally and historically bounded area’ (ibid., p. 39), or what Piore and Sabel (1984) called the ‘fusion’ of...