eBook - ePub

Strabo of Amasia

A Greek Man of Letters in Augustan Rome

Daniela Dueck

This is a test

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Strabo of Amasia

A Greek Man of Letters in Augustan Rome

Daniela Dueck

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Strabo of Amasia offers an intellectual biography of Strabo, a Greek man of letters, set against the political and cultural background of Augustan Rome. It offers the first full-scale interpretation of the man and his life in English. It emphasises the place and importance of Strabo's Geography and of geography itself within these intellectual circles. It argues for a deeper understanding of the fusion of Greek and Roman elements in the culture of the Roman Empire. Though he wrote in Greek, Strabo must be regarded as an 'Augustan' writer like Virgil or Livy.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Strabo of Amasia by Daniela Dueck in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Historia antigua. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

STRABO’S BACKGROUND AND ANTECEDENTS

AMASIA

Strabo of Amasia is known particularly for his geographical survey of the world of his time, the first century. But the work is more than the outcome of research and compilation of sources undertaken by a Greek scholar. It also supplies personal information about Strabo, being the only ancient source to throw light on his personality, which, as far as can be assessed, to some extent explains the nature of his writings. In this sense the man and his book are inseparable and present a mutual reflection, each of the other.

Strabo’s intention was to survey the entire inhabited world. Dealing with northern Asia Minor, and describing the region of Pontus, he depicts Amasia, and mentions by the way that he was born in this city (12.3.15, C 547; 12.3.39, C 561), situated in central Pontus, about 75 km distant from the southern coast of the Black Sea.1 This reticence is typical of all the biographical allusions and remarks scattered in the Geography, which are never part of a systematic self-presentation of the author, but appear somewhat sporadically throughout the work, to compose only an incomplete image. Thus, even Strabo’s birth-date is no more than a conjecture and derives from what he chose to reveal in his work as we have it.

The Suda notes that Strabo ‘lived at the time of Tiberius’2 but this notion is too general and seems to refer to his prime as an active scholar. A better assessment of the birth-date was suggested by Niese who surveyed all the temporal phrases in the Geography such as ‘a little before my time’ (mikron pro hemon) and ‘in my time’ (kath’ hemas or eph’ hemon), interpreting them as literally referring to Strabo’s lifetime since Strabo always refers to himself in the plural, the ‘authorial we’. By collating these general temporal references with accurate dates derived from other sources, Niese tried to establish the period to which Strabo applies the term ‘in my time’. Referring to the political situation in Paphlagonia Strabo says that ‘this country…was governed by several rulers a little before my time, but…it is now in possession of the Romans’ (12.3.41, C 562). It was Pompey who organized the region after subduing the Asian Iberians and the Albanians and before his campaign in Syria and Judaea, that is, in the first half of 64 BCE. Since according to Strabo’s phraseology these events occurred shortly before his time, meaning, as Niese understood it, shortly before he was born, Niese thought it possible to conclude that Strabo was born later that same year. This date is further made plausible by Strabo’s comments on events occurring in the following year, which he already defines as happening in his lifetime, for instance, Galatia being governed by three rulers (12.5.1, C 567), a system ascribed to Pompey on his return from Syria at the end of 63 or the beginning of 62 BCE. It is true that Strabo applies the expression ‘in my time’ to his entire lifetime and to incidents covering a wide range of dates; still, Niese thought that the earliest events defined by these temporal expressions fix the year of birth in 64 BCE.3

In a recent article Sarah Pothecary has challenged Niese’s conclusions, suggesting that these temporal clauses should not be taken as literally referring to Strabo’s actual birth-date, for in order to thus understand them one would have to assume that every reader was indeed familiar with this exact date, otherwise the notion would not make any sense and would not serve any dating purpose. She therefore concludes that these clauses mean ‘in our times’ and differentiate between two historical periods, an earlier one when Pontus was an independent kingdom and a later one when the kingdom came under Roman domination, following Mithridates VI Eupator’s defeat by the Romans and the reorganization of the region by Pompey roughly after 66–63 BCE. Hence, Strabo’s exact date of birth cannot be discerned, though it is possible to put it between the years 64–50 BCE.4 Pothecary’s suggestion complies quite well with the chronological range deriving from the temporal clauses in Strabo, and although she challenges Niese’s understanding of these clauses, the end result concerning the birth-date is still that it was probably not before 64 BCE.

The date of Strabo’s death is also closely connected to his Geography and may be estimated in relation to the assumed date of composition of the work (chapter 6, p. 146), and the latest year alluded to in it. Strabo mentions the death of King Juba II of Mauretania and Libya, and the ascendance of his son Ptolemy to the throne (17.3.7, C 828), occurring in 23 CE.5 Since this is the most recent event mentioned in the Geography, it indicates that Strabo was still alive at the time, and therefore that his death took place sometime after this year.

Suggestions as to the place where Strabo died also vary. This has again to do with the assumed place for the composition of the Geography, in Strabo’s later years (below, p. 14), assuming that the place where he wrote the latest parts of the work is the place where he died shortly after he finished writing. Accordingly, the sites suggested are Amasia and Rome.6 Strabo’s notion of Naples is of interest in the present context:

greater vogue is given to the Greek mode of life at Naples by the people who withdraw thither from Rome for the sake of rest, meaning those who have made their livelihood by training the young, or still others who, because of old age or infirmity, long to live in relaxation.

