- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The focus group is widely used to as a tool for increasing the understanding of users and their requirements, and identifying potential solutions for these requirements. Its main value lies in the conveyance of less tangible information that cannot be obtained using more traditional methods. Eliciting user needs beyond the functional is crucial for

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

Joe Langford and Deana McDonagh

1.1

ABOUT THIS BOOK

The fields of human factors/ergonomics and design have a common aim—to develop products and systems that successfully meet the needs of their users. A key part of achieving this aim is gaining a good understanding of the users and the ways in which they use products or systems. This includes identifying the features they value or enjoy as well as those they dislike, or which cause them problems.

There are many ways in which this knowledge can be elicited. These include user trials, questionnaire surveys and observation of people doing things in real-life situations. More recently though, there has been a growing trend to use focus group methodologies to support these more conventional methods. This is largely because the interactive and synergetic nature of group discussions (one of the central themes of focus group research) allows deeper insights into how and why people think and behave the way they do.

Focus groups are not new. Market researchers and social scientists have used them for many years and the basic principles are well defined. Designers and ergonomists have different requirements though. Whilst embracing the basic focus group concepts, they have developed techniques to help them make better use of the method to meet their specific needs.

Over the years many research papers have been published giving examples of the uses and adaptations of focus groups in human factors/ergonomics and design projects. To date though, there has not been a book which summarises this knowledge, or which provides a simple guide for ergonomists and designers who may be new to this type of research method. This book aims to fill this gap by:

- explaining what focus groups are, including the benefits and limitations;

- providing a simple how to guide to get the reader up and running quickly and easily;

- providing real-life examples of how other designers and ergonomists have used focus groups and related techniques in their work;

- providing a toolkit which summarises methods and techniques that can be used as part of focus group sessions.

Both human factors/ergonomics and design are wide in scope, encompassing many diverse activities. This book is aimed particularly at those involved in the following areas:

- Industrial design

- New product development

- Product and equipment design

- Information design

- User requirements analysis

- Human computer interaction

- Usability

- Work and workplace design

- Accidents, health and safety at work• Vehicle and transport design

- Task and systems analysis

- Training design

1.2

THE STRUCTURE OF THE BOOK

After this introduction, there are three main sections to the book:

Part I. Organising and conducting a focus group: the logistics. This is a simple how to guide for ergonomists and designers who are new to focus groups. It provides practical advice on the key aspects of planning, recruiting participants, setting up the facilities, running sessions and analysing the results.

Part II. Focus groups in human factors/ergonomics and design: case studies. This section provides examples of how focus groups and related techniques have been used in human factors/ergonomics and design projects. The chapters are written by practitioners and researchers from Europe and North America and cover a wide range of different applications, illustrating the flexibility of the method. Where appropriate, guidelines for using focus groups in specific scenarios are given.

Part III. Focus group tools. Techniques that can be used as part of focus groups are summarised here, including creativity and thinking tools. This can be used for quick reference when planning sessions.

1.3

WHAT IS A FOCUS GROUP?

In broad terms, a focus group is a carefully planned discussion, designed to obtain the perceptions of the group members on a defined area of interest. Typically there are between five and twelve participants, the discussion being guided and facilitated by a moderator. The group members are selected on the basis of their individual characteristics as related to the topic of the session. The group-based nature of the discussions enables the participants to build on the responses and ideas of others, thus increasing the richness of the information gained.

Focus groups can be used as a self-contained research method or as part of a collection of research methods, quantitative or qualitative. Usually, they are conducted in a series, with at least three separate sessions to ensure that any patterns or trends detected are consistent. Often though, there may be many more sessions, exploring the subject area using different group compositions (e.g. with participants from different age groups or from different localities) and developing the content over time to explore different avenues. The method offers flexibility and can be used for many different purposes, including:

- obtaining general background knowledge for a new project, thus guiding the development of more detailed research, for example, the design of questionnaires;

- evaluating or gaining understanding and insight into results from other related research;

- gaining impressions and perceptions of existing or proposed services, products, programmes or organisations;

- stimulating new ideas or concepts.

The focused group interview was first used in the 1940s when social scientists used the technique to evaluate audience responses to radio programmes. The audience was asked to press red and green buttons whenever they heard anything that provoked a negative or positive response in them as they listened to the recording. At the end of the programme, the audience was asked to focus on the events they had recorded and to discuss the reasons for their reactions. Similar techniques were subsequently used to examine the effectiveness of wartime propaganda and training films. The history of focus groups is described in detail in Stewart and Shamdasani (1990), Morgan (1998) and Krueger (1994).

