![]()

PART A

THE INNER NATURE OF LANGUAGE

![]()

1

LANGUAGE AS AVAILABLE SOUND: PHONETICS

M.K.C.MACMAHON

1.

SOUND

Sound is the perception of the movement of air particles which causes a displacement of the ear-drum. The air particles are extremely small—about 400 billion billion per cubic inch—and when set in motion create patterns of sound-waves. Certain concepts in acoustics (frequency, amplitude, waveform analysis and resonance) provide the bases for an understanding of the structure of these sound-waves. The subject is dealt with by Fry (1979).

2.

PHONETICS

Phonetics (the scientific study of speech production) embraces not only the constituents and patterns of sound-waves (ACOUSTIC PHONETICS) but also the means by which the sound-waves are generated within the human vocal tract (ARTICULATORY PHONETICS). PHYSIOLOGICAL PHONETICS, which is sometimes distinguished from articulatory phonetics, is concerned specifically with the nervous and muscular mechanisms of speech. The term GENERAL PHONETICS refers to a set of principles and techniques for the description of speech that can be applied to any language; it should be distinguished from a more restricted type of phonetics concerned with those principles and techniques which are required for a phonetic statement of a specific language. Hence, for example, the phonetics of English will require some theoretical constructs which are not necessary for the phonetics of Swahili, and vice versa. In this article, the aim is to present the essential features of a general phonetic theory.

The discipline of phonetics has a long history. In India, it originated in the work of certain Sanskritic linguistic scholars between about 800 and 150 BC (see Allen 1953:4–7 for details). In Europe, amongst the Classical Greek and Roman linguists it did not achieve the same importance, although the phonetic descriptions of Aristotle, Dionysius Thrax, and Priscian merit attention (see e.g. Allen 1981). In the Middle Ages, a number of Arab and Muslim scholars showed considerable interest in phonetics (see Bakalla 1979 for a summary). From the sixteenth century onwards, especially in Britain and Western Europe, the subject attracted the attention of a number of scholars, but for a long time, until well into the nineteenth century, much of the work was carried out under the aegis of other subjects such as rhetoric, spelling reform, and language teaching. Starting in the second half of the nineteenth century and continuing into the present, the discipline has determined its own fields and methods of enquiry, building on concepts in anatomy, physiology, acoustics and psychology, and freed itself from its association with other disciplines—although its connection with linguistics remains a close one. (The articles in Asher and Henderson 1981 trace the historical development of particular aspects of phonetics.) At the present time, much of the research in phonetics is undertaken in departments and phonetic laboratories in Britain, Europe and Japan; the contribution from North America, although important, has been relatively small in relation to the number of institutions devoted to linguistics.

3.

ORGANS OF SPEECH

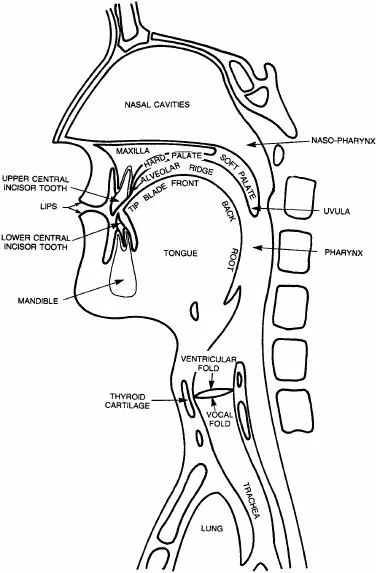

The sound-waves of speech are created in the VOCAL TRACT by action of three parts of the upper half of the body: the RESPIRATORY MECHANISM, the voice-box (technically, the LARYNX), and the area of the tract above the larynx, namely the throat, the mouth, and the nose. They constitute what are known collectively as the organs of speech. For most sounds, air is stored in and transmitted from the LUNGS (see below under Air-Stream Mechanisms for the exceptions). It is forced out of the lungs by action of the rib-cage pressing down on the lungs, and of the diaphragm, a large dome-shaped muscle, which lies beneath the lungs, pressing upwards on them. Air passes then through a series of branching tubes (the bronchioles and bronchi) into the windpipe (technically, the TRACHEA). At the top of the trachea is the larynx. The front of the larynx, the ADAM'S APPLE (the front of the THYROID CARTILAGE), is fairly prominent in many people's necks, especially men's. Anatomically, the larynx is a complicated structure, but for articulatory phonetic purposes it is sufficient to take account of only two aspects of it. One is its potential for movement, the other is that it contains two pairs of structures, the VOCAL FOLDS and VENTRICULAR FOLDS. The latter lie above the former, separated by a small cavity on either side. The vocal folds are often called the vocal cords (or even vocal chords) or vocal bands. They lie horizontally in the larynx, and their front ends are joined together at the back of the Adam's Apple but the rear ends remain separated. However, because of their attachments, they can move into various positions: inwards, outwards, forwards, backwards and, tilting slightly, upwards or downwards. They are fairly thick, and when observed from the back are seen to bulge inwards and upwards within the larynx. The ventricular folds are capable of a similar, though less extensive, range of movements.

For most phonetic purposes, it is sufficient to be able to say that the vocal folds are either (i) apart—in which case the sound is said to be VOICELESS, (ii) close together and vibrating against each other—then the sound is VOICED, or (iii) totally together—in which case no air can pass between them. Further information about the action of the vocal and ventricular folds is given below in section 10.3 under State of the Glottis and Phonation Types.

