eBook - ePub

Experiencing Food: Designing Sustainable and Social Practices

Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Food Design and Food Studies (EFOOD 2019), 28-30 November 2019, Lisbon, Portugal

Ricardo Bonacho,Maria José Pires,Elsa Cristina Carona de Sousa Lamy

This is a test

- 165 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Experiencing Food: Designing Sustainable and Social Practices

Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Food Design and Food Studies (EFOOD 2019), 28-30 November 2019, Lisbon, Portugal

Ricardo Bonacho,Maria José Pires,Elsa Cristina Carona de Sousa Lamy

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Experiencing Food: Designing Sustainable and Social Practices contains papers on food, sustainability and social practices research, presented at the 2nd International Conference on Food Design and Food Studies, held November 28-30, 2019, at the Faculty of Architecture, University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal. The conference and resulting papers reflect on interdisciplinarity as not limited to the design of objects or services, but seeking awareness towards new lifestyles and innovative approaches to food sustainability.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Experiencing Food: Designing Sustainable and Social Practices an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Experiencing Food: Designing Sustainable and Social Practices by Ricardo Bonacho,Maria José Pires,Elsa Cristina Carona de Sousa Lamy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Food Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Introduction of seaweeds in desserts: The design of a sea lettuce ice cream

B. Moreira-Leite, J.P. Noronha & P. Mata

LAQV, REQUIMTE, Departamento de Química, Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia, Universidade Nova de Lisboa (FCT/UNL), Caparica, Portugal

ABSTRACT: Marine macroalgae are complete foods through a nutritional point of view, however studies in the context of phycogastronomy are scarce. The present work intends to discuss the design and validation process of a novel food product made using the seaweed “sea lettuce” (Ulva sp.). First instrumental and sensory analyses of the seaweed were carried out to build a flavor profile. Then, an ice cream was formulated, evaluated by a focus group, and finally it was applied in high gastronomy dessert. Results of the analyses show that some algae, if properly processed and worked in the best way, have a potential to be introduced into various food products and recipes, including pastry formulations.

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Seaweeds

Algae are unicellular or pluricellular, photoautotrophic organisms that live in water or moist environments, with chlorophyll as the primary photosynthetic pigment. Unlike plants, there is no sterile cover in its reproductive cells (Lee, 2008). Algae form a diverse group of organisms that are differentiated by their size, color and morphology (Pereira, 2009).

Seaweeds are marine macroalgae consumed as vegetables in Japan and China for more than fifteen centuries. Its regular consumption occurs mainly in East Asia and island regions located in the Pacific Ocean. In a less extent, they are also consumed in Chile, some Northern European and Nordic countries (Pereira, 2016).

Nowadays it is possible to observe an increasing interest of the Western World – for example, North America, Iberian Peninsula and some of the European countries previously mentioned – in seaweed consumption mainly due to its alleged health benefits (Buschmann et al., 2017; Mouritsen, 2013). Another plausible explanation is the emergent use of seaweeds by chefs, which have the power of influencing people to adopt this ingredient as a food source (Mouritsen, 2012; Rioux et al., 2017).

Due to its high nutritional features, seaweeds have a great potential to be applied in food formulations: they are rich in proteins and dietary fibers, an excellent source of vitamins, minerals and trace elements, and are poor in sugars and lipids – having mainly polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), ω-3 (EPA and DHA) and ω-6 (AA) 3, in balance – which results in a low caloric intake (Mišurcová, 2012; Mouritsen, 2012).

Some of the advantages of seaweeds over other possible dietary sources are high protein levels (dry weight), rapid growth and productivity, onshore or offshore (which makes up about 70% of the earth surface) production, either alone or together with other marine organisms, in integrated multi-trophic aquaculture (IMTA) systems. Unlike livestock, one of the activities that most contributes to global warming, aquaculture of algae allows to convert carbon dioxide into biomass through photosynthesis, releasing oxygen into the atmosphere, with the advantage of not competing with other food crops for land or water (Buschmann et al., 2017).

1.2 Phycogastronomy

Phycogastronomy is a term that derives from the Greek suffix “phukos”1 (ϕύκoς) which means seaweed; and the word “gastronomy”2, used to refer to the “study of the laws of the stomach” and that nowadays should be interpreted as the “art or science of choosing, cooking, and eating good food” (Rentera, 2007). Thus, it can be inferred that “phycogastronomy” is the art of preparing and cooking seaweed in the best way, taking advantage of its nutritional potential and enhancing or improving its organoleptic properties.

