This is a test

- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Shipping and Ports in the Twenty-first Century

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Shipping and port systems are vital to societies and lifestyles around the world. In the late twentieth century, however, assumptions concerning the robustness of these systems were severely shaken by economic shocks triggered by oil crises. This volume explores how many of the consequent uncertainties have been resolved, and how adapted systems ha

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Shipping and Ports in the Twenty-first Century by David Pinder,Brian Slack in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Betriebswirtschaft & Business allgemein. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Contemporary contexts for shipping and ports

David Pinder and Brian Slack

Introduction

The twentieth century was a period of transformation for ports and shipping. At the dawn of the last century, coal-fired ships were the norm; tramp steamers scoured the world for business; European-registered vessels dominated sea-borne commerce; ships of all kinds spent much time in port; ports themselves were labour-intensive; complex and extensive port communities were consequently distinctive elements of urban docklands; and concerns over the environmental impacts of ports and shipping were virtually non-existent. As the century progressed, each of these features changed, some steadily, others rapidly. Writing in 1981, the editors of Cityport Industrialisation reviewed this dynamism through the work of a wide range of shipping and port specialists, and speculated on the issues likely to be encountered towards the end of the century (Pinder and Hoyle 1981). More than two decades later, in the early years of the twenty-first century, this present volume provides an opportunity to build on that analysis. In doing so, attention is focused on three recurrent, interrelated and key contexts highlighted by the 1981 review: globalisation, technological change and the environment.

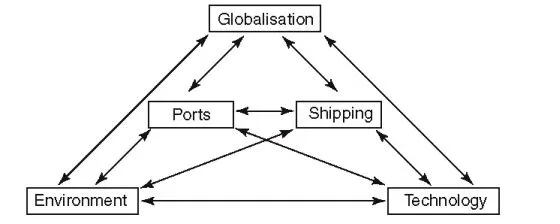

As we demonstrate, in the early 1980s the reciprocity between these contexts and the shipping and port systems was already evident. Globalisation, technology and the environment were impacting in many fundamental ways on maritime industries, and were in turn being shaped by feedback channels from the industries themselves (Figure 1.1). Yet while this was clear, the early 1980s was also a time of great uncertainty. Long-established assumptions had been shaken by economic crisis, to the extent that likely future interaction between the shipping and port systems, on the one hand, and globalisation, technology and the environment on the other, was now highly debatable. Against this background, important issues to be considered today are the questions of how this uncertainty was resolved, and how the outcomes contributed to radical developments that are currently reshaping the maritime and port industries of the new millennium.

To explore these questions, the contributions to this volume have been structured into three sections, each concerned primarily with one of the main contexts. But while globalisation, technological change and the environment make useful part titles, it is important to stress that – because of the themes’ inherent interrelationships – most chapters touch on more than one theme and would, indeed, be incomplete unless they did so. Within each chapter the authors have naturally adopted individual approaches, so that the reader is confronted with issues as diverse as corporate strategy, port governance, performance evaluation, cultural change, technological adoption and adaptation, citizen participation, and strategic response to the environmental movement. This diversity adds greatly to the relevance, interest and value of this book; without it there would in many instances be the danger of misleading oversimplification. Yet diversity also makes the case for an overarching view of the volume, a task we aim to undertake in this chapter. In doing so, we set the various contributions in a broader perspective, starting with the contextualisation of globalisation, technological change and the environment in the climate of uncertainty that was so pervasive less than a quarter of a century ago.

Figure 1.1 Globalisation, technology and the environment: interlinkages with shipping and ports.

Shipping, ports and late-twentieth-century uncertainty

Globalisation today is a very broad concept – many would say vague. A recent book provided 35 different definitions (Streeton 2001). In the economics and business literature it is recognised as promoting the financial and commercial expansion of a world economy that has become increasingly integrated (Dicken 2003). In politics, global issues are seen to shape the relationships between states (Dunn 1995). As regards the environment, many forces of change operate at the planetary scale. In culture, the influence of television, cinema and the Internet are diffused across the globe (Friedman 1995; Scott 1997). Even terrorism has gone global, thanks to al-Qaida!