(5.4.7, C 246)

This was taken by Honigmann as a hint at Strabo’s own withdrawal in his last years from Rome to Naples where he may have died.7 But as we shall see, Strabo’s acquaintance with Rome after Augustus’ death, and the probability that he composed the Geography in Rome at a later date, suggest that he also died there.

Amasia, and Pontus as a whole, require further attention, for the region underwent some political and geographical transformations which affected Strabo’s family and possibly his approach to the politics of his adult life.8 Prior to the Hellenistic era Pontus was one of the Asian satrapies of the Persian empire. The independent Pontic dynasty originated in the highest circles of the ruling Persian nobility in Cius. Mithridates III of Cius fled to Paphlagonia after his father was killed by Antigonus and after he defeated certain Seleucid forces. In 281 BCE he became the first king of the Pontic dynasty and thus acquired the name Ktistes, ‘Founder’. His descendants continued the dynastic line until the reign of Mithridates VI Eupator.

The kings of the Pontic dynasty, each in turn, tried to extend the borders of the kingdom as well as to establish political relationships with neighbouring kingdoms through intermarriage. They tended to emphasize their local Iranian-Anatolian origins and at the same time in their courts and in their foreign relations they adopted the Hellenistic monarchical style. Thus Greek became the official language of Pontus. While a full account of the activities and policies of the Pontic kings down to the approximate time of Strabo’s birth is out of order in this context, it will be useful to refer briefly to the ambitions of Mithridates VI Eupator who finally confronted Rome on Asian soil. Like his predecessors, Eupator extended the kingdom and in fact made it into the largest in existence. He also had some Roman contacts, such as Sertorius in Spain, and even bases in Greek territories in Athens and Boeotia. When the Romans finally decided to deal with his growing power, they challenged him in Greece and in Asia to a series of battles, during three ‘Mithridatic’ wars. Beginning in 97 BCE, these fierce struggles finally came to an end in 66 BCE with Eupator’s refusal to surrender the kingdom to the Romans, and his death, perhaps by suicide. Pontus became part of the Roman province of Bithynia and Pontus. Under Antony some of the cities were ruled by native rulers, but in Augustus’ time the west part of Pontus again became a Roman province, while the eastern part was governed by the dynasty of Polemon and Pythodoris.

The Roman domination of the Pontic region changed the political map not only by dividing it into parts of dissimilar political status, but also by joining areas of the Pontic kingdom of Mithridates to the adjacent Bithynia. Thus Pompey subjected the regions around Colchis to local rulers and divided the rest into eleven political units comprising part of a new and larger province, Bithynia-Pontus.

Several times in his Pontic survey Strabo shows the complexity of the political situation in those years. The Roman governors following Pompey created new divisions, in some cases appointing rulers and kings, in others granting autonomy, even freedom, and in others keeping the cities under direct Roman control (12.3.1, C 541). The changes of rule in various cities also reflect the general fate of Pontus. For instance, Sinope was first subdued by Pharnaces, then by his successors in the Pontic dynasty down to Eupator, then by Lucullus, and ‘now’ has a colony of Romans who own part of the city (12.3.11, C 545–6). Again, Amisus, first possessed by the Pontic kings, was besieged by Lucullus, then by Pharnaces from the Bosporus, freed under Julius Caesar, handed over to local kings by Antony, later ruled by the tyrant Straton, and finally made independent by Augustus (12.3.14, C 547).

Due to these constant political permutations, the geographical borders of Pontus kept shifting. Pontus lies on the southern coast of the Black Sea, surrounded by Armenia Minor in the east, Bithynia in the west and Cappadocia in the south. The region is topographically divided into two large sections, the coastline and the mountainous inland region. Most of its cities were originally early Greek settlements founded along the seacoast, such as Sinope, Amisus and Pharnacia, whose economy and character were determined by maritime commerce. Amasia was the largest inland urban centre. Most of the other settlements in the interior were villages, generally more affected by earlier Iranian—Anatolian culture.

The Pontic kings in general and Eupator in particular admired and fostered Hellenistic civilization. Eupator’s court seems to have been full of Greek scholars, some of whom, such as Apellicon of Teos, also occupied political positions.9 As we shall see, Strabo’s family was among those who surrounded the kings, becoming part of an elite Hellenistic aristocracy.

The description in the Geography and some archaeological findings show that Amasia was a typical Hellenistic city in its monuments and culture (12.3.39, C 561). There were several temples, the main one devoted to Zeus Stratios, others to other divinities, some of them eastern, such as the Great Mother, Mithras and Serapis. The city possessed a theatre, a stadium and an aquaduct. The whole complex was surrounded by a wall, parts of which can still be seen on the ledge beside the mountain. Some Greek inscriptions from Amasia and the environs predating Augustus also indicate the Hellenization of the region.10

Strabo’s interest in the affairs of Pontus and particularly his affiliation with its royal dynasty is apparent through his extensive survey of the military and political actions of Mithridates Eupator (for instance 12.3.2, C 541; 12.3.28; C 555; 12.3.40, C 562). He refers to his source for inside information as Neoptolemus, Mithridates’ general (7.3.18, C 307), thus implying access to official documents or personal contact with a key personality in the Pontic court.

