This is a test

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The Roads of Roman Italy offers a complete re-evaluation of both the evidence and the interpretation of Roman land transport. The book utilises archaeological, epigraphic and literary evidence for Roman communications, drawing on recent approaches to the human landscape developed by geographers. Among the topics considered are:

* the relationship between the road and the human landscape

* the administration and maintenance of the road system

* the role of roads as imperial monuments

* the economics of road construction and urban development.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Roads of Roman Italy by Ray Laurence in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

1

INTRODUCTION

Why write a book on Roman roads? This question has occurred frequently during the research and writing of this book. Put simply, it is a topic that has been totally misunderstood by recent scholarship on the subject and has caused us to have a skewed view of the past in Roman Italy. Historians have recognised that the Roman state was involved in the development of an extensive transport network of roads from the fourth century BC, but have not managed to understand the impact of road building. Moses Finley (1973: 126–7), in the most influential study of the ancient economy for more than a generation of scholars, saw the purpose of these roads to have been political and militaristic and even later as having no significant economic impact. The reason for this explanation is given in terms of the cost of transport by land in comparison with the far cheaper forms of transport by river or sea (Finley 1973: 126–7; also De Neeve 1984: 8–17, 1985; compare Braudel 1981: 419–21). This view of the economy was followed by a generation of scholars (Duncan-Jones 1974: 1; Hopkins 1978: 3; Garnsey and Saller 1987: 44, 90) and has recently been re-asserted in Morley’s (1996) study of Rome’s hinterland. In fact, it has become a theme of economic history simply to ignore the subject, since trade by sea is seen to have been cheaper. As a result, in recent works on Roman Italy (e.g. new editions of the authoritative Cambridge Ancient History) land transport hardly receives a mention. Thus, an immediate aim at the start of the project was to address this lacuna in Roman history.

Although the book marks a counterpoint in many ways to some of the fundamental assumptions made by Finley and his Cambridge colleagues, it is written within that historical tradition. This mode of study places an emphasis on the structure of not just the economy, but other aspects of society in relation to the cultural impact of Rome. The influence of the historiographical tradition of Keith Hopkins’s Conquerors and Slaves (1978) can be found in many sections of the book. His work produced a model of change for Italy in the second and first centuries BC and of the impact of imperialism on Roman society that still remains influential and at the forefront of historical thought on ancient Italy. In this book, in contrast, I am concerned with the impact on Italy of change in the nature of transportation. In a way the book follows on from my work on Pompeii (Laurence 1994a), which was concerned with a single city study of the use of space in its temporal setting (i.e. Pompeii’s space-time), in line with an earlier study by Jongman (1988) of the economy of Pompeii in the Finley/Hopkins tradition. There I was asserting the importance of space and time for our understanding of the city in Italy, as much as its economic formation. What I wanted to do in that book was to make an initial step by subjecting Pompeii to the full force of current geographical theory and scholarly thought on space-time (see Soja 1996 for the most recent summary). I viewed the city as a unit in a wider social system in the tradition of other studies and had a preoccupation with the nature of the city stemming from Finley’s publications (see papers in Rich and Wallace-Hadrill 1991; Cornell and Lomas 1995; Parkins 1997; also Finley 1973 and 1977). The tradition of the city as an object of analysis stems from the Greek view of the city state. Although in Roman Italy the city state continued to be the basis of local government, in no way did these cities act in the manner of the Greek city states of the fifth century BC, and there is a case to be made for a political cohesion in the Italian peninsula from the first century BC (see Millar 1998: 13–48; Mouritsen 1998: 49; also Wiseman 1971: 28). The way that I view Italy in this book is as a series of cities that constitute a whole through their interconnection by the road system itself, and the action of travel and transportation. In other words the road system is seen as an example of a structure that is between places, which joins them together to create an artificial unity. This view is in tune with modern perspectives from geography that have even intruded into the study of Roman political history (Millar 1998: 3). This viewpoint avoids the pitfalls of regional studies based on abstract areas defined by ancient geographers after the events under study. The betweenness of space sums up the fluidity of the regions of the Italian peninsula under Rome and the temporal distances between places that separated them from each other. The latter would vary according to the position of a place within the network of roads at a specific time. Hence the book is about the relationship of transport to the city within the context of the formation of a unified Italy.

The intersection of the city, the traveller and the road form the basis of my understanding of how Roman Italy was constituted to create unity. The Roads of Roman Italy is an exploration of the complexed interaction of three elements: roads, cities and Italy. In doing so I set out to alter our perspectives of each element. Hence, some topics that may be seen by other authors as crucial to the study of each element may not appear here. For example, my discussion does not include the challenges of Italian citizenship in its discussion of Italy, nor every single feature of road technology or the imperial post – elements seen as crucial to earlier discussions of the politics of Italy or the description of archaeological evidence. These and others, I find less important than the changes that occurred in Italy’s space-economy that made possible the meaning of citizenship to so many and ultimately was the basis for a unified Italy. I make no apologies for doing so, because those who have discussed citizenship etc. have seldom accounted for the change in the mentalité of space-time or the betweenness of place. My object in short is to offer a view of Italy that alters our current perception and will I hope change the minds of the readers in how they see the past itself. For me, that Roman past needs to include an understanding of the spatiality of Italy in relation to the city, regions, the economy and identity in particular.

