eBook - ePub

Song from the Land of Fire

Azerbaijanian Mugam in the Soviet and Post-Soviet Periods

This is a test

- 290 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Song from the Land of Fire

Azerbaijanian Mugam in the Soviet and Post-Soviet Periods

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Song from the Land of Fire explores Azerbaijanian musical culture, a subject previously unexamined by American and European scholars. This book contains notations of mugham performance--a fusion of traditional poetry and musical improvisation--and analysis of hybrid genres, such as mugham-operas and symphonic mugham by native composers. Intimately

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Song from the Land of Fire by Inna Naroditskaya in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Russian Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

SONG FROM THE LAND OF FIRE

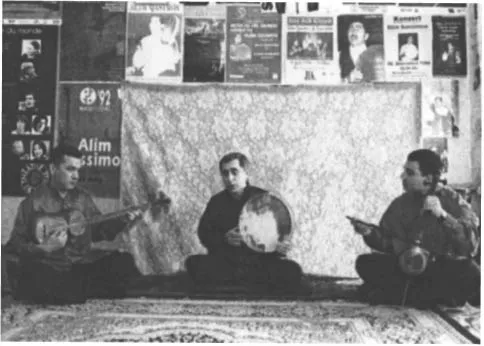

Figure 1.1. Mugham trio: tar player, khanande with gaval, kamancha player (Photograph given by Alim Gasimov's family, 1999).

CHAPTER 1

Split Identity: The Historical and Literary Heritage of Azerbaijan

A MAN SITTING IN THE CENTER OF A COLORFUL CARPET SINGS IN A HIGH-pitched nasal voice. Instrumentalists on either side accompany him, one playing a bowed spike fiddle called the kamancha and the other a lute-like tar held near the performer's chest. The intense voice of the singer spins the words into intricate melodic ornamentation that intoxicates the listener. The melody of the tar winds around the voice of the soloist, echoing, repeating, or anticipating the singer's line. The kamancha and the tar interlace like the double zigzag on the borders of the carpet.

The voice of the soloist dives into low-pitched soft speech, a love whisper. Gradually his voice rises to a dramatic recitation followed by a melodic arabesque, in which every tone becomes a center of syllabic melisma. A breathtaking ascent is interrupted when the soloist strikes the tambourine-like gaval (daf), signaling the beginning of a fiery dance-like interlude. (Sound track three: Alim Gasimov's trio)

This trio is performing mugham. To unaccustomed ears it may sound like Persian, Arabic, or Turkish music. But one who knows it unmistakably recognizes the classical music of Azerbaijan, music that brings to listeners the sweet and dense aroma of early spring in the Azerbaijanian capital Baku, the rolling undertones of the Caspian Sea, the whistle of a salty wind and the image of the Caucasus mountains covered with fiery poppies.

The word mugham has several meanings. Mugham is a modal system serving as the foundation for diverse types of Azerbaijanian music including folk and art traditions, composed pieces and pop music. It is an anthology of melodies, themes, motifs, and rhythmic gestures. Simultaneously mugham is a musical genre that weds orally transmitted music with classical written poetry. A mugham composition is a succession of improvised recitations interspersed with songs and dance-like episodes. In addition, mugham is a performing tradition identified with specific settings and purposes. The art of mugham involves particular social relationships—master and disciple, soloist and instrumentalist. The complexity of the mugham concept is inseparable from the history of the people to whom it belongs.

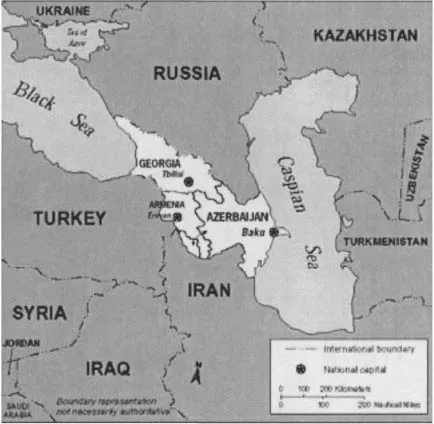

THE AZERBAIJANIAN PEOPLE

Azerbaijan, with a population of eight million people, is territorially the largest country of Transcaucasia. It is situated on the west shore of the Caspian Sea, meets the Persian plateau on the south, extends to the Armenian highlands on the west and is bordered by the Caucasus Mountains on the north. For a hundred seventy-five years, Azerbaijan was a province of the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union, but for most of its history Azerbaijanian culture, religion, and aesthetics were associated with the Eastern hemisphere. During Azerbaijan's long history, its people were at different times part of the ancient Greek, Roman, and Persian empires; lived under Arabs and Mongols; and were tossed between Ottoman Turkish and Persian dynasties.