In the early 1980s, however, well before the term ‘globalisation’ gained popularity with politicians and the public, its focus was clearly on global economic restructuring. Within this context, shipping and port developments were key enablers of the globalisation process. The emergence of oil supertankers had facilitated the unprecedented growth and modernisation of advanced economies from Western Europe to Japan (van den Bremen 1981; Molle and Wever 1984a, b; Odell 1986; Pinder 1992). Adaptation of supertanker principles had created dry-bulk carriers, greatly enhancing global trade in commodities such as coal, iron ore and bauxite (Takel 1981). To meet the demands of these trends, major ports had invested heavily in Maritime Industrial Development Areas (MIDAs). And ports were also investing extensively in the relatively new concept of containerisation, creating and equipping the terminals for the new generations of container ships that were already globalising trade in manufactured goods and components through dramatic efficiency gains and transport cost reductions.

Yet while the past interaction of shipping, ports and globalisation was clear, in 1981 the future seemed highly uncertain. The post-1945 growth era, remarkable for both its length and its strength, had been ended by the oil crises of 1973–4 and 1978–9 (Odell 1986). It was by no means evident that energy consumption in the advanced economies would rebound from the post-crisis slump. Large-scale investment in heavy industries had been scaled down rapidly, as plans were abandoned and many major corporations contemplated plant closures to rationalise their production systems. In these post-Fordist circumstances, what did the future hold for ports whose recent development had been dominated by the growth culture? Was it even safe to assume that the most spectacular recent advance – containerisation’s emergence and rapid take-off – would not succumb to a worldwide slump in trade caused by the economic shocks of the 1970s?

Technological change, meanwhile, lay at the heart of almost everything that had driven the unprecedented advance of shipping and port systems between the 1950s and the 1980s. Bulk carriers for oil and dry commodities would have been imposssible without major new insights into loads, stresses and their management through progress with ship design and construction techniques (Figure 1.2). They would also have been pointless without technological advances in handling that enabled bulk commodities to be loaded, unloaded, organised and stored in port areas on a much greater scale, and with far greater efficiency, than had previously been possible. Containerisation echoed and reinforced all this: new types of ship based on radically different design concepts; a revolution in the nature and capacity of the quayside crane; and equally impressive advances in other handling equipment to improve the speed, rationality – and therefore the cost – of quayside storage. But how, and on what fronts, would technological change proceed in the new and highly uncertain post- 1970s investment climate? On the one hand, weak economic conditions seemed highly likely to be coupled with the rapid advance of information technologies (IT) to achieve greater levels of computerised automation and, consequently, cost economies. This could be envisaged with respect to both the manning of ships and port-based cargo handling and industrialisation. In other respects, on the other hand, it was far from evident how the driving force of technological change would, or could, evolve. Had not the imperative for further advance of the bulk commodity trades been undermined by the economic crisis? And if recession was to be a feature of the post-Fordist era, could the economic climate sustain the continued acceleration of containerisation technologies?

Figure 1.2 The bulk coal carrier El Carribe C discharging in Le Havre. (Courtesy of the Port Autonome du Havre.)

So far as the environmental costs of shipping and port system development are concerned, it cannot be argued that in 1981 their scale and significance were fully understood. Science was far less advanced than today. Public understanding of the environmental issues was commensurately lower. The Fordist ethos, prioritising economic growth, still tended to dominate debate. Yet despite these handicaps, appreciation of the environmental costs of trade expansion, industrialisation and port growth was taking root. In particular, Fordist growth had impacted on cityport populations through negative externalities such as air pollution (Figure 1.3) and traffic congestion, while the seemingly remorseless creation of new port areas had eroded ecologically rich estuarine and coastal wetlands on an unprecedented scale (Pinder and Witherick 1990). On these foundations, movements had begun which posed the first serious challenges to the postwar ambitions of port authorities and their shipping industry clients. But, once again, these movements were surrounded by uncertainty in the early 1980s. Would they wither away as economic crisis swung the pendulum firmly in favour of economic development rather than environmental protection? Might they simply become redundant as ports, industries and the new breed of container shipping companies backed away from serious investment plans whose economic rationale had now become questionable?

Figure 1.3 Emissions to air from a Rotterdam refinery, 1978. (Photo David Pinder.)

