![]()

1

Greek, All too Greek

An Invisible Gaze

Once upon a time, in the court of a rich and powerful kingdom, there lived a man who was a loyal bodyguard and close friend of the king. One day, so the story goes, the faithful servant was cordially ordered by his master to gaze at the queen while she undressed, in order to be fully convinced of her overwhelming beauty. He had to remain unseen, however; it was considered a deep disgrace in those regions for a man, let alone a woman, to be seen naked. With great reluctance the man obeyed the unusual order and watched as he was bidden, but clumsily he failed to remain unseen. The insulted queen forced him to choose between two options: to pay with his own life for his lèsemajesté; or to eliminate the treacherous husband and become the legitimate observer of the queen’s beautiful body. He quite reasonably chose the second way, and with the queen’s help he stabbed the king in his marriage-bed, in the very same place where the first offence had been committed. The lucky servant inherited the kingdom with its queen and reigned over it happily ever after. Five generations later his heir, the great emperor Croesus, was gravely punished for the ancient offence against the legitimate ruler of the land.

Herodotus relates this tale about Gyges and the king of Lydia (I.8–14, 91). Glaucon, in the second book of the Republic, tells a story about ‘one of Gyges’ ancestors’ (359e–360b).1 In Plato’s version, Gyges, or his ancestor, found a ring on a finger of a huge, naked corpse2 lying inside a hollow bronze horse that lay in a chasm created by an earthquake and a rainstorm. The ring had the power to make its wearer invisible. After Gyges accidentally discovered this power he used the ring to enter the palace where he slept with the queen, killed the king with her help, took over the kingdom and reigned happily over it ever after, a just man in the eyes of gods and men alike.

Some modern philologists have tried to determine whether Plato’s is a stylized version of the tale told by Herodotus or an independent narrative about a different figure. Aside from the name Gyges and the fact that in both cases a servant usurps a kingdom and a queen with her help, at first sight the two stories seem to have little else in common.3 Moreover, all known ancient sources who retold or referred to Plato’s version4 took Gyges to be the hero of the story and did not refer to Herodotus. Deciding the philological issue at stake, or even settling the historical question (were there one or two Gyges’) has no philosophical significance. Yet the structural similarity between the two versions may provide the key for a new understanding of the Republic in its entirety. With its help we can discern a structure that pervades and unifies the text as a whole, and endows the two main thrusts of the dialogue – the political and the philosophical – with their proper place and significance.

When Glaucon tells the story of Gyges in the Republic, the role of the myth seems obvious, i.e. to illustrate the kind of argument required from Socrates. Let us believe, the brothers – Glaucon and Adeimantus – say, that justice is good in and of itself, and that it would still be good even without the rewards given to one who appears to be just and all the evils people inflict on one who appears to be unjust. It seems that the miraculous ring is a figurative, rather primitive, illustration of the notion of the ‘in-itself’, which has later gained such an honorable place in philosophical discourse. A truly just man is one who possesses the ring and never abuses its power. The ring is a criterion for having a certain quality, justice, independently of the judgment of others. Already Cicero, who mentioned the myth of Gyges in a different context, understood it not as an imaginary situation but as a hypothetical one. According to Cicero, the story depicts a situation that is not logically impossible, and, while preserving all the elements relevant for the judgment of the just and the unjust, makes the case of justice as hard as possible (De officiis III.39). The naked body, the hollow bronze horse, the queen, all were considered, from Cicero onward, mere emblematic details, redundant from the point of view of serious philosophical discussion; the lesson of the story has become all important, the act and form of telling the story has usually been ignored.

Mythos and Logos

Odd ornaments, however, should not be ignored; the acts that display them should be examined and the logic that governs them deciphered. Approaching a Platonic text with a clear-cut separation between ornaments and serious matters, myth and argument, is highly problematic. Such an analytic approach ignores the fact that the separation itself is, in part, the task and achievement of the Platonic dialogues, and hence cannot be presupposed or projected retrospectively as a fait accompli; rather, the process of its creation should be carefully reconstructed. Moreover, assuming that Plato has already isolated and overcome patterns of mythical thinking, the analytic approach blinds one to the extent to which Plato’s discourse is still pervaded by remnants of mythical discourse and is not free of their constraints.