For over a millennium, Azerbaijanians have belonged to a Turkic-speaking1 group which includes Turks, Turkmens, Tajiks, and Uzbeks. Although the spoken languages and alphabets vary, the peoples of this vast region share a significant body of narrative. Literary sources reveal the cultural closeness of Azerbaijan to neighboring Turkey. Hence even though the two countries share Islamic beliefs, Turkey is associated with Sunni Islam and Azerbaijan with the opposite camp of Shiite Islam. Azerbaijanian conformity to Shiism reflects its kinship with another strong neighbor—Iran.

The territorial, cultural, and religious ties of Azerbaijan with Iran and Turkey resulted not from trade and cultural exchange but from centuries of wars in which Azerbaijan was the arena of a power struggle between its neighbors. Located between two seas (Caspian and Black), it lies in a fruitful land with rivers that provide natural irrigation, a place with high mountains, wide valleys, and vineyards, the crossroads between Western Europe on one side and West Asia and Central Asia on the other. The territory of contemporary Azerbaijan was a “permanent theater of political affairs” and a land attracting immigrants. It had been referred to as ‘the gates of the Caucasus, the Caspian Sea, and ancient Albania’“ (Sumbazade, 1990: 16).

Archeological work in this area suggests that it was inhabited as early as four thousand B.C.E. The existence of ancient civilizations such as Mannea (in southern Azerbaijan) is discussed in Assyrian sources of the ninth-through-seventh centuries B.C.E. (Sumbatzade, 1990: 27). In the fifth century B.C.E., Herodotus described a “Caspian tribe’“ related to the modern name of the Caspian Sea. Ilias Babaev connects the Caspians with ancient Albania. He quotes Sarbon, an author of antiquity, who stated that “in the country Albania there is Caspiana, which is also a sea named by the people who had been called Caspian and who had been exterminated” (I. Babaev, 1990, 38).

Figure 1.2. Map of Azerbaijan and surrounding countries.

Around 550 B.C.E., the empire of Akhamenids, “the world's largest dominion,” took over both Media and Albania.2 In 328 B.C.E., the Akhamenids were conquered by Alexander the Great. The Median satrap Atropat, who fought against Macedonians on the side of King Darius III after the defeat of his ruler, swore allegiance to Alexander. Consequently, Atropat or Azarbad(Geibullaev, 1991, 340–341; Hunter, 1994: 7) retained the leadership of northern Media (Mannea), a province called Atropaten after the name of its ruler. Some linguists and historians believe that “the word Azerbaijan was formed from Atropaten” [Azarbad] (Alstadt, 1992: 2), while others suggest that it was derived from the name of an azeri tribe, or from the Persian word azeri, meaning ‘fire’—hence Azerbaijan, ‘Land of Fire.’ In ancient Zoroastrian temples, fires were fed by plentiful natural sources of oil (Swietochowski, 1985: 1). Although historians disagree about the precise borders of ancient Albania3 and Atropaten, it is widely accepted that both are precursors of modern-day Azerbaijan.

Major cities of antiquity existent today include Shemakha and Mingechaur, described by Ptolomy and Sarbon (I. Babaev, 1990: 2). Ganja, Sheki, Barda, Baku, and Nakhichevan were built at the beginning of the Common Era (Altstadt, 1992: 2). The people of early Azerbaijan were a conglomerate of various ethnic groups, far from homogenous in language and traditions. The first Turkic tribes appeared from the north around 93 C.E. (Sumbatzade, 1990: 76–91). D. E. Eremeev, in The Ethnogenesis of Turks, suggests that by the third or fourth century, these Turkic tribes, attracted by pastures for animals, had become permanent settlers in the Caucasus. The mixing and merging of Turkic tribes from the north with the native population was constant throughout the first millennium. Turkic migration became a decisive factor in the ethnicity of the forebears of contemporary Azerbaijanians (Sumbatzade, 1990: 85).