The twenty-first century: global and local in the maritime sector

Experience over the past two decades points clearly to the conclusion that uncertainty surrounding port industrialisation and containerisation has been resolved in dramatically different ways. Although there are naturally exceptions, in general the impetus for heavy port industrialisation has never re-emerged in the post-Fordist era. On the contrary, MIDAs have slipped from the research agenda, and partial port de-industrialisation – to which we return in relation to ports and the environment – has not been unusual (Harcombe and Pinder 1996). Consequently, the imperative for change in shipping systems and ship technologies in order to facilitate the heavy industrial globalisation process has also failed to recover. Containerisation, however, contrasts sharply with this experience. Fears that recession might halt the advance of this sector proved entirely ill-founded as the global marketplace continued to develop rapidly, with the result that, as Slack details in Chapter 2, container shipping has been transformed (Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.4 Two generations of container crane: Rotterdam (1978) and Oakland (1996). (Photos David Pinder.)

Slack demonstrates how the need to serve the global marketplace has exerted enormous pressures on the shipping lines to extend their services and increase capacity. For most lines the costs of meeting these challenges have been considerable, and have dictated reorganisation of the industry. Concentration, achieved through mergers and the formation of strategic alliances, has been necessary to gain significant advances with service networks, ports of call and vessel size. These are changes with far-reaching spatial consequences, including new configurations of shipping services, the emergence of hub-and-spoke networks and, through the port selection process, resultant impacts on the growth prospects of ports. Here we see both an extension of the spatial scale of linkages and a deepening of the intensity of services, classic responses to the demands of globalisation as highlighted by Beresford1 (1997) and Giddens2 (1990). Beyond this, however, the influence of globalisation in the restructuring of container shipping should not be allowed to obscure the fact that containerisation itself is helping to shape globalisation. The multi-ocean networks of alliances that now exist, and the integration of lesser markets into mainline services, are powerful forces contributing to the expansion of the global economy. The new patterns identified by Slack form an evolving architecture helping to define the actual spatial character of contemporary globalisation.

What we also see emerging from these restructuring processes is the issue of conformity or homogenisation. As indicated earlier, the globalisation concept is now very broad, as evidenced by cultural studies in which the homogenising impact of global media, commerce and their values on human activity and experience – from food to cinema and television –- is seen as a significant threat. In the maritime context the emergence of global carriers and the formation of strategic alliances is interpreted by Slack as a signal that diversity in container shipping is being lost as a result of competitive pressure. His analysis is that container shipping companies have become more uniform as they have striven to serve the global marketplace, calling at the same hub ports, with vessels of the same type and offering similar service frequencies.

Further evidence of the extent of this homogenisation trend emerges strongly from research by Comtois and Rimmer into container shipping developments in China, the most dynamic market in the world (Chapter 3). Over the past ten years, China has become the centre of very considerable growth in container traffic, and has been drawn increasingly into the global economic system. What is notable about these shifts is not only the scale of integration into the global economy, but also how this is being played out in an economic system that is transforming itself from a command economy to one that is becoming increasingly open. Comtois and Rimmer reveal the strategies employed by the major Chinese shipping group COSCO in order to adjust to the competitive pressures of globalisation and the internal political changes in China. As a company that was originally a state-owned enterprise, COSCO has implemented a programme of modernisation that has transformed the organisation into a corporation that is commercially based and characterised by an impressive new range of horizontal and vertical linkages. The outcome is that it has become one of the major container carriers in the world, and an actor in other fields ranging from container leasing to joint ventures for container terminal development. While achieving this, COSCO has stayed apart from the main global alliances and network structures, but at the same time has relied heavily on lessons learned from their growth experiences. Consequently, the company’s development strategies have to a great extent been modelled closely on those pursued by western container corporations, with the result that the ‘new’ COSCO could increasingly be mistaken for a clone of its homogenised western counterparts.

While globalisation has frequently led to such convergence at the global scale, a great deal of social science research has concluded that global processes impact differentially at the local or regional levels. Cultural distinctiveness shapes issues or processes as varied as advertising (Hannerz 1996) and production technologies (Gertler 1997). In the environmental fie...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Figures

- Tables

- Contributors

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- 1. Contemporary Contexts for Shipping and Ports

- Part I: Global and Local In the Maritime Sector

- Part II: Technology the Enabler

- Part III: The Environment – Towards a New Harmony?