This is a test

- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Constraints and Impacts of Privatisation

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book contains papers on some 25 countries written by experts directly connected with privatisation, either as academics or as policy makers and practitioners, with a comparative review at the end by the editor. It highlights the major factors in the success and the failings of privatisation attempts in different countries in Europe, America, Latin America, Africa, Asia and Australasia. In particular there are studies on the evolving experience of transformation to free market economy in the former socialist countries of Eastern Europe.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Constraints and Impacts of Privatisation by V. V. Ramanadham in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

1: PRIVATIZATION: CONSTRAINTS AND IMPACTS

V.V.Ramanadham

This chapter addresses two questions: what are the constraints operating on privatization; and what are the impacts of privatization, either experienced or likely to materialize? Incidentally, the interrelationships between the questions are also brought out at relevant places.

One prefatory observation: the focus of this study is analytical, with empirical references occasionally brought in while building up an argument or explaining a point. The country-specific chapters will provide details of actual experiences.

THE CONSTRAINTS

Introduction

There is ample evidence to support the view that privatization has been heavily conditioned by one constraining factor or another in the cross-section of countries in the developing world and in Eastern Europe. Either it has been limited in relation to the aggregate size of the public enterprise sector, or it has been limited when compared with pronouncements of policy and conceived programmes. The following is a selection from authoritative observations in support of this conclusion.

Apart from a very few countries…such as Chile and Mexico, the vast majority have not succeeded in substantially reducing the size of the public sector.1

Taken as an indicator of the success or failure of a policy, the extent of privatisation has so far remained fairly limited both as compared with the number of public enterprises in existence and as a percentage of total public sector value added.2

A recent Oxford study of seven countries concluded that ‘progress…has been slower than hoped’. ‘Actual outcomes had been qualitatively disappointing. Privatisation to date has played only a small role in the reform of the SOE sector.’3

It is easy to identify from the growing literature on the subject a large number of countries where privatization has been constrained in some way or other: e.g. Ghana,4 Kenya,5 Poland6 and Hungary.7

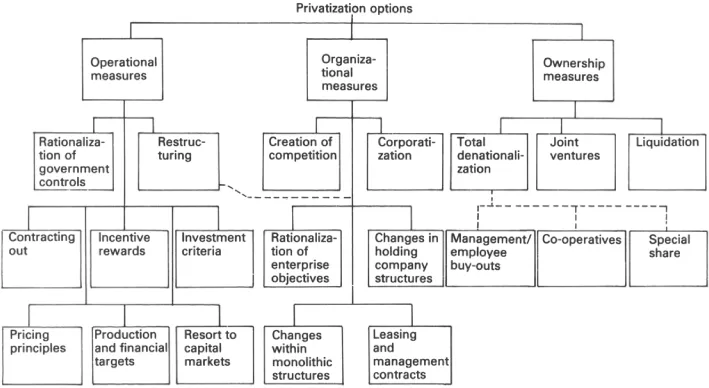

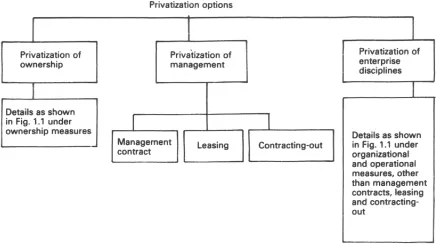

At the outset we need to annotate the term we use in this analysis, privatization. Basically, it represents marketization of enterprise operations and can be sought through three options—ownership changes, organizational changes and operational changes. These are from the structural or action angle. From the substantive or content angle, the same idea may be re-expressed in terms of privatization of ownership, privatization of management and privatization of enterprise disciplines. Figures 1.1 and 1.2 reflect the details of the options in the two cases.

Each option might be characterized by a different set of constraints (and so might its impacts be different). While there is a general tendency to treat ‘privatization’ in terms of divestiture, it is analytically useful to address the constraints on (and impacts of) the non-divestiture options distinctly. This is justified, in particular, by the very importance attached to non-divestiture options in many countries. In fact there is none which is totally free from them.

For example, Ghana has a two-phase strategy of privatization: first, rationalization and second, divestiture.8 Nigeria has a clearly announced four-pronged policy: full privatization, partial privatization, full commercialization and partial commercialization.9 The last two and the second itself in a sense can be governed by constraints belonging to the category of non-divestiture constraints. In Vietnam a significant segment of the economy is expected to stay in the public sector.10 Thailand’s public enterprises are, in substantial part, not likely to be transformed to private ownership immediately; the 1992–6 plan merely emphasizes ‘improved efficiency of state enterprises’.11 Between 100 and 150 large enterprises are nearly certain to remain in the public sector in Hungary; and new laws are enacted to deal with their stewardship. The Ethiopian proclamation on investment conceives of reserving certain areas for the government, some for its investment in partnership with private investors, and some for future policy determination, while releasing many areas for private investment.12 China, to cite one more example, has plans, gradually, of appropriate separation between ownership and management; it has applied different forms of ‘contract responsibility’ in the majority of its public enterprises; it is encouraging a variety of enterprise reorganizations, reform of enterprise employment and wage systems, and the development of new horizontal economic associations and enterprise groups, in an effort to establish a new economic system which approximates to a market economy.13

The concept ‘constraints’ has to be understood not only in terms of the pace and size of privatization but also in terms of the success of privatization. Constraints are not necessarily uniform in the two cases. Both senses apply to divestiture as well as non-divestiture options. This has not been recognized adequately yet. If one may generalize, attention to constraints has, by and large, been limited to divestiture in the former sense, so far.

