This is a test

- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The Copts - the indigenous Christians of Egypt - declared their independence from Byzantine Christianity when they appointed their own patriarchs in the sixth century. Jill Kamil has written an angaging and accessible survey of the history of Christianity on Egypt, through its development under Rome, Byzantium and Islam, to modern times.Drawing on

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Christianity in the Land of the Pharaohs by Jill Kamil in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Historia antigua. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

WORSHIP OF THE HOLY VIRGIN AND THE HOLY FAMILY IN EGYPT

Nearly three and a half million pilgrims a year converge on the village of Durunka, 10 kilometres south-west of the city of Asyut, half of that number during the annual mulid in honour of the Holy Virgin. Through- out the Delta and Upper Egypt pilgrims travel long distances to attend such festivals. Those that make for Durunka travel to Asyut by train, road or river and from there by taxi, donkey cart or on footpaths worn by custom beside a canal, past random shacks and occasional trees. Some pitch tents around the church dedicated to the Archangel Michael (el-Malak), others make their way towards buildings constructed to accommodate them on the lower slope of the cliff where the Monastery of the Holy Virgin is located. They bring with them all they need for their comfort: bedding, portable stoves, baskets of food, clothing. For fifteen days, between 7 and 22 August each year, the area is totally transformed. Cafés, sweet and book stalls with holy pamphlets and Christian jewellery are set up around the camp area. Fruit and vegetable vendors choose the more mobile operation of donkey carts to peddle their wares. In the corner of the marketplace, a giant wheel is set up as the focal point of a fun fair where children clad in gaily coloured clothes, the girls with bright head- scarves, delight in all the activity. This is a joyous occasion and the highlight of the celebration is a grand procession, the doura , on the last day of the festival. Long before dawn pilgrims start a three-hour walk towards the foot of the mountain where Mary, Joseph and the Christ child are believed to have taken refuge in a rock-hewn cave.

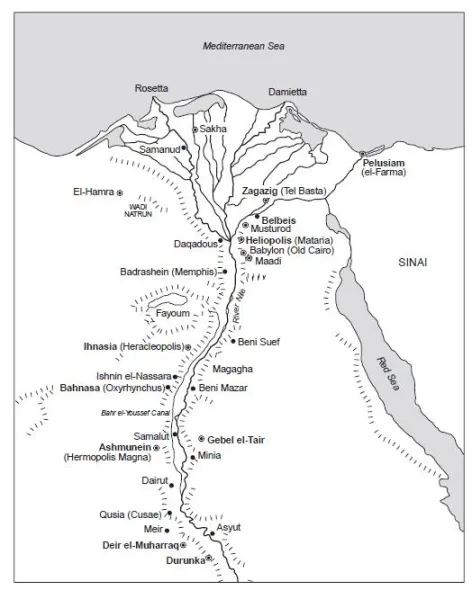

Figure 1.1 Map of sites visited by the Holy Family in Egypt

The pilgrims chant hymns as they walk towards the cliff as dawn approaches, clapping and drumming to keep beat. Meanwhile Bishop Mikhail of Asyut emerges from the cave complex built on the slope which rises 100 metres above the flood plain. He carries a processional cross and is accompanied by black-gowned priests followed by deacons in white gowns bearing a huge icon of the Virgin and Child. The clergy, in turn, are followed by dozens of other white-clad deacons also bearing crosses walking in four straight lines, heads bare and with broad, red sashes strung over their shoulders and across their chests. As they come into sight, the approaching pilgrims let out a mighty roar; children dart between the legs of adults for a better view; women ululate. As the crowd presses forward my eye comes to rest on the figure of Am Mesiha, an aged water carrier, his body bent almost double with the weight of the bloated animal carcass slung across his shoulder. At eighty, he is the oldest water carrier in Egypt, the living embodiment of a bygone age who, it is said, spends his life moving from mulid to mulid to provide water to the congregations, free of charge or for a small token of their gratitude. The bishop stops and raises the cross. The pilgrims fall silent. He blesses them with consecrated water cast from an urn held by a deacon at his side and the multitude raise their palms to intercept a drop. Incense fills the air. Hymns are sung. As a grand finale, four white pigeons are released to fly over the assemblage. ‘They symbolise the Virgin Mary’, a pilgrim whispers by way of explanation as I watch them soar above our heads.

The sight of the icon of the Virgin and Child borne by white-robed priests and doves being set to flight to carry the joyous tidings to the four corners of the earth is reminiscent of ancient Egyptian festivals depicted in numerous temple reliefs which continued well into the Christian era. For centuries, pagan and Christian existed side by side, and even after Emperor Theodosius took measures to terminate all forms of Pharaonic (pagan) worship and ritual in the fourth century, only in the reign of Justinian (527–65) was the Graeco-Roman temple of the goddess Isis on Philae, south of Aswan, officially closed. By that time Egypt’s most beloved goddess was closely associated with the Holy Virgin.

