eBook - ePub

Pharmacy Practice

This is a test

- 561 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Pharmacy Practice

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Today's pharmaceutical services are patient-oriented rather than drug-oriented. This shift towards patient-centred care comes at a time when healthcare is delivered by an integrated team of health workers. Effective pharmacy practice requires an understanding of the social context within which pharmacy is practised, recognising the particular needs

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Pharmacy Practice by Kevin M. G. Taylor, Geoffrey Harding, Kevin M. G. Taylor, Geoffrey Harding in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Médecine & Pharmacologie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

The Development of Pharmacy Practice

1

The Historical Context of Pharmacy

Stuart Anderson

INTRODUCTION

Why is pharmacy practised in the way it is today? Has the dispensing of prescriptions always been the main activity in community pharmacy? How did multiples come to dominate community pharmacy in Britain, but not in other countries? Could pharmacy practice just as easily have developed very differently? The answers to these questions are to be found in pharmacy’s history, from its origins in the mists of time to the diversity of practice that is pharmacy today.

This chapter has three objectives: to define the main ‘time frames’ (periods bounded by key events) within the history of pharmacy; to describe the key ‘watersheds’ (the defining events) in that history; and to examine the impact which these events have had on the practice of pharmacy. Following a general account of the evolution of pharmacy, the chapter focuses on developments in Britain, illustrating the balance of social, political, economic and technological factors that determine the nature of pharmacy practice in all countries.

THE ORIGINS OF PHARMACY UP TO 1841

The dawn of pharmacy, Antiquity to 50 BC

The nature of the earliest medicines is lost in the remoteness of history. Cavemen almost certainly rolled the first crude pills in their hands. Pharmacy, as an occupation in which individuals made a living from the sale and supply of medicines, is amongst the oldest of professions. The earliest known prescriptions date back to at least 2700 BC and were written by the Sumerians, who lived in the land between the Euphrates and Tigris rivers. The practitioners of healing at this time combined the roles of priest, pharmacist and physician.

Chinese pharmacy traces its origins to the emperor Shen Nung in about 2000 BC. He investigated the medicinal value of several hundred herbs, and wrote the first Pen T’sao, or native herbal, containing 365 drugs. Egyptian medicine dates from around 2900 BC, but the most important Egyptian pharmaceutical record, the Papyrus Ebers, was written much later, in about 1500 BC. This is a collection of around 800 prescriptions, in which some 700 different drugs are mentioned. Like the Sumerians, Egyptian pharmacists were also priests, and they learnt and practised their art in the temples.

The emergence of pharmacy, 50 BC to 1231 AD

It was more than another thousand years before the early Greek philosophers began to influence medicine and pharmacy. They not only observed nature, but sought to explain what they saw, gradually transforming medicine into a science. The traditions of Greek medicine continued with the rise of the Roman Empire. Indeed, the greatest physicians in Rome were nearly all Greek. The transition of pharmacy into a science received a major boost with the work of Dioscorides in the first century AD. In his Materia Medica he describes nearly 500 plants and remedies prepared from animals and metals, and gives precise instructions for preparing them. His texts were considered basic science up to the sixteenth century.

Perhaps the greatest influence on pharmacy was Galen (130 to 201 AD), who was born in Pergamos and started his career as physician to the gladiators in his home town. He moved to Rome in 164 AD, eventually being appointed as physician to the imperial family. Galen practised and taught both pharmacy and medicine. He introduced many previously unknown drugs, and was the first to define a drug as anything that acts on the body to bring about a change. His principles for preparing and compounding medicines remained dominant in the Western world for 1,500 years, and he gave his name to pharmaceuticals prepared by mechanical means (galenicals).

The first privately owned drug stores were established by the Arabs in Baghdad in the eighth century. They built on knowledge acquired from both Greece and Rome, developing a wide range of novel preparations, including syrups and alcoholic extracts. One of the greatest of Arab physicians was Rhazes (865–925 AD) who was a Persian born near Tehran. His principal work, Liber Continens, was to play an important part in Western medicine. He wrote ‘if you can help with foods, then do not prescribe medicaments; if simples are effective, then do not prescribe compounded remedies’.

These new ideas became assimilated into the practice of pharmacy across western Europe following the Moslem advance across Africa, Spain and southern France. Perhaps the greatest figure in the science of medicine and pharmacy during this period was the Persian, Ali ibn Sina (980 to 1037 AD), who was known by the western world as Avicenna. He was the author of books on philosophy, natural history and medicine. His Canon Medicinae is a synopsis of Greek and Roman medicine. His teachings were treated as authoritative in the West well into the seventeenth century and they remain dominant influences in some eastern countries to this day. The figures of Avicenna and Galen appear in the Coat of Arms of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain (Figure 1.1).