Focus group methods have been widely embraced by the marketing community, becoming one of the key tools employed by market researchers. The ability to gain in-depth understanding of users’ reactions is essential to those selling or providing products or services. Early feedback to new concept ideas can prevent expensive commercial disasters. Exploration of consumers’ attitudes and requirements can lead to product improvements or the development of lucrative new lines of products or services. The monitoring of consumers’ reactions to advertising, publicity material and packaging helps with the selection of the best approaches and contributes to improving overall effectiveness. Greenbaum (1998) provides examples of how focus groups are used in market research and, in Chapter 3 of this book, Wendy Ives explores the market researcher’s perspective in more detail.

Although the increase in the popularity of focus groups has largely been due to their use in market research, social scientists have continued to use them. Their applications range widely, for example: understanding public perceptions of mental illness; discovering reasons why individuals commit crimes; understanding participants’ conceptions of what causes heart attacks. Information gained from such studies helps to inform high-level policy decisions and allocation of public resources. Harbour and Kitzinger (1999) provide more examples of the use of focus groups in social science research projects.

1.4

THE ADVANTAGES OF FOCUS GROUPS

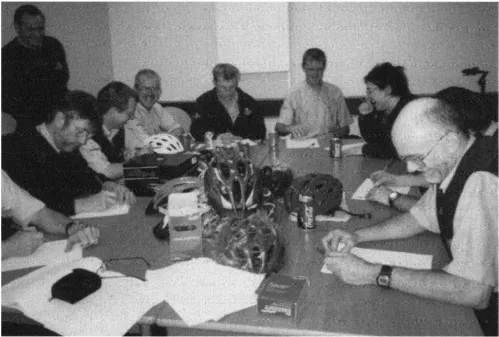

The focus group method is a qualitative research tool. Unlike trials, experiments and physical measurement methods, qualitative research cannot provide hard quantitative data that can be subjected to statistical or numerical analysis. The main strength of qualitative research though, is its ability to gain a more in-depth understanding of the topic being explored. It can more easily deal with information and concepts that cannot be readily measured or quantified, for example, the emotional relationships between user, tasks, products and systems. Qualitative research enables researchers to discover some of the reasons why people behave the way they do, or less tangible issues such as why people feel a certain way towards a product (see Figure 1.1) or task. Examples of qualitative data collection methods are informal discussions, structured interviews and open-ended questions as part of a questionnaire survey. The focus group is a kind of interview, but instead of being conducted on a one-to-one basis it is a collective interview with a group of people.

A key benefit of focus groups is that researchers interact directly with participants. The interviewer or moderator can explore the responses given to questions or comments and thus discover more about individuals’ perceptions and views. They can probe the accuracy of comments (maybe in response to nonverbal cues, such as gestures or facial expressions) and ask follow-up questions to clarify or qualify responses given. There is considerable flexibility so that, if necessary, questions can be added or modified in ‘real time’ to make the most of unexpected responses. Effective moderators can motivate participants to give more information and to participate fully where required. Also, face-to-face interaction enables the moderator to take account of the individual needs or characteristics of the participants and adjust their behaviour accordingly in order to encourage the information flow.

Figure 1.1 Focus groups can help to gain in-depth understanding—in this case to gain users’ feedback on cycle helmets (courtesy of Royal Mail)

The above could be said to apply to all interview techniques, but focus groups have an additional advantage in that the group members can react to and build upon the responses and comments of others. This synergistic effect often leads to the emergence of information or the creation of ideas that would otherwise not have occurred. In addition, being part of a group can generate a feeling of security. When participants learn that they are not alone in having to deal with a sensitive or difficult issue, they often speak openly and honestly in the discussions. This can lead to the discovery of information that may have remained hidden in a one-to-one situation.

Focus groups are applicable to a wide range of topic areas and types of people. This includes those who might not be able to readily take part in other forms of research, for example, children or people who are not very literate. Although they are sometimes conducted in specialist facilities, focus groups can take place in a wide variety of settings and with a minimum of supporting or expensive equipment. This means that, where necessary, the focus group can be taken to the participants rather than the other way round (see Martin Maguire’s example on financial services in Chapter 5). This is particularly helpful in cases where participants may find it hard to travel, for example, older or disabled people.