The myth of Osiris, Isis and Horus is one of the most poignant and probably the most well-known of ancient Egypt. Surviving in oral tradition and variably recounted over the centuries, it has come down to us in many versions and with many contradictions. It is appropriate to describe it as reflected in Christianity for several reasons. First, because the institution of family ideals found its earliest expression in the Pharoahse myth. Second, because it provides evidence of the early worship of relics. And finally because the tales of Isis’ devotion to her son

Figure 1.2 One of the earliest examples of Mother and Child, showing the king at the breast of an unknown goddess, is in a relief in the mortuary temple of King Unas at Saqqara (c. 2345 BC). The theme became dominant in the New Kingdom, and this relief of Isis suckling Horus in the ‘birth house’ of the temple of Horus at Edfu (237–57 BC) suggests that it provided inspiration for later images of the Holy Virgin and Child. Photo Michael Stock.

Figure 1.3 Stone plaque of the Holy Virgin with the Christ Child on her lap in high relief, which reflects a folk simplicity typical of Coptic sculpture. The Virgin raises an arm from the elbow in a gesture of piety. Christianity could not have held its own against the popular worship of Isis in her various forms had not an older cult of the virginal mother goddess been adopted. (Coptic Museum.) Photo Robert Scott.

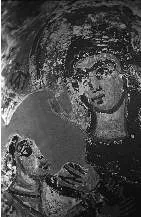

Figure 1.4 This well-preserved and delicately painted niche showing the Virgin directing her breast towards the infant Jesus, her head turned slightly towards him, is one of many from the fifthcentury Monastery of Saint Jeremias at Saqqara. (Now in the Coptic Museum.) Photo Robert Scott.

Horus whom she brought up secretly in the marshes of the Delta parallel Mary’s protection of the Christ child in Egypt.

The earliest Egyptian sources of the Osiris myth are the Pyramid Texts (2345–2181 BC ), where the story is not in connected form. The most complete version is given by Plutarch, the Greek writer ( c. 46– c. 126 AD ), according to whom Osiris, with his devoted wife Isis at his side, was a just god who ruled wisely and well. His brother Set, however, was jealous of his popularity and secretly sought to do away with him. At a rural festival Set enticed his visitors to try out a marvellously fashioned chest for size. When it came to Osiris’ turn, he unsuspectingly obliged, unaware that it had been made to his exact measurements. As soon as he lay down in it Set and his accomplices fell on the chest, shut the lid, and cast it into the Nile to be carried away by the flood. Isis was overwhelmed with grief at the news. She cast sand in her hair, rent her robes in sorrow, and set out in search of the chest. When she finally found it, she hid it beneath a tamarisk tree. Unfortunately, Set was out hunting and came upon the hiding place. He extracted the body, which he brutally tore into pieces, scattering them far and wide. The tormented Isis, this time in the company of her sister, the goddess Nephthys, set out once more on a journey to collect the pieces of the body of her husband. Having done so, she and Nephthys called on the gods to help them bind the parts together and restore the body to life. Isis crooned incantations until breath came to the nostrils of Osiris, sight to his eyes. Then, in the form of a kite, Isis descended on Osiris’ phallus and received his seed as depicted in the temple of Isis on Philae. When she gave birth to her son, Horus, she nursed him in solitude, raised him to manhood to avenge his father’s death, and consequently take over his throne. His risen father, Osiris, ruled as judge in the court of justice, gateway to the afterlife.

Egyptian texts are full of references to the love and devotion of the goddess Isis as wife of Osiris and the mother of her son Horus, born posthumously. The myth was rewoven time and again in many oral renditions and dramatised in public performances. By the Middle Kingdom (2040–1781 BC ) the cult of Osiris had thoroughly captured the popular imagination. Provincial priests who wished to give impor- tance to their temples each claimed that a part of the body, dismembered by Set, was buried in their province. In one variation of the myth the head was buried at Abydos (Abdu). In another version it was the whole body that had been found there, with the exception of the phallus that had been eaten by an Oxyrhynchus fish. Abydos was by that time fully established as a city of prime importance and a place of pilgrimage. Each year settlers would come from far and wide to witness the ritualistic killing of Osiris by his brother Set, followed by several days of mourning. The worshippers would show appropriate sorrow for the murdered god and weep and lament in the manner of Isis. Funerary wreaths and flowers would be placed on the mummified effigy that was borne through the city. The cortège would be led by Wepwawat, the jackal-god, ‘He who opens the way’. The people would sing hymns and make offerings, and at a prescribed site a mock battle would take place between Horus and Set. The murder of Osiris was avenged, and the triumphant procession returned to the temple. The crowning scene, as depicted in the temple of Seti I at Abydos, was the erection of the backbone of Osiris, the djed or pillar-like fetish.