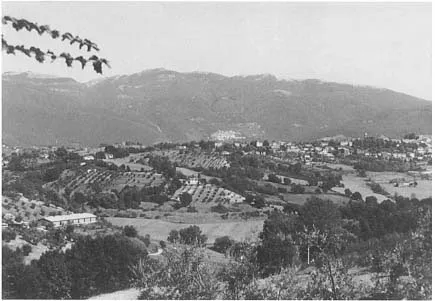

Figure 1.1 Roads follow low ridges of hills; mountain ranges limit the possibilities of transport

In writing the book, I do not reject the traditional importance of historical change. This is my major preoccupation in the first chapters of the book. Here, I set out the development of land transportation, first in the context of Roman hegemony and, specifically, the relationship between the development of Roman imperialism and road building: the cultural change from a society that was based on the city state to a state that was not a ‘nation’, but was associated with a dispersed citizenship (compare Hobsbawm 1990; Gellner 1983; Hobsbawm and Ranger 1983). These changes caused or maybe were caused by an alteration in the mentalité of space-time. This highlights a new system of thought with regard not only to the polity, but primarily to territory and space. The Roman expansion in terms of territory and change in mentalité that was associated with it provided an impetus not just for the founding of Roman and Latin colonies but also for the creation of new towns – fora. These, I argue, were foundations that were later to change their name and appear simply as municipia. The setting up of these towns was an integral part of the change in the nature of Roman space-time and they became centres for the enforcement of the state’s will. The economic viability of these places is discussed in relation to their role in the landscape of Italy. These smaller scale settlements shaped the pattern of urban settlement in Italy as much as the existing Italian towns or the Roman and Latin colonies. Underlying the new politico-spatial formation was the road system that in itself altered the geographical organisation of Italy. The development of this new spatial form is followed in Chapters 4 and 5, where I set out to analyse the politics of road development and the associated changes in road technology that reduced the temporal distances between cities. These changes in technology resulted in a shrinkage of space-time distanciation and a new view of the betweenness of space. The new mentalité is set out in Chapter 6, where I document the Roman view of Italy that was dominated by a need to travel from place to place. The analysis here includes a detailed study of the Antonine Itineraries and suggests that the itinerary as a view of space is as useful as a modern map. Hence, what I present is a vision of the growth of a space for imperialism and empire that was dependent on the use of an improved technology of transport, and a new culture of both space and distance.

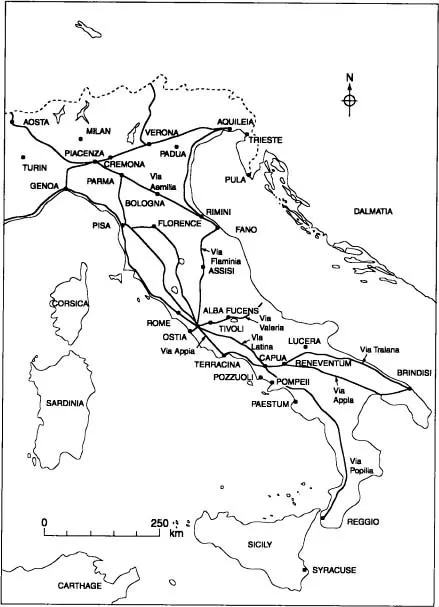

Figure 1.2 The major roads of Italy

The major question of the cost of land transport is addressed in Chapter 7. A complete overhaul of the doctrinal view of the expense of land transport is undertaken and presents a case for the study of the Roman economy within the context of practice and profit, rather than theoretical cost. In doing so, I point to the need to see road transport alongside river and maritime trade as a complementary system. The theme of river transport is followed up in Chapter 8 with a detailed study of the use of rivers and canals in Italy based on recent Italian scholarship with its emphasis on topography. Here, I have an interest to demonstrate that rivers and canals were utilised, but their use depended on human technology to control the flow of rivers and canals. The technological sophistication required for structures such as canals actually favoured road transportation. What we need to understand is the nature of transport technology and its use in practice, rather than making abstract statements with regard to the cost of land:river transport. A key problem for understanding the use of the road system is that it is difficult to place a scale on the need for transport. Predictive models of city regions drawn from the geography of modernism have failed to establish any meaning successfully to the network of roads and cities except maybe in Campania (Morley 1997; Frayn 1993: 74–100; for critique see Cosgrove 1984: 30; Laurence 1997a; Whittaker 1998).