Figure 1.1 Privatization options from the structural angle

Figure 1.2 Privatization options from the content angle

The idea of constraints on the success of a privatization measure or a series of privatization measures calls for annotation. It goes beyond the mere fact that, for example, an enterprise has been sold away or fully subscribed for. It touches on the accomplishment or otherwise of the basic objective of privatization, viz. efficiency gains in the composite micro-cum-macro sense. (These need some working definition, no doubt.) The more the objective is realized, the higher is the success of privatization in point of results. Where such a success factor is low, it can boomerang on the very pace and size of privatization. It would be desirable, therefore, to keep an eye on the circumstances constraining the success factor, so that remedial measures can be promptly introduced. To illustrate: where efficiency gains are constrained by the emergence of monopoly post-privatization, measures may be introduced to promote competition.

Incidentally, this line of analysis underscores the importance of identifying the impacts (actual or likely) of privatization measures. The second section of this chapter (‘The Impacts’) will go into this question.

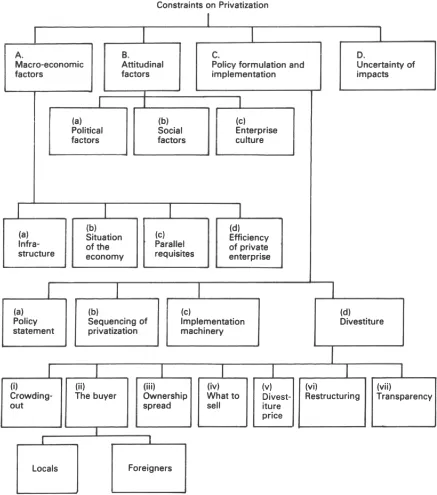

An analytical framework of constraints

Figure 1.3 is designed to present the multitude of constraints in an appropriately classified manner. Many of them apply to the entire range of privatizable enterprises, while some particularly affect specific sectors of activity and a few might be specific to given enterprises.

Figure 1.3 Framework of constraints on privatization

Macro-economic factors

These, more or less, reflect the developmental status of the economy. It is fair to say that it is in this respect that the background for privatization varies between being conducive in the developed market economies, and being restrictive—in varying degrees—in developing and centrally planned economies in transition.

Infrastructure

This is an omnibus term and ranges over several factors which individually and jointly provide the setting for the operation of enterprises, including privatized enterprises, and for the very acts of privatization. These may be considered under four headings:

- legal environment;

- capital markets;

- infrastructural services—largely in the nature of public utility facilities; and

- information facilities.

Legal environment This refers, first, to basic laws and regulations relating to the operations of enterprises, governing and—more importantly—facilitating their establishment, working and exit; laws concerning commercial behaviour, e.g. contracts, and sale of goods; and laws relating to financial institutions, e.g. banks, insurance companies and investment trusts.

Second, it refers to macro-economic laws governing matters such as foreign capital, foreign exchange, taxation, monopoly practices, prices, wages and employment. We shall look at two of these, in illustration. It is common knowledge that many countries have long been rather restrictive on the free influx of foreign capital; the laws had to be amended and/or new laws created permitting its easy inflow deemed vital for the success of privatization. Since this subject is a sensitive one, several governments have faced difficulties in promoting legislation that was sufficiently permissive and yet not provocative of discontent or sense of discrimination among local investors. The more the limits on the entry and privileges accorded to foreign capital, the heavier the constraints on divestiture in countries looking for sizeable foreign capital as a success factor in privatization. Similarly, where legislation to curb monopolies does not exist or is too weak, privatization tends to be constrained under the weight of real or perceived fear of privatized monopolies.

Third, it refers to laws specifically dealing with privatization. There can be several sub-divisions here: e.g. overall laws on privatization; laws on sectoral or specific-enterprise privatization; laws on specific techniques of privatization such as employee buy-outs or voucher distribution; laws on restitution and other issues connected with the claims of past owners; and laws governing the utilization of divestiture proceeds.