According to algaeBASE3 there are around 10,500 catalogued species of which approximately 1500 are green, 7000 are red and 2000 are brown. However, only a small part (± 221 species) of these are considered edible and only 145 species are directly used in culinary preparations. Many edible seaweeds are also used for industrial purposes such as hydrocolloids extraction (Pereira & Correia, 2015).

Seaweeds (or sea vegetables) are highly versatile ingredients, allowing to make all sorts of preparations: drinks (specially teas), snacks, pastries, breads, salads, omelets, soups, stews and desserts, among others. They may also be used as seasoning, garnish or main ingredient (Pereira, 2016).

The seaweed “sea lettuce” (Ulva sp.) is characterized by the intense aroma of sea with some green notes, and should be consumed fresh, only hydrated or quickly cooked. It replaces very well leafy vegetables in salads, soups, stir fries and stews. In the Azores, this species is used in the confection of soups and “tortas”, a sort of omelet (Mouritsen, 2013; Pereira, 2016).

1.3 Ice cream

The term “ice cream” can be applied to many different types of frozen dessert. These desserts have in common the fact that they contain ice crystals and are sweet, flavored, and usually eaten in the frozen state. Ice cream is frequently classified as premium, standard or economy. Premium ice cream is typically made from good quality ingredients, having a high amount of dairy fat and a low overrun (amount of air incorporated), whereas economy ice cream is made from low cost ingredients (for example, vegetable fat or oils) and up to 50% of the volume in air (Clarke, 2004).

The ice cream is a complex colloidal system comprised of a disperse phase of ice crystals (sol), air bubbles (foam) and fat droplets (ranging from 1 μm to 0.1 mm and forming an emulsion) and a continuous phase, also known as the matrix, made of a viscous solution of dissolved sugars, polysaccharides and milk proteins. The science of ice cream consists of understanding its ingredients, methods of preparation, microstructure and texture (as well as how these are connected). The ingredients and processing methodology create the microstructure that has a huge impact on the perceived texture. The solution coats the numerous ice crystals allowing them to bind smoothly to each other. The size of the ice crystals defines the creaminess of the ice cream, with larger crystals imparting a coarse or grainy texture, for example. The air bubbles dispersed in the ice cream weaken the matrix, making the ice cream lighter and allowing it to be eaten at low temperatures. In order to understand “one of the most complex food colloid of all” it is necessary to resort to many scientific disciplines (Clarke, 2004; Mcgee, 2004).

2 SEA LETTUCE FLAVOR PROFILE

2.1 Seaweed sensory analysis

A focus group with trained tasters, carried out in the context of a previous work (Moreira Leite, 2017), associated the flavor of the fresh “sea lettuce” with the aroma profile of fresh cut grass, green tea, seashore air and cooked cabbage or canned corn. Through sensory analysis tests of a cooked semolina pasta enriched with dried “sea lettuce”, done by untrained tasters and using the “Check-All-That-Apply” (CATA) methodology, the following attributes were associated with the developed product: seaweed flavor and aroma, sea flavor and seashore aroma (Moreira Leite, 2017).

These similar, but distinct, results show how sensitive are the volatile organic compounds (VOCs) present in the “sea lettuce”. In fact, a series of chemical reactions start taking place the moment the macroalgae are removed from its natural environment (Maarse, 1991). This makes seaweeds very delicate ingredients that can be easily affected by storage conditions, preserving and cooking methods (Le Pape et al., 2002; Shu & Shen, 2012).

2.2 GC–MS analysis

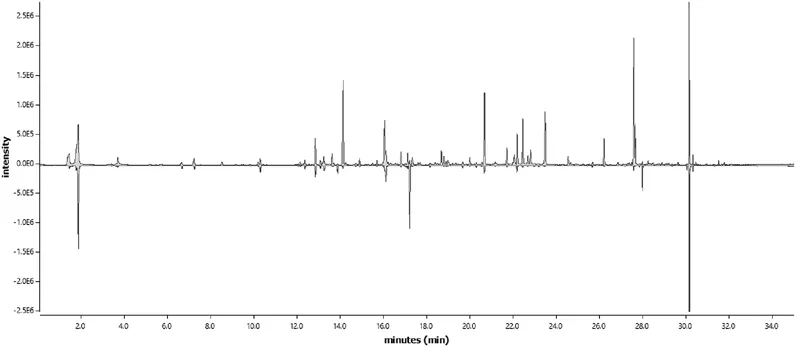

Analysis by gas chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry (GC–MS) showed that the volatiles profile changes with the conservation technique applied to the seaweed as emphasized in the previous section (Moreira Leite, 2017).