Isis did not play a major role in the dramatisation of the myth. However, in the New Kingdom (1567–1080 BC ), when Egypt controlled a vast empire which comprised almost all of western Asia including Palestine, Syria, Phoenicia, the western part of the Euphrates, Nubia, Sudan and Libya, the goddess attained a more prominent position. In fact, in view of the role of the virginal mother in many cultures, it is worth noting that the worship of single female deities is a phenomenon that, in Egypt, can be traced to the first millennia BC. Excavations in the Mut temple complex at Karnak in the 1970s, for example, revealed that Mut’s role of consort of Amun (chief god of the Theban triad) and mother of their son Khonsu gradually expanded until she became goddess in her own right. The same can be said for Isis; when assimilated with Hathor, the cow goddess of love and nourishment, and with Nut the goddess of the heavens, she became extremely popular with the masses. The worship of Isis at Philae, too, can be dated to a period earlier than the main temple built in her honour in the reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus (285–246 BC), when it was decorated with reliefs (in the so-called Osiris Chamber) that graphically reveal the sequence of the mythological events related by Plutarch. Blocks of inscribed stone that date to the reign of the 25th dynasty Pharaoh Taharqa (690–664 BC) have been found at the site. Her cult spread beyond the southern border of Egypt, into Nubia. Later, in Graeco-Roman times, it extended to Rome; and later still even as far as the banks of the Rhine. In Egypt, fantastic tales of her magical powers were told. It was believed that Isis’ knowledge of secret formulae brought life back to her husband Osiris; that her spells saved her son Horus from the bite of a poisonous snake; that a single tear shed for Osiris initiated the annual Nile flood, the ‘new water’ used for libations in temples; and that she protected all who sought her. As the cult became diffused, Isis was known as the ‘goddess of a thousand names’. She was associated with the Greek goddess Demeter, and as Isis-Fortuna she was the Egyptian goddess who conquered the Roman world. As early as the first century AD , tokens with Isiac symbols were issued by priests in Rome, and her cult reached its peak under the emperors Severus and Caracalla.

Statues of Isis offering her breast to Horus who is seated on her lap are known as early as the Middle Kingdom and are typical of the Late Period (664–332 BC ). A 22 cm high gilded statue of the seated goddess and child found at Abu Sir (now in Cairo Museum) dates to the latter. It shows the naked boy-god Horus wearing a cap with the uraeus (cobra) symbol of kingship on his head, suckling from Isis’ left breast, which is held towards him with her right hand. Similar statues have been found in their hundreds in Egypt, and, indeed, throughout the Hellenic world. French Egyptologist Gaston Maspero was the first scholar to relate such representations to the concept of Pharaoh as son and successor of the gods, who, from the moment he became a god (on his accession to the throne), was recognised by the goddess as her son; and she consecrated his adoption by nourishing him as she would her own child. Such images prepared the way for those of the suckling Virgin Mary.

When paganism was outlawed and temples closed in the reign of Theodosius in 379 (Chapter 6) Egyptians saw, in Mary and her divine son, their own beloved Isis and her son Horus. There is little doubt that the Holy Virgin holds as prominent a place in the Coptic Church of today, as did the goddess Isis in the temple at Philae. Each was a mother figure who protected her son from those who wished him ill. The priests who annually bear the icon of the Virgin and Christ child from the cave-church in Durunka today, preceded by a priest swinging an incense burner on a chain, are performing an ancient ritual. Just as Pharaonic priests shuffled their way out of the sacred sanctuary of the temple of Isis on Philae during the spring and autumn festivals in her honour, so does Bishop Mikhail and his white-robed deacons at Durunka bear the icon of the Holy Virgin to carry in procession before adoring pilgrims. Theotokos , (Mother of God), occupies a special place in the hearts of Copts. Since pagan worship was only outlawed in the fourth century, perhaps the switch in devotion from Isis to Mary was never consciously made, at least not on the popular level.

There is a strong tradition in Egypt that supports the New Testament story of the Flight into Egypt: ‘Take the young child and his mother and flee into Egypt’ (Matt. 2: 13, 15); ‘Out of Egypt have I called my son’ (Isiah 19: 1); and it is shared by Christians and Muslims alike. There are countless sites in Egypt associated with ...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of figures

- Preface

- Acknowlegments

- Introduction

- 1 Worship of the Holy Virgin and the Holy Family in Egypt

- 2 Desert Fathers ancient and modern

- 3 Faith and oppression under Roman rule

- 4 Knowledge versus faith

- 5 Martyrs and Pachomian monasticism

- 6 The war against paganism and Christian reflection of its art

- 7 Conversion, controversy and national identity

- 8 Coptic Christianity develops its own style

- 9 Change and continuity under Islam

- 10 Restoration and revival

- Epilogue

- Appendix: notes on saints and martyrs

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index