The constant border movements are reflected in the name of the region, called also ‘Cappadocia near the Pontus’ (12.1.4, C 534) or ‘Cappadocia on the Euxine’.11 This explains the various geographical apellations bestowed on Strabo, Josephus calling him ‘Strabo the Cappadocian’ (ho Kappadox) and the Suda ‘Strabo the Amasian’ (Amaseus).12 Since these names are not contradictory it seems best to use the more specific rather than the more general one.

STRABO’S ANTECEDENTS

The political transformations in Pontus under Roman rule affected the behaviour and position of Strabo’s family, which held a high position at the courts of Mithridates V Euergetes and VI Eupator. Three digressions in the Geography reveal some details about the author’s ancestors.

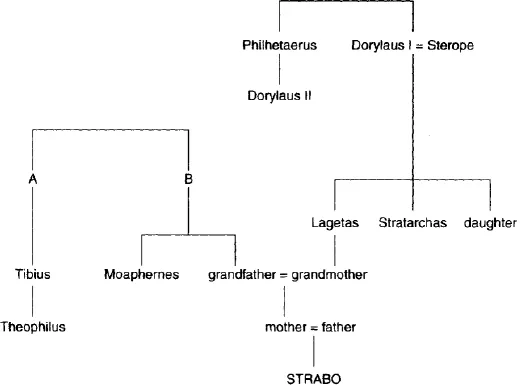

Dorylaus of Amisus, Strabo’s great-great-grandfather on his mother’s side, was closely connected to Mithridates V Euergetes. In 121 BCE the king sent Dorylaus to recruit mercenaries from Greece, Thrace and Crete. During one of his sojourns in Crete Dorylaus became involved in a local feud between the people of Cnossos and the Gortynians, and helped to end the conflict. By the time he was ready to go back to Pontus he had heard of the king’s assassination, the kingdom now being ruled by the queen and her young children. He therefore decided to remain in Cnossos where he established his own family by marrying a Macedonian woman named Sterope and begetting two sons—Lagetas and Stratarchas—and one daughter (10.4.10, C 477).

Meanwhile in Pontus, Mithridates VI Eupator, the eleven-year-old son of the murdered king, ascended to the throne. Dorylaus’ nephew and homonym, Dorylaus son of Philetaerus, was adopted as the king’s brother, and when both the king and his adopted brother grew up, Mithridates honoured Dorylaus by appointing him priest of Comana, second in rank to the king, and initiated the return of his kinsmen from Cnossos. Thus Lagetas, the son of Dorylaus the general, came to Pontus and established his family there. His daughter became the mother of Strabo’s mother, making Lagetas Strabo’s great-grandfather (figure 1). Strabo comments that as long as Dorylaus the priest prospered, his family enjoyed respect and prosperity, but when he was caught in an attempt to surrender the kingdom to the Romans, thinking that he might eventually become its ruler, the family lost its wealth and honour (10.4.10, C 477–8; 12.3.33, C 557).13

The family had another channel of relationship to the kings of Pontus, through Strabo’s maternal grandfather. Mithridates Eupator was in the habit of appointing one of his friends to the governorship of Colchis. Among them was Moaphernes, the uncle of Strabo’s mother on her father’s side (11.2.18, C 499). But Moaphernes’ brother, Strabo’s grandfather, realizing that the king could not succeed in his war against the Romans led by Lucullus, and troubled by the fate of his cousin Tibius and Tibius’ son Theophilus, both executed by the king, caused fifteen fortresses to surrender to Lucullus. But the favours and honours promised him by the Romans were not granted and were not confirmed by the Senate, for the rivalry between Lucullus and Pompey caused the latter to consider all those who helped Lucullus as enemies (12.3.33, C 557–8).

Figure 1 Strabo’s genealogy

These two stories are very similar. The two Dorylai as well as Moaphernes and his brother were of high rank in the kingdom and the closest intimates of the kings, but they betrayed Eupator by tending towards the Romans, thus humiliating and degrading their families. Strabo apparently decided to expose these intimate matters, perhaps to show his family’s high rank and at the same time, in view of his personal connections with Rome (chapter 3), and the Roman-dominated political situation of his time (chapter 4), to accentuate its willingness to cooperate with the Romans.

The family information refers exclusively to the mother’s side. Strabo’s silence regarding his father’s kin seems to imply the absence of any members worthy of mention, or perhaps a less elevated genealogy.14

Strabo’s ancestors are known through sources other than the Geography thoug...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- 1 Strabo’s background and antecedents

- 2 Strabo and the Greek tradition

- 3 Strabo and the world of Augustan Rome

- 4 Geography, politics and empire

- 5 Greek scholars in Augustan Rome

- 6 The Geography—a ‘colossal work’

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index of geographical names

- Index of personal names