The separation of pharmacy from medicine: the edict of Palermo 1231

In European countries exposed to Arab influence, pharmacy shops began to appear around the eleventh century. Frederick II of Hohenstaufen, who was Emperor of Germany and King of Sicily, provided a key link between east and west, and it was in Sicily and southern Italy that pharmacy first became legally separated from medicine in 1231 AD. At his palace in Palermo, Frederick presented the first European edict creating a clear distinction between the responsibilities of physicians and those of apothecaries, and he laid down regulations for their professional practice.

Figure 1.1 The coat of arms and motto of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. Note the figures of Avicenna (left) and Galen (right). The motto is commonly but incorrectly translated as ‘We must pay attention to our health’.

Reproduced with permission of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain.

Frederick’s decree provided the basis of similar legislation elsewhere. The Basle Apothecaries Oath, for example, drawn up in 1271, spelled out the relationship between physicians and apothecaries. It stated that ‘no physician who cares for or has cared for the sick shall ever own an apothecary’s business in Basle, nor shall he ever become an apothecary’. In other European countries, pharmacy emerged as a separate occupation over the centuries which followed. German pharmacists, for example, formed themselves into a society in 1632.

The first official pharmacopoeia, to be followed by all apothecaries, originated in Florence. The Nuovo Receptario, published in 1498, was the result of collaboration between the Guild of Apothecaries and the Medical Society, one of the earliest examples of the two professions working constructively together.

The medicalisation of the apothecary

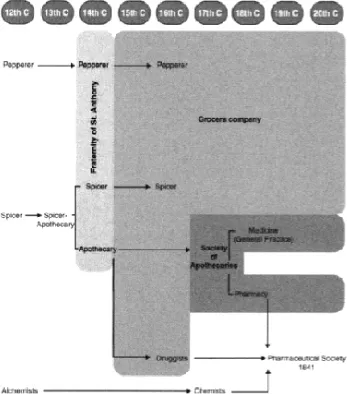

In most European countries, the apothecary or pharmacist developed from pepperers or spicers. The evolution of the English apothecary and pharmacist from the twelfth to the nineteenth centuries is illustrated in Figure 1.2. Traders in spicery, which included crude drugs and prepared medicines, evolved into either grocers or apothecaries. By the thirteenth century, apothecaries formed a distinct occupational group in many countries, including England and France.

During the Middle Ages the evolution of French and British pharmacy was almost identical. In due course, the French apothicaire developed into the pharmacien, whilst the English apothecary became a general medical practitioner. In Britain, trade in drugs and spices was monopolised by the Guild of Grocers, who had jurisdiction over the apothecaries. However, the apothecaries formed an alliance with court physicians, and they succeeded in persuading James I to grant a Charter in 1617 to form a separate company, the Society of Apothecaries. This was the first organisation of pharmacists in the Anglo-Saxon world.

Figure 1.2 The evolution of pharmacy in Great Britain, twelfth century to 1841.

Source: Trease (1964).

The apothecaries were both physicians (but not surgeons) and pharmacists, diagnosing and dispensing the medicines which they themselves prescribed. There were, however, other groups involved in the sale and supply of medicines, the chemists and druggists. The Apothecaries Act of 1815 confirmed apothecaries as physicians, and laid down the training required to practise as such. Most apothecaries subsequently opted to practise exclusively as general medical practitioners, and an opportunity was presented to the other groups whose business was the sale and supply of medicines.

The organisation of pharmacy

In France, the pharmacien received official recognition with the establishment of the College de Pharmacie in 1777, which ushered in modern French pharmacy. During the 17th and 18th centuries many people in continental Europe passed the examinations for both pharmacy and medicine, and practised both. In some countries, developments took place on a regional basis. In Italy, for example, Austrian regulations for the Lombardy district in 1778 provided the stimulus for changes in pharmacy practice in the north of the country. But it was only after the establishment of the new Italian Kingdom in 1870 that uniform arrangements were established across Italy.