It is evident from the literature that many developing countries find themselves constrained in the design and implementation of privatization programmes because important parts of the legal instruments described above are not in place, properly or at all. Experience shows that when they began to promote the necessary legislation delays occurred, clarity was missing, inconsistencies arose, and there remained gaps in legislation. For example, the very conversion of public enterprises into independent economic units endowed with the same status as private companies was facilitated in Albania as late as early 1992, after the passage of the Law on State Enterprises in January that year.14 ‘Great inconsistencies in legislation’ are reported in Bulgaria, e.g. in small privatization. Besides there has been a lack of clarity regarding the ownership of businesses which have been on sale, absence of clarity on restitution procedures, and serious errors in the procedural guidelines for auctions. Interestingly enough, illegal privatizations and dishonest appropriations have been possible without violating the letter of the law in many cases.15 It is said that in China practice differs from the law, e.g. in the area of bankruptcy.16 In Czechoslovakia, it is reported, there is no valid law for bankruptcy.17 With reference to Russia, it is said that ‘concepts of private property and rule by law had shallow roots even in pre-communist times’.18

The issue of restitution has been one of the most knotty bottlenecks in many countries—not only in Eastern Europe but elsewhere too, e.g. in Ghana, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Uganda.19 Land title is still in the name of the original owners in the case of some ‘taken-over’ enterprises in Pakistan. The German law on restitution offers itself as an interesting illustration of the legal constraints on privatization. For instance, the sale of a ‘claimed asset’ makes the seller liable to damages; whereas in the case of the sale of an enterprise the buyer becomes liable in respect of land which is the subject of ‘claim’ by past owners. An added complication has resulted from the recent legal sanction for the transfer of a restitution claim. The transferee can prove competence as potential owner and manager of an enterprise under divestiture; and his rights have to be duly considered.20 The Czechoslovak law allows restitution claims to be settled with the new owner—a source of uncertainty for the new owner. The problem is compounded by the desire of certain claimants to buy even parts of the enterprise property which are not strictly the subject of the restitution claim.21

Legal constraints have a force vis-à-vis non-divestiture options also. The uncorporatized status of a public enterprise can itself operate as a bottleneck in bringing its operations under market disciplines. Statutes of public corporations, unlike companies which operate under the general Companies Act, often contain provisions necessitating certain governmental controls inconsistent with marketized operations. (For instance, such enterprises cannot acquire loans for their business operations without obtaining ‘special permission from various organisations’ in Ghana.)22 Statutes that place control in the hands of the workers—e.g. through workers councils—might prove inconsistent with market-oriented decision making. Such legal constraints not only condition the success of a non-divestiture option adopted but limit the interest of the government to adopt it as an effective option and of the management to act on it as a genuine option.

Capital markets The underdeveloped nature of the capital markets operates as a serious constraint on privatization in many ways.

First, divestitures are hard to implement since the local investment potential is too inadequate. There arises a disproportionate interest in wooing foreign capital. (For instance, about 90 per cent of the divestiture incomes in Hungary are reported to have come from abroad, by January 1992.)23

The issue of inadequate cash resource potential on the part of the buyers of privatized enterprises warrants deeper analysis. Assuming that there is enough effective demand for a few initial divestitures, the divestiture proceeds can be recycled into the private sector if the government chooses to pay back public debt in corresponding amounts. And this process can be repeated and divestitures for cash consideration can continue to take place. There are, however, several qualifications:

- The government bond holders who receive cash might not be the ones who are interested in equity subscription.

- A part of the cash receipts on bond redemptions might find itself diverted to consumption.

- The government might decide to use the divestiture incomes in other ways than repaying public debt, on consideration of budget balance. This breaks the chain of recycling.

Second, underdeveloped capital markets give a distinctive twist to the techniques of divestiture. They might prompt private sales—through negotiation—as in Ghana up to 1991. (The problems and criticism associated with such sales dampen the government’s pace of divestitures.) Divestitures might be undertaken on credit terms, in part, such that the buyers of shares could complete the payment for shares over a period. Or, the government may be induced to divest on the basis of a free distribution of shares (or vouchers), so that ownership privatization occurs without cash figuring as purchase consideration.

Third, capital markets which are unconducive to fast divestitures might interest the government in adopting non-divestiture options, at least as an immediate measure. A major part of East Africa illustrates this.

It is true that sporadic improvizations for the sale of shares can be contemplated, circumventing the disadvantage of unpropitious capital markets. For example, post offices and bank offices can be involved in functioning as places where intending applicants for shares may go, fill in the forms and deposit the application moneys. Jamaica adopted this metho...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- FIGURES

- TABLES

- CONTRIBUTORS

- PREFACE

- 1: PRIVATIZATION: CONSTRAINTS AND IMPACTS

- 2: PRIVATIZATION IN THE UK

- 3: PRIVATIZATION IN EAST GERMANY

- 4: PRIVATIZATION IN HUNGARY

- 5: PRIVATIZATION IN POLAND

- 6: PRIVATIZATION IN CZECHOSLOVAKIA

- 7: PRIVATIZATION IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE

- 8: PRIVATIZATION IN GUYANA

- 9: PRIVATIZATION IN ARGENTINA

- 10: PRIVATIZATION IN BRAZIL

- 11: PRIVATIZATION IN MOROCCO

- 12: PRIVATIZATION IN TANZANIA

- 13: PRIVATIZATION IN ISRAEL

- 14: PRIVATIZATION IN BANGLADESH

- 15: PRIVATIZATION IN INDIA

- 16: PUBLIC ENTERPRISE POLICY AND THE MOUs

- 17: PRIVATIZATION OF STATE-OWNED ENTERPRISES: A FRAMEWORK FOR IMPACT ANALYSIS

- 18: ACCOUNTING ASPECTS OF PRIVATIZATION IMPACTS

- 19: CONCLUDING REVIEW