This is a test

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Atlas of U.S. and Canadian Environmental History

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This visually dynamic historical atlas chronologically covers American environmental history through the use of four-color maps, photos, and diagrams, and in written entries from well known scholars.Organized into seven categories, each chapter covers: agriculture * wildlife and forestry * land use and management * technology and industry * polluti

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Atlas of U.S. and Canadian Environmental History by Char Miller in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Historia del mundo. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

European Exploration and the Colonial Era

(1492–1770s)

J ohn Smith, an English explorer who journeyed to the New World in the early seventeenth century, was a legend in his own mind. His General History of Virginia (1624) offers a much-revised account of how he led his fellow Jamestown, Virginia, colonists through the many hardships they endured to establish the settlement in the early 1600s. Despite its vainglorious quality, Smith’s book, which he wrote after he returned to England in 1609, is a firsthand and vivid depiction of the interactions between indigenous peoples and the invading English settlers. As he identifies the sharp disparities between the two peoples’ civilizations and level of technological development, he also catalogs the region’s astonishing wealth of natural resources. He mapped many of its rivers and bays, noted the rich, well-watered soil, and praised the thick stands of timber.

The book’s descriptions of the economic wealth of the landscape were designed to appeal to English readers who might invest in or immigrate to the colony. This appeal was heightened by Smith’s mouthwatering descriptions of the natural abundance of food. As winter approached, he wrote, “the rivers became so covered with swans, geese, ducks and cranes that we daily feasted with good bread, Virginia peas, pumpkins, and persimmons, fish, fowl, and divers sorts of wild beasts as fat as we could eat them.”

In dangling such sumptuous fare before his readers, Smith was contributing to the emergence of a colonial literature that contrasted New World vitality with Old World weariness. His claims would be confirmed by subsequent generations of settlers in British North America, New France, and New Spain. Along the Atlantic seaboard, hundreds of settlements would spring up that would enjoy rapid and consistent population growth, develop a very productive agricultural and commercial economy, and build busy port cities whose trade networks extended around the globe.

Natural Resources. Early English and French colonists were both overwhelmed by and eager to exploit the vast forests they encountered and the variety of wildlife that lived within North America’s woods. As with the indigenous peoples of the continent, the settlers made full use of this great plenty, searching for berries and nuts, hunting game, and burning and logging forests to create more open space. Unlike Native Americans, they let their domesticated animals, cattle, hogs, and sheep, forage freely in the woods, an easy way to feed the expanding numbers of animals and to eliminate forest cover.

Despite their cultural differences, all Europeans believed in the concept of private property and the necessity of constructing agricultural landscapes. The key material for their built environments was wood. Because of their large numbers, the English colonists consumed vast quantities for housing, fencing, and fuel. This demand sparked the development of a complex lumber business that cleared lands far beyond the population centers. The profit from this trade was reinvested in new lands, contributing to rapid deforestation and the spread of a farm-based economy in what is now the eastern United States and Canada.

European Settlements. The English communities grew swiftly; by the mid-eighteenth century, more than 1.5 million English lived in the New World, compared with seventy thousand French settlers, and even fewer Spanish. Each group established different patterns of land use. The “Little Commonwealths” of New England were small towns built on the open-field system that granted individual settlers house lots, as well as rights to and responsibilities for common meadows and woodlots. Few towns existed in the southern Chesapeake Bay tobacco colonies, which developed around large-scale plantation agriculture that used slave labor to plant and harvest the crop, and river transportation to take it to market. Dependent on rivers, too, were the New France settlements in Canada. Under the feudal seigneurial system, narrow strips of land along the riverfront were parceled out to the Roman Catholic church and to elite individuals, who could either sell the property or rent it to tenants.

Far to the south and west, Spanish settlements formed around Roman Catholicism had also been established. Missionaries and civilian leaders worked with military forces to conscript local Native American populations into the labor force to clear agricultural land, dig irrigation ditches, and construct communal and religious buildings. The physical expanse of New Spain, which stretched from present-day California to Florida, resulted in the Spanish towns often being so far from one another, and from the larger cities of central Mexico, that they remained small in population and limited in economic import.