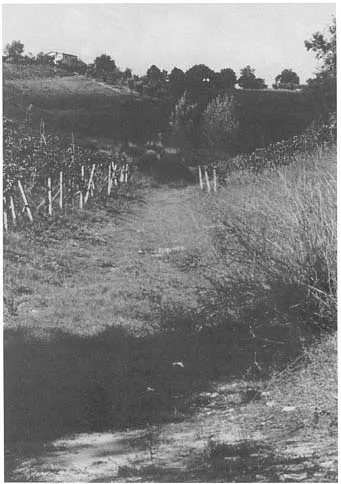

Figure 1.3 Remains of a Roman road in the Ager Sabinus

I approach the subject tangentially in Chapter 9 with discussion of the supply of improved breeds for the haulage of carts and carriages. This analysis demonstrates that the supply of mules (an improved breed) was a constant in the economy and shows a desire for a more efficient transport technology. This factor in itself points to a developing system that was reducing the temporal distances between places through measures that improved the overall efficiency of the system – through the paving of roads and the breeding of stronger animals with greater stamina than either the ass, the horse or the ox. Chapter 10 is a discussion of mobility within Italy with particular attention to the need or requirement to travel on state business. Included alongside the discussion of travel is an approach to the movement and circulation of money over distance.

The question of mobility raises another: the role and the social standing of the traveller. These questions are answered with reference to the mode of travel and the appearance of the traveller to others within Italy. What I wish to show here is that the mobility of certain sectors of the population caused major changes in the economy and the culture of travel. The interaction of the traveller with the more sedentary population of Italy is the topic of discussion in Chapter 11. Here I demonstrate that the development of public architecture in Italy was designed to be displayed to the travelling elite from Rome and elsewhere as much as to the local inhabitants. This points to the importance of a city being between places from and to which travellers make their way. The view of euergetism adopted here points to the integration of the culture of cities through the traveller’s gaze and expectation, rather than an abstract notion of ‘Romanisation’ that is seen from a perspective that stresses the city and its local population as the unit of historical analysis (on Romanisation see Laurence forthcoming). To a certain extent, travel in a way created a unity for Italy in terms of both geography and culture.

Tota Italia is the theme Chapter 12. What I wish to show is that the divisions of Italy through the use of ethnonyms was in a way a response to the idea of a unified peninsula. The use of ethnicity here is emblemic to cause a difference in our minds as readers of ancient geography, as well as in the minds of the travellers coming across towns and people. The role of roads and cities in the geographical description of tota Italia stresses again the intersection of these three units of human action that depended on the agency of travel or geographical description to invest them with meaning. The geographical unity created by a road system was undercut by a series of divisions by city and by ethnicity, which at the same time could be viewed as a single unit – tota Italia. Following on from this is a discussion of the utilisation of the Augustan regions to extend the power of the state. Geography and the control of space is a theme of Chapter 13. My intention here is to explain the reasoning behind the division of Italy into eleven regions by Augustus. The argument naturally rests on the road system and travel, in this case the protection of the traveller from banditry. This system of geography created a structure for the extension of state power not just through the individual cities of Italy, but to the roads themselves and the cities that were never far from the major roads. State power is at its most prominent when dealing with outsiders (bandits), but presumably extended to other fields of human activity as well.

My final chapter draws together what has gone before and outlines the implications of the previous chapters for our understanding of the nature of Roman Italy. This chapter is discursive and brings together the earlier arguments; its aim in short is to say what is the historical significance of a culture based on land transportation and a geography based on a road system. To enable a degree of clarity, this chapter is not heavily referenced and for further discussion the reader should refer back to the earlier chapters for detail. In no way should the statements in this chapter be seen as simple assertions since they based on what has gone before. This methodology is necessary to promote a clarity, to avoid obfuscation and to provide an opportunity to state the significance within the broader subject area of Roman history.

The chapter opens with a discussion of the state. The production of a space of transportation by land is seen as part of Roman power and created a new space of interconnection over a long distance, whereas Etruscan roads had been very localised affairs. This new form of interconnection of necessity altered the nature of the economy and requires us to adjust any economic model, in particular those of Moses Finley and Keith Hopkins. The adjustment causes the model of the consumer city to appear to over-emphasise the economic strength of the ancient city. I argue here that urban development was dependent on the circulation of the elite, as opposed to the consumption of surplus production by an elite in towns. Discussion then moves on to the role of the road in the structuring not only of geography but also of Roman power and cultural identity. In short, I argue here that the road was at the very heart of the Roman spatial system of cities, villas and agriculture.

In writing the book, I have tried as far as possible to avoid in-depth theoretical discussion that might obscure my historical argument. A discourse on space and time is not to every ancient historian’s taste, but for those who wish to know more, I refer them to two key texts that lie behind my work and summarise recent discussion in geography: E.W. Soja (1996) Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and Other Real-and-Imagined Places and D. Harvey (1989) The Condition of Postmodernity. Both Soja and Harvey provide key insights into the spatial thought of Henri Lefebvre, whose work I have discussed elsewhere (Laurence 1997b), and they provide a clear beginning or starting poin...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Mastering space: road building 312–44 BC

- 3 Town foundation in Roman Italy 300–30 BC

- 4 The politics of road building

- 5 Technological change

- 6 Time and distance

- 7 Transport economics

- 8 Inland waterways

- 9 Mules and muleteers: the scale of the transport economy

- 10 A mobile culture?

- 11 Viewing towns – generating space

- 12 Tota Italia: naming Italy

- 13 The extension of state power

- 14 Space-time in Roman Italy

- Bibliography

- Index