A great deal of information can be gained relatively efficiently and immediately with focus groups, particularly when compared with the equivalent time and effort required to gain a similar amount of information using individual interviews or postal surveys. The main reason for this is the group-based nature of the method. In just three or four sessions it is possible to gain views from a relatively large number of people-although care and time must be taken to recruit the most appropriate people using purposive sampling. The method is therefore fairly cost effective, although as Chapter 2 shows, running the sessions is the easy bit. There is a considerable amount of effort required beforehand to prepare the research and recruit participants, and then afterwards to analyse data and prepare reports. This should not be underestimated.

Both the concept of focus groups and the outcomes from them are easy for non-experts to understand. This is helpful when presenting results to others, including the sponsors of the research. The outputs are accessible because they can be presented in human terms. For example, the responses and comments of participants, whether written down as verbatim quotes, or presented in a video, are likely to be more easily understood than complex statistical analyses or tables of data. For this reason, the results of focus groups can be extremely powerful and persuasive—although this carries its own dangers, as discussed later.

1.5

THE DRAWBACKS AND LIMITATIONS

The strengths of the focus group method result from bringing together groups of individuals. Group settings, however, are more difficult to manage than one-to-one interactions and can lead to difficulties.

Discussion content. The discussion in a group interview is to a certain extent controlled by the group itself. What the group finds interesting to discuss may not be useful for the moderator’s research needs. If the discussion veers off into irrelevant areas, time is lost and the moderator has to intervene to bring things back on course. This can be very time consuming if it happens often. The make up of certain groups will mean that it will happen more frequently in some sessions than others.

Dominant group members. By their very nature, group discussions mean that the participants listen to and respond to each other, and are influenced by what they see and hear. Whilst this brings benefits, it can also cause problems because the outcomes may be steered in certain directions. In some cases, there is a danger that a dominant or highly opinionated member of the group may monopolise the discussions and significantly influence the views of other participants, thus skewing the findings. There can be problems too with quieter, more reserved participants who may be hesitant to contribute their views to the discussion.

Quality of the discussion. It is impossible to predict in advance how group make-up will influence the quality of the discussion. In some cases, the discussion will be lively, energetic and revealing. In others it might be slow and lethargic, providing little information of value

The presence of a skilled moderator can reduce the effect of all of the above problems, but they are unlikely to be completely eliminated. It is therefore important to plan sufficient separate sessions to provide confidence that the results are valid and consistent. If possible, it is also helpful to carry out research in parallel using different methods to triangulate the findings.

Focus groups generally rely on volunteer participants who are willing to put themselves out and take part in a session. For various reasons, certain types of people are unlikely to put themselves forward to take part, even with payment and other inducements. There is no guarantee, therefore, that those taking part are representative of a larger population, thus limiting the possibilities for generalisation of the outcomes. This, of course, is a drawback shared with many other research methods.

The objectivity of moderators is crucial. The moderator plays a key role in guiding and facilitating discussion and is a powerful member of the group. They can therefore bias the results by guiding the discussion in certain ways, or by knowingly or unknowingly providing cues which indicate desirable or undesirable responses. For focus groups concerning specialised areas (which is often the case in human factors/ergonomics and design) it is important that the moderator is knowledgeable enough to recognise discussion areas that could be beneficial to explore, and thus guide the discussion appropriately. Whilst it is possible to hire specialist moderators, it is likely that the best candidates for moderating such groups are the human factors/ergonomics researchers or designers themselves. It is thus important that they develop their moderation skills.

Focus groups cannot totally reflect real-life scenarios. The sessions are conducted in places and at times that are removed from the actual places and times where people have the experiences explored in the discussions. In effect, the participants have to remember or visualise experiences for the discussion, with few ‘triggers’ to help stimulate them. This can limit the quality of the outputs, as discussed by Peter Coughlan and Aaron Sklar in Chapter 8, so it is important to provide appropriate stimuli and prompts. In addition to this, there are sometimes marked differences between what participants say they do, and what they actually do in practice. The moderator may have to probe more deeply, or approach the same subject from several different angle...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Acknowledgements

- Contributors

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Part I: Organising and Conducting a Focus Group: The Logistics

- Part II: Focus Groups in Human Factors/Ergonomics and Design Case Studies

- Part III: Focus Group Tools

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Focus Groups by Joe Langford,Deana McDonagh in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Project Management. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.