Interactions with Native Americans. Unlike other European New World settlers, the Spanish interacted more freely with indigenous peoples, culturally and sexually, leading to the creation of a mestizo, or mixed, population. The English, by contrast, had no desire to mix with members of local Native American tribes; they saw themselves as a more advanced culture that was in direct competition with indigenous peoples for land and resources. Open conflict between these settlers and Native Americans intensified by the mid-eighteenth century as the English pushed beyond the Appalachian Mountains, where they replicated patterns of settlement and resource exploitation that they had employed along the Atlantic seaboard. The French, whose numbers were smaller and expansionary desires more muted, did not come into as much conflict with Native Americans.

Regardless of their motives or perspectives, the three major colonial powers in the New World forever changed Native American culture. The swelling European birthrate and immigration to the New World, when combined with the superiority of Europe’s military technology, enabled settlers to extend their control over the land and its many resources. Despite the destructive impact of immigration and settlement on the indigenous human populations and on native flora and fauna, the Europeans brought different foods and animals that “Europeanized” North America, while concurrently influencing the cultures and diets of England, France, and Spain.

This so-called Columbian Exchange was not equal in its impact. Even before large-scale settlement, Old World diseases that European explorers and fishermen brought with them had devastated indigenous peoples who lacked immunity to measles and smallpox. Had the daring Captain John Smith been able to return to Virginia at the close of the eighteenth century, he would have been astounded by how thoroughly his dream of continental conquest had come to pass.

—Char Miller

Columbian Exchange

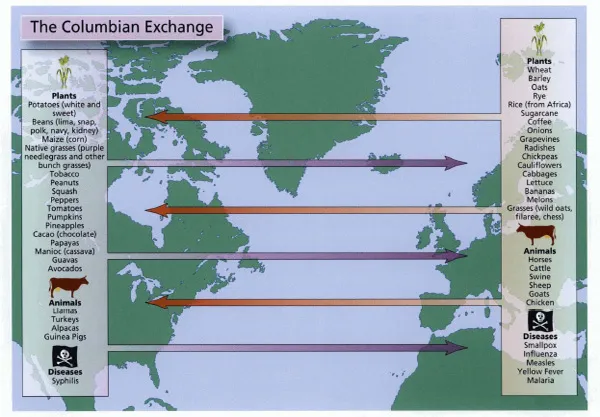

T he Columbian exchange refers to the exchange of plants between the Old and New Worlds and the introduction of animals from Europe to the Western Hemisphere following the arrival of Europeans in the fifteenth century. By introducing a host of crop plants and domesticated animals to their new environment, the Spanish, French, and British settlers attempted to “Europeanize” the North American continent. Beginning with the second voyage of Columbus in 1493, the Spanish introduced wheat, melons, onions, sugarcane, grapevines, radishes, chickpeas, cauliflowers, cabbages, and lettuce, as well as horses, cattle, swine, sheep, goats, and chickens. This voyage began the exchange of plants and animals between the New and Old Worlds that would have significant effects on the environments and ecologies of both worlds.

Diseases. The Columbian exchange also spread Old World diseases, such as smallpox, influenza, and measles, among the indigenous populations—none of which had immunity to those diseases. Along the Atlantic coast of Canada, for example, fishermen and fur traders exposed indigenous peoples to European diseases during the early sixteenth century. During the seventeenth century, diseases decimated Native American populations in present-day New England, while during the eighteenth century Russian explorers spread diseases among the Aleut, Eskimo (Inuit), and Tlingit in the Pacific Northwest. Although the Old World diseases introduced in the New World were often catastrophic to indigenous populations, the Columbian exchange brought nutritional benefits and improved food supplies with the addition of new crops and new animal species.

The exchange of flora between the New and Old Worlds was extensive by the seventeenth century. By the late eighteenth century, many agricultural plants had been traded, particularly between the Western Hemisphere and Europe and Africa. Although some native animals from the New World, such as turkeys and llamas, were introduced in Europe, the exchange of fauna for agricultural purposes was primarily from Europe to the New World.

Sources: James Lang, Notes of a Potato Watcher (College Station: Texas A & M University Press, 2001), 21; Elaine N. McIntosh, American Food Habits in Historical Perspective (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1995), 65; and The Columbian Biological Exchange. Dr. Harold D. Tallant, Department of History, Georgetown College. 3 Dec. 1998. <http://spider.georgctowncollege.edu/htallant/courses/his111/columb.him>.