Indeed, when Plato wrote his first dialogues, Greek writers were already quite aware of a certain distinction between mythos and logos, which as late as the middle of the fifth century BC were still synonyms, referring to speech rather than to writing (Detienne 1986:92 ff.). There are numerous indications, in Plato and elsewhere, that story and argument are to be conceived as distinct discursive entities, though the exact relations between them is not always clear. Protagoras, for example, conversing with Socrates, supplements the story he tells about justice with a straightforward argument (Pr. 320c– 324d), but he bases his truth claim on both story and argument. The long exchange between Socrates and Protagoras about long and short speeches (Pr. 333e–339e), like other interludes in the early dialogues, is nothing but a Platonic attempt to legitimize the argument based on Socratic questioning as the sole form of ‘truthful discourse’ (alethinos logos). Separating stories from arguments, Plato was actually striving to establish the rules of a new kind of discourse, which I prefer to call – taking an appropriate distance from Plato’s own terms – ‘serious discourse,’ i.e. discourse motivated by a will to truth, dedicated to the production and examination of truth claims.

The history of the distinction is a rather long and complicated one (Detienne 1986:92ff.) and I am not going to dwell upon it here, except to mention that even in the first decades of the fourth century BC the truth value or otherwise of mythos and its precise relation to logos were not yet settled matters. A generation earlier Herodotus hardly used mythos and still used logos in the sense of an account of both credible and incredible stories, with no clear differentiations between a realistic and a legendary frame of reference. Thucydides, on the other hand, is famous for his insistence on the truth and accuracy of his accounts, which he directly opposes to the fabulous (to muthodes) characteristic of the other type of stories. These stories may be charming but are uninformative and unilluminating regarding events that really took place (Thuc. 2.22.4; Vernant 1980:190–1; Detienne 1986: ch. 3). Thucydides represents a general attitude toward myth in Plato’s time that takes it as an anecdotal story, marvelous or amusing, but at any rate incredible, without even an implicit truth claim of its own. But clearly, and despite his attack on the poets, Plato is not part of this general attitude. The truth of an incredible story may be extracted through its allegorization (Vernant 1980:197–204) and a story which seems incredible is yet to be believed, as Socrates tries to convince his interlocutors in the Gorgias and the Phaedo (Detienne 1986: ch. 5).

We have then two distinctions, both of which are familiar to Plato’s contemporaries, yet not unproblematic. Story is distinguished from argument, but the difference between the two forms in their value for serious discourse is not yet established or secured. Fabulous stories are distinguished from credible accounts, but the distinction is not based on a clear criterion, and one could always argue that a seemingly incredible story is after all true. And so, despite a growing suspicion toward myths (muthodes), they are still much in use, and in Plato perhaps more than in any other philosopher of the period. Myth continues to be that treasure of common wisdom and expression which intrigues imagination, and provides a moral lesson for the educated participants of serious discourse (Havelock 1963). Plato, moreover, seems to use it consciously in the service of serious discourse when the argument reaches its limits (for example, the three myths of judgments in the Gorgias, Phaedo and the Republic, or the myth about the principles governing the realm of becoming in the Timaeus).

But when myth is incorporated into serious discourse, and even when seemingly governed by its logic, the effects cannot be entirely controlled. Or, more precisely, to straighten the matter historically, the separation between mythos and logos was neither complete nor abrupt, and in Plato’s time patterns of mythical thinking still governed discourse, even Platonic discourse, to a certain extent at least. When examining this presence of myth, in both its more latent and more overt forms, one cannot remain within the scope of the self-understanding of contemporaries, who could never become fully aware of the way in which they themselves were still arrested by the logic of myth. If one is willing to assume that Greek mythology is not different from mythologies in other cultures, one should be ready to discuss myth in Greek discourse in the late fifth and early fourth centuries BC in terms much different from those of the Greeks themselves.5 Serious discourse robbed myth of its truth claims but not of its logic; it could employ myth only to the extent that it shared myth’s main structures; it could see through myth, a moral lesson or an argument for which the story was an example, only to the extent that it was unable to see myth for what it was.