Directly behind the larynx lies a tube running down into the stomach, the oesophagus. Both the oesophagus and the larynx open into the throat, the PHARYNX. This is a muscular tube, part of which can be seen in a mirror—the ‘back of the throat’ is the back wall of the central part of the pharynx. Out of sight, unless special instrumentation is available, are the lower and upper parts of the pharynx. The lower part connects to the larynx. The upper part, the NASO-PHARYNX, connects directly with the back of the NASAL CAVITIES. These are bony chambers through which air passes. At the front of the nasal cavities is the nose itself.

The contents of the mouth are critical for speech production. Starting with the upper part of the mouth, we can note the upper lip, the upper teeth, the ALVEOLAR RIDGE (a ridge of bone at the front of the upper jaw (the MAXILLA), which forms part of the sockets into which the teeth are set), the HARD PALATE and the SOFT PALATE. The soft palate (also called the VELUM because it ‘veils’ the nose—see below) finishes in the UVULA (Latin= ‘little grape’). The soft palate, unlike the hard palate, can move, and when it is raised upwards it will make contact with the back wall of the pharynx and thereby prevent the movement of air either into the nasal cavities from the pharynx or vice versa. The movement of the soft palate can be observed by saying the vowel sound in the French word blanc and observing the back of the mouth in a mirror, and then saying the vowel sound in an English word like pa. For the French vowel, the soft palate will be lowered; for the English one, it will be raised.

The bottom part of the mouth contains the lower lip, the tongue, and the lower jaw (technically, the MANDIBLE), to which the tongue is partly attached. Although there is no obvious anatomical division of the tongue, in phonetics it is essential to have a method for referring to different parts of it. Hence it is traditionally divided into five parts: the TIP (or APEX), the BLADE, the FRONT (a better and more realistic term for this would be the middle), the BACK and the ROOT. An additional feature is the RIMS, the edges of the tongue. The boundaries between the five ‘divisions’ are established on the basis of where the tongue lies in relation to the roof of the mouth when it is at rest on the floor of the mouth. The tip lies underneath the upper central teeth, the blade under the alveolar ridge, the front underneath the hard palate, and the back underneath the soft palate. The root is the part of the tongue that faces towards the back wall of the pharynx. The reader should refer to Figures 1, which shows the outline of the organs of speech in a mid-line section of the head and neck, and should identify the position of as many as possible of the speech organs in his or her own vocal tract. A dentist will be able to show the actual shape and size of the hard palate from a plaster cast. A more detailed anatomical description of the organs of speech can be found in Hardcastle 1976.

X-ray studies of the organs of speech of different individuals show quite clearly that there can be noticeable differences—in the size of the tongue, the soft palate and the hard palate, for example—yet regardless of genetic type, all physically normal human beings have vocal tracts which are built to the same basic design. In phonetics, this assumption has to be taken as axiomatic, otherwise it would be impossible to describe different people's speech by means of the same theory. Only in the case of individuals with noticeable differences from this assumed norm (e.g. very young children or persons with structural abnormalities of the vocal tract such as a cleft of the roof of the mouth or the absence of the larynx because of surgery) is it impossible to apply articulatory phonetic theory to the description of the speech without major modifications to the theory.

4.

INSTRUMENTAL PHONETICS

Information about the postures and movements of the vocal tract in speech comes from three sources: what the speaker can report as happening, what an observer can see to be happening, and what particular forms of instrumentation can reveal. Much phonetic theory is based on the first two sources; the sub-discipline of phonetics that considers objective data derived from instrumentation is known as INSTRUMENTAL PHONETICS or EXPERIMENTAL PHONETICS. In what follows, data from the latter source will be quoted and illustrated whenever appropriate. For a résumé of the range of instrumentation available to the phonetician, see Code and Ball 1984 and Painter 1979.

Figure 1. The organs of speech.

5.

SEGMENTS AND SYLLABLES

Unless we are trained to listen to speech from a phonetic point of view, we will tend to believe that it consists of words, spoken as letters of the alphabet, and separated by pauses. This belief is deceptive. Speech consists of two simultaneous ‘layers’ of activity. One is sounds or SEGMENTS. The other is features of speech which extend usually over more than one segment: these are known variously as NON-SEGMENTAL, SUPRASEGMENTAL or PROSODIC features. For example, in the production of the word above, despite the spelling which suggests there are five sounds, there are in fact only four, comparable to the ‘a’, ‘b’, ‘o’ and ‘v’ of the spelling. But when the word is said fairly slowly, the speaker will feel that the word consists not only of four segments but also of two syllables, ‘a’ and ‘-bov’. Furthermore, the second syllable, consisting of three segments, is felt to be said more loudly or with more emphasis. (The subject of non-segmental features is dealt with below.)

The nature of the syllable has been, certainly in twentieth-century phonetics, a matter for considerable discussion and debate. Despite the fact that most native speakers of a language can recognise the syllables of their own language, there is no agreement within phonetic theory as to what constitutes the basis of a syllable. Various hypotheses have been suggested: that the syllable is either a unit which contains an auditorily prominent element, or a physiological unit based on respiratory activity, or a neurophysiological unit in the speech programming mechanism. The concept of the syllable as a phonological, as distinct from a phonetic, unit is less controversial—see, for example, O'Connor and Trim 1953; and Chapter 2, section 7.2.

6.

LINGUISTIC AND INDEXICAL INFORMATION IN SPEECH

It is necessary to draw a distinction between information in the stream of speech, both segmental and non-segmental, that is linguistic in nature and information that characterises the individual speaker. Thus, a sentence like ‘When did she say she was coming?’ must be articulated in such a way that the listener hears ‘she’, not ‘he’; similarly, ‘coming’ not ‘humming’—the pronunciation of the sentence has to be such that the...