Plants. By 1500, the Spanish (see also 16–17) had made considerable progress in their attempt to transform the New World into the Old World; by the mid-sixteenth century the process was irreversible. Spanish settlers at St. Augustine in present-day Florida raised oranges by 1579. By 1660, Spanish farmers or their subjects in Mexico cultivated nearly all of the most important food plants from the Old World, including wheat, barley, oats, and rye. Slaves or slave traders introduced the African crop of rice to the Carolina lowlands by the early 1670s. Rice enabled white planters on the sea islands and low coastal plain to cultivate swamplands, while wheat and barley permitted settlers in the present-day United States and Canada to cultivate lands too high, dry, or cool for growing maize (corn) and other native crops in significant quantity.

Animals. The introduction of animals from the Old World was more significant in the use of the environment than the influx of new plants. By 1500, the major breeds of cattle and horses had arrived from Spain, which enabled New World people to use the environment in a different way by converting grass grazed by animals into meat, milk, and cheese. Spanish hogs and cattle readily adapted to their new environment. In 1539 Hernando de Soto began exploring present-day Florida, taking thirteen hogs to help feed his men. By the time of his death in 1542, they had multiplied to a herd of seven hundred.

Spanish horses also bred rapidly and, along with disease, moved faster across the North American continent than the people who brought them. By 1700, the Plains tribes south of the Platte River in present-day Nebraska were familiar with horses; by 1750, the tribes north of the river were also routinely using horses. During the mid-1780s, horses grazed on the banks of the Saskatchewan River in present-day Saskatchewan. On the North American plains horses revolutionized transportation, hunting, and war, particularly for Native Americans like the Sioux, Cheyenne, and Comanche.

Further Reading

Crosby, Alfred W., Jr. The Columbian Exchange: Biological and Cultural Consequences of 1492. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1972.

Lang, James. Notes of a Potato Watcher. College Station: Texas A & M University Press, 2001.

McIntosh, Elaine N. American Food Habits in Historical Perspective. Westport, Conn.: Pracger, 1995.

Smith, Andrew F. The Tomato in America: Early History, Culture, and Cookery. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2001.

Concurrently, sheep arrived in the American Southwest, soon outnumbered cattle, and became important sources of food and skins. The Navajo were particularly successful at adapting sheep into their culture and environment, and they became great herders on the arid grazing lands of the Southwest. By the early eighteenth century Spanish longhorn cattle roamed the grasslands of present-day southern Texas, easily adapting to the hot, dry climate. Cattle also became a new food source for some Apache bands that stole them from the Spanish ranchers in that region. In some areas, cattle, horses, and sheep required large grazing areas and frequently strayed into Native Americans’ fields and damaged crops.

Impact. Although Old World diseases decimated native populations in the New World, the introduction of Old World plants and animals, particularly horses and cattle, and the adoption of New World corn by European settlers contributed to population growth and more extensive use of the land for agricultural purposes. European plants and animals significantly increased food variety, supply, and nutrition, particularly in the addition of animal protein, to New World populations. The great variety of European food plants enabled settlers to adapt quickly to their new environment.

In the New World, these plant and animal introductions readily adapted to the environment. Horses, cattle, and particularly sheep enabled Native Americans and immigrants to use the lands of the arid Southwest and semiarid Great Plains. However, in the absence of natural predators, cattle, horses, and sheep occasionally overgrazed grasslands, eventually contributing to soil erosion, the elimination of native grasses, and the invasion of weeds such as dandelions. Newly introduced Spanish grasses had a high tolerance for drought and overgrazing, which made them perfectly suited for the dry Southwest. Eventually these grasses, for example, wild oats, filaree, and chess, competed with and forced out native grasses like purple needlegrass and other bunch grasses. Although Spanish grasses contributed to greater flora diversity on the North American continent, some native grasses became threatened with extinction.

The Columbian exchange had other environmental consequences. Many indigenous New World plants that had been domesticated by Native Americans were ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Chapter One: European Exploration and the Colonial Era (1492–1770s)

- Chapter Two: Expansion and Conflict (1770s–1850s)

- Chapter Three: Landscape of Industrialization (1850s–1920s)

- Chapter Four: The Conservation Era (1880s–1920s)

- Chapter Five: From the Depression to Atomic Power (1930s–1960s)

- Chapter Six: The Rise of the Environmental Movement (1960s–1980s)

- Chapter Seven: Contemporary Environmentalism (1980s–Present)

- Timeline

- Bibliography

- List of Contributors

- Index