In 647 C.E., the twenty-fifth year of the Islamic calendar, Arabs defeated the Sassanid empire4 and entered Atropaten. Through the end of the tenth century, Arabs migrated to this territory, establishing large Arabic settlements in Azerbaijanian cities and rural areas. According to Sumbatzade, even today people living in some villages of Shusha are called Arabs (Sumbatzade, 1990: 93). Islam became the most effective force unifying the people of the region; Arabic sciences, poetry, and arts stimulated and influenced cultural changes in occupied areas. The fall of the Arabic dynasty of Abbasids resulted in the formation of a number of Azerbaijanian khanates (small kingdoms) following Arabic and Persian models.

The end of the eleventh century was marked by a new stream of Turkic tribes such as the Seljuks and Oghuzs from the southeast, Central Asia, and Iran. Gatran Tabrizi, a famous poet of the eleventh century from the Azerbaijanian city Tabriz, wrote:

These Turks arriving from Turkistan

Accepted you as their ruler

Separated from their relatives and relations

Began living under your rule

Now they are everywhere… (Dadashzade, 1994: 63).

Mobile and growing in number, Turks obtained leading positions in existing khanates or formed new ones. Between the thirteenth and sixteenth centuries, Azerbaijan became the center of countless battles among Turks, Persians, Mongols (Genghis-Khan), and local tribes. Territorial control constantly shifted among Azerbaijanians, Georgians, and Armenians. A mass influx of Turcomans resulted in a rivalry between the two states of Qara Quyunly and Aq Quyunly (Black and White Sheep) (Sumbatzade, 1990: 179). A number of small and large khanates arose in the fifteenth century among which “a native Azeri state of Shirvanshahs flourished north of the Araxes” (Swietowchowski, 1995: 2). The rulers of these powerful states endeavored to unify Azerbaijan.

By the beginning of the seventeenth century, a large centralized empire uniting thirty-two local tribes arose under the rule of Ismail Safavi, who came from a family of sheikhs in the ancient Azerbaijanian city Ardebil. The first shahinshah or tsar of tsars of Iran, he was supported by the Azerbaijanians. A brilliant commander, strategist, and poet, Shah Ismail later made the Shiite branch of Islam the official religion of his empire, an act that set Azeris firmly apart from the Ottoman Turks).

One of Ismail's adherents, Shah Abbas, revenging the murder of his mother (arranged by the Azerbaijanian nobility) beheaded many Azerbaijanian political leaders, moved the capital to Isfahan, and changed his empire from an Azerbaijanian to a clearly Iranian state. The relocation of the Safavid capital and the reformation of Azerbaijanian territory into four provinces under bäylärbäy or governors led to separation from Iran. The fall of the Safavids resulted again in the division of Azerbaijanian territory into a number of khanates, miniature political replicas of the Iranian state complicated by tribal hierarchies5 and individuals striving for power.

Russian expansionist politics towards Transcaucasia began with tsar Peter the Great (1683–1725) and his “abortive Persian Expedition of 1722” (Swietochowski, 1995: 3). Struggling for political control of the Transcaucasus, Russia, Iran, and Turkey chose Azerbaijan as the first target. In 1822, Iran conceded territory in northern Azerbaijan to Russia in exchange for help against the Afghans. In 1824, Russia and Turkey signed an agreement that ceded additional Azerbaijanian land to Russia. Russia ignored its pact with Iran and allowed Turkey to occupy Western Iran. The Turkmanchai Settlement6 finalized the division of Azerbaijan and determined its destiny for almost two centuries.