In Germany, pharmacists in Nuremberg formed themselves into a society as early as 1632. A regional organisation for north Germany was formed in 1820, and for southern Germany in 1848. After the federation of German states, these two societies amalgamated to form a national German pharmacists’ society, the Deutscher Apothekerverein, in 1872. A few years later, in 1890, the Deutsche Pharamzeutische Gesellschaft was established to promote pharmaceutical science and research. Early American pharmacy was heavily influenced by immigrants from Europe. An Irish apothecary, Christopher Marshall, established the first such shop in Philadelphia in 1729. The American Pharmaceutical Association, open to ‘all pharmaceutists and druggists of good character’, was established some time later, in 1852.

International cooperation between pharmacists has a long history. It had long been a dream of many pharmacists to establish an international pharmacopoeia. German pharmacists took the initiative to convene the first International Congress of Pharmacy, which took place in Braunschweig, Germany in 1865. International congresses continued to be held every few years in different countries, but there was no formal mechanism for international contact. It was the Dutch Pharmaceutical Association that proposed at the tenth congress in 1910 that a permanent association be formed. The International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP), with headquarters and secretariat at The Hague, was founded in 1911, when the first meeting of delegates from around the world took place.

THE PROFESSIONALISATION OF PHARMACY, 1841 TO 1911

It is with the foundation of the Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain in 1841 that the modern history of British pharmacy begins. The seventy years leading up to the beginnings of the welfare state in 1911 were a time of rapid social change which saw the increasing professionalisation of many occupations, including pharmacy. This section focusses on four developments: the foundation of the Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain; pharmacists’ education and qualifications; the origins of the multiples in pharmacy; and the nature of practice during this period.

The foundation of the Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, 1841

Early in 1841, a Mr Hawes introduced a Bill to Parliament that would have made it compulsory for chemists and druggists to pass an examination before being able to carry on their business. If they bandaged a finger or recommended a remedy they would be deemed to be practising medicine, and hence would need to be medically qualified. The leaders of the chemists and druggists took action, and on April 15, 1841 a small group met at the Crown and Anchor Tavern in the Strand in London. They included William Allen FRS, John Savory, Thomas Morson, and Jacob Bell, the son of a well-known Quaker chemist and druggist, John Bell.

William Allen moved a resolution that ‘an Association be now formed under the title of The Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain’. It was seconded by John Bell and carried by the meeting. The Society was to have three objectives:

‘To benefit the public, and elevate the profession of pharmacy, by furnishing the means of proper instruction; to protect the collective and individual interests and privileges of all its members, in the event of any hostile attack in Parliament or otherwise; and to establish a club for the relief of decayed or distressed members’.

At its foundation, the Society was to consist of both members and associates. Full membership was restricted to chemists and druggists who owned their own businesses. Pharmacy managers, or assistants, even those who had passed the major examination, could only become associates. Nevertheless, by the end of 1841 the new society had around 800 members, and by May of 1842 membership had risen to nearly 2,000. In December 1841 it acquired 17 Bloomsbury Square, London, as its headquarters. It was to remain there until September 1976. Jacob Bell began a series of monthly scientific meetings at his own home, and in July 1841 he published The Transactions of the Pharmaceutical Meetings, later to be re-titled the Pharmaceutical Journal. The Society gained legal recognition with its incorporation by Royal Charter in 1843.

Pharmacists’ education and qualifications

From its foundation, one of the main priorities of the Pharmaceutical Society was the setting up of an examination system and a school of pharmacy. The examination system consisted of an entrance requirement, followed by the Minor examination, which was taken at the end of a four or five year apprenticeship. To become a full member the associate was required to take the more advanced Major examination. Apprentices and assistants were advised to attend appropriate lectures, but the opportunities to do so were few. The Society set up its own School of Pharmacy within its Bloomsbury Square headquarters in 1842, but this was only available to those with ready access to London.

Branch schools were opened in Manchester, Norwich, Bath and Bristol in 1844, and in Edinburgh soon afterwards. After 1868, privately owned schools of pharmacy began to appear. In 1870 there were seven, only two of which were outside London. But by 1900 the number of schools offering courses in pharmacy had reached fortyfive. The number of schools of pharmacy in Britain between 1880 and 1963 is illustrated in Figure 1.3. The last privately-owned school, in Liverpool, closed in 1949.

The first Register of Pharma...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Foreword

- Contributors

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- PART ONE: The Development of Pharmacy Practice

- PART TWO: International Dimensions of Pharmacy Practice

- PART THREE: Health, Illness and Medicines Use

- PART FOUR: Professional Practice

- PART FIVE: Meeting the Pharmaceutical Care Needs of Specific Populations

- PART SIX: Measuring and Regulating Medicines Use

- PART SEVEN: Research Methods