The logic of myth, I assume, following the general structuralists’ claim, consists of certain regularities of oppositions and homologues of discursive units. These regularities pervade stories, which otherwise may differ widely in content, style, time and place. They create a structure for an indefinite number of variations that exemplify the same logic, the same relations between key categories of thought, the same way to categorize the world and to impose order on human experience, providing similar necessary differentiations for human conduct. They provided Greek discourse with a grid that served logos as a point of departure in its search for truth, a map of the terrain where it was able to move, of the questions it was allowed to ask, and of the answers it was able to provide. Even Aristotle, who more than others brought large parts of that grid to the surface of discourse hardly tried to problematize it but rather to give it its clearest formulation.

In what follows I will argue that despite the (widely studied) fact that Plato ingeniously invented new myths, inverted old ones and used both for the sake of his arguments,6 there remains in his text a layer of discourse in which the logic of myth constrains the logic of the arguments. Once that layer is uncovered and those constraints are understood, the entire text may be deconstructed and the main ways of reading it unfolded. This deconstructive reading permits a reconstruction of the Republic as a unique, more or less unified series of textual acts, a discursive deed, a special nexus in the network of relations between discourse and praxis in Greek culture at the beginning of the fourth century BC. We will also be better able to understand the historical effects of the text, which have lasted well into the modern era and made possible its role in a series of interventions in various networks of relations between philosophy and politics.

Inversion

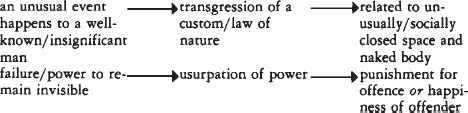

A certain similarity between Herodotus’ and Plato’s versions of the myth of Gyges has not escaped the notice of modern scholars, but neither has received special consideration. A close look at the two tales reveals a striking similarity, not in details, but at the structural level, such that it is possible to tell both at once:

The daily routine of a [well-known/insignificant] man, a servant to the king of Lydia, is broken by an unusual [order of the king/natural phenomenon]. Driven by a force he finds hard to resist, the man enters [a forbidden space in the king’s palace/ an enclosed space underground]. There he gazes at the naked body of [a woman/a dead man] whose [beauty/stature] surpasses [that of any other woman/that of a human body], and thereby transgresses [a sacred custom7/law of nature]. Soon after, the man is seen by [one who was not supposed to see him/nobody, if he wishes]. The [failure/power] to remain invisible leads the man, with the cooperation of the queen, to murder the king and take over the kingdom. [The man reigns for the rest of his life and dies peacefully; his crime is avenged five generations later. When told, the crime and its punishment are explicitly related to the Solonian conception of happiness./ Whether or not the man is happy, and whether or not he may suffer punishment for his crime are open questions to be dealt with in the rest of the text.]

More schematically the common order may be presented thus:

Figure 1.1

That Plato and his audience were familiar with Herodotus’ story of Gyges or a version of it is highly probable. That Herodotus was familiar with the version Plato used is most unlikely (otherwise, the omission of such a marvelous story is inexplicable).8 Taken against the background of what is generally accepted about the two versions, their comparison makes it all the more probable that Plato manipulated a well-known myth, and, as he often did, incorporated it into his text for his own purposes. Plato replaced the societal context of the event that precedes the major action with a natural one. He created supernatural and artificially enclosed spaces (the chasm, the bronze horse) instead of social ones (the palace, the queen’s bedroom). In the inner space he replaced the nudity of a beautiful woman with the nakedness of a huge corpse. These are the more obvious contrasts; but between the two versions there is a series of less conspicuous oppositions that have to be explicated systematically.

1) Plato problematizes the unambiguous moral lesson of Herodotus’ story; the point where the historian’s narrative ends is a renewed point of departure for the Platonic discussion of justice and happiness. Throughout the story of Gyges and his descendants Herodotus illustrates the traditional concepts of divine justice (dike¯) and happiness, concepts of which he is fond and which he attributes here to Solon.9 Justice is basically retribution for wrongdoing. The scores are balanced by the gods, not in the span of one’s life but rather in the span of one’s dynasty. Croesus is punished for Gyges’ sin five generations after it was committed (Herodotus I.91). The moral agent is not the doer of the deed, a ‘person’, but a family, a clan, sometimes a whole city. Punishment is assigned to a human group according to some divine calculation.10 On the other hand, the happiness, rewards and suffering of an individual seem to be wholly accidental, unrelated to his moral conduct, a destiny. Whether or not one is really happy – as Croesus learns, first from Solon and then from his own experience – can be determined only at death, w...