The area populated by Azeris was divided into equal parts, but a larger proportion of the Azeri-speaking population remained in Iran. Unlike the Georgians, the Azeris did not have the benefits of territorial-ethnic unity, a fact that would be seen as an impediment to their evolution into a nation. … One day, the treaty would turn into a symbol of national bitterness, a black day of historical injustice in the eyes of the twentieth century Azerbaijanian national movement. (Swietochowski, 1995: 7)

A century of Russian rule resulted in demographic changes, the development of the oil industry, the rise of urban Azerbaijan, and the formation of a native intelligentsia and a labor class. Armenian and Russian migration coincided with expanded investment in this region. The subtropical climate, undeveloped cities, and industrial potential lured people from different countries and ethnic backgrounds. Altstadt describes Baku of the beginning of the twentieth century as “a city of immigrants: less than half of the population had been born in the city, men greatly outnumbered women, and sixty two percent were under age twenty.”7

At the threshold of the twentieth century, Baku, which throughout the previous hundred years had been a “desert city [with] not yet a single street that might be considered European” (Bay, 1932: 11), was turning into a multiethnic capital with diverse languages and religious traditions, theaters, a multilingual press, and frequent performances by internationally known artists. While a majority of native Azerbaijanians were politically and culturally disadvantaged in their own land, Azerbaijan was economically and culturally favorable to everyone else, especially Russians and Armenians. At the same time, Baku was attractive for educated and talented Azerbaijanians who were deeply acquainted with their own culture, knew also Arabic, Persian, Turkish, and often Russian languages and literature. The tension between the foreigners who largely defined the features of the city and the practically alien natives associated with rural areas or the urban periphery led to the rise of nationalistic consciousness among the native intelligentsia. Their growing awareness and activity resulted in the Azerbaijanian Enlightenment. The latter was represented by intellectuals such as the writers Mirza Fatali Akhundzade (Akhundov, 1812–1878) and Hasan Melikov-Zarbadi (1837–1907), the poet Mirza Alekper Sabir (1862–1911), and the composers Uzeyir, Zulfugar, and Jeyhun Hajibeyov and Muslim Magomayev (Zenkovsky 1960: 92–107). Altstadt states that “the political and cultural Azerbaijani elite saw themselves as leaders of a community beyond Baku, encompassing [the cities of] Shemakha, Cuba, Shusha, Nakhichevan, Ganja, and countless villages” (Altstadt, 1992: 49).

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Baku became one of the industrial centers of the Russian Empire. The leaders of the democratic movement had much more freedom there than in other industrial centers, due to the city's remoteness from imperial power. In the summer of 1902, the print shop “Nina,” famous in the history of the Soviet revolution, was opened in Baku, publishing Lenin's paper Iskra. The first publication of Marx's Manifesto in Russian was also issued in Baku. In the early twentieth century, the Azerbaijanian revolutionary movement was driven by a desire to form an independent Azerbaijanian state.

The revolution was followed by a short-lived Transcaucasian Federation. After its collapse, Azerbaijan declared in May 28, 1918, the first Eastern Islamic state with a Parliament and a Cabinet of Ministers. The Azerbaijanian Democratic Republic lasted twenty-three months, attacked by Turkey, Iran, Britain, and Russia, and threatened by neighboring Armenia and Georgia. Azerbaijanian freedom ended when “with the conquest of Armenia on December 2, 1920, and Georgia on March 18, 1921, the Communist...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- CURRENT RESEARCH IN ETHNOMUSICOLOGY

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- LIST OF FIGURES

- LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES

- SELECTIONS ON COMPACT DISC

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- PREFACE

- CHAPTER 1 Split Identity: The Historical and Literary Heritage of Azerbaijan

- CHAPTER 2 “Mugham is Not Music”: The Complex Aesthetics of Islam

- CHAPTER 3 “A Wave of Melodious Sound”: The Basics of Mugham

- CHAPTER 4 The Sound of Traditional Mugham

- CHAPTER 5 The Modernization/Westernization of Mugham

- CHAPTER 6 Mugham Lineages: Fathers and Sons, Masters and Disciples

- CHAPTER 7 Symphonic Mugham

- CHAPTER 8 Women’S Voices Defying and Defining The Culture

- CHAPTER 9 Conclusion: Mugham As Signifier

- CHAPTER 10 Travel Notes: 1997 and 2002

- GLOSSARY

- NOTES

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- INDEX