In Figure 1, a mirrored chromatogram of the fresh (above) and dried (below) “sea lettuce” is presented. It can be clearly seen that the seaweed loses some aromatic complexity when undergoing heat treatment4, especially regarding to the presence of ketones and alcohols. In terms of aroma profile, this means that the samples changed from fresh, green, fatty and earthy notes to a more marine (sulfuric) and citric scent (Moreira Leite, 2017). These changes are the result of chemical reactions induced by thermal, autoxidation or enzymatic activities in which compounds as Dimethyl sulfide (DMS) and Nonanal are produced (Fujimura & Kawai, 2000; Maarse, 1991).

Figure 1. Chromatograms of the fresh (above) and dried (below) “sea lettuce”.

2.3 Sea lettuce vs. green tea

Results of studies about volatile components in green tea reveals that it shares many VOCs with the “sea lettuce” (Ho et al., 2015; Maarse, 1991; Yang et al., 2018): 12 of the 14 VOCs identified in the dried sample5 and 17 of the 25 VOCs identified in the fresh seaweed6. Except for the presence of some aliphatic acids, not identified in the GC–MS analysis due to extraction characteristics and methodology, in general the aroma of tea is related to the abundance of aldehydes, ketones, and alcohols presents. The key compounds for the characterization of the green tea seem to be (E, E)-2,4-Heptadienal, Nonanal and β-Ionone. The last two chemical compounds are possibly, along with DMS, primarily responsible for th...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Committee members

- Food design methods to inspire the new decade. Agency-centered design. Toward 2030

- Designing with a fork: Lessons from past urban foodscapes for the future

- Feeding new alternatives: Reducing plastic in the take-away industry

- Food system photographic portraits: A necessary urban design agenda

- Gastronomic potential and pairings of new emulsions of vegetable origin

- #Foodporn vintage, food depiction – from symbolic to desire

- Where interaction design meets gastronomy: Crafting increasingly playful and interactive eating experiences

- Sustainability on the menu: The chef’s creative process as a starting point for change in haute cuisine (and beyond)

- ‘Squid Inc’: Designing transformative food experiences

- Beyond product-market fit: Human centered design for social sustainability

- Designing menus to shape consumers’ perception of traditional gastronomy: Does it work for the Portuguese Alentejo cuisine?

- Seaweeds: An ingredient for a novel approach for artisanal dairy products

- Introduction of seaweeds in desserts: The design of a sea lettuce ice cream

- From industry to the table: The tableware sector in Portugal

- Designing grassroots food recovery circuits in urban Romania

- Food Design Dates: Design-under-pressure activities in a cross-cultural and multidisciplinary online collaboration

- Development of dishes free from the main food allergens – a case study

- Integrating and innovating food design and sociology – healthy eating

- Design, short food supply chain and conscious consumption in Rio de Janeiro

- From Asia to Portugal – fermentation, probiotics and waste management in restaurants

- The experience of the natural world in a moment of fine dining – interwoven approaches to sustainability

- Floating dish, a sustainable, interactive and fine dining concept

- Author index

Citation styles for Experiencing Food: Designing Sustainable and Social Practices

APA 6 Citation

Bonacho, R., Pires, M. J., & Lamy, E. C. C. S. (2020). Experiencing Food: Designing Sustainable and Social Practices (1st ed.). CRC Press. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/1712864/experiencing-food-designing-sustainable-and-social-practices-proceedings-of-the-2nd-international-conference-on-food-design-and-food-studies-efood-2019-2830-november-2019-lisbon-portugal-pdf (Original work published 2020)

Chicago Citation

Bonacho, Ricardo, Maria José Pires, and Elsa Cristina Carona Sousa Lamy. (2020) 2020. Experiencing Food: Designing Sustainable and Social Practices. 1st ed. CRC Press. https://www.perlego.com/book/1712864/experiencing-food-designing-sustainable-and-social-practices-proceedings-of-the-2nd-international-conference-on-food-design-and-food-studies-efood-2019-2830-november-2019-lisbon-portugal-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Bonacho, R., Pires, M. J. and Lamy, E. C. C. S. (2020) Experiencing Food: Designing Sustainable and Social Practices. 1st edn. CRC Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1712864/experiencing-food-designing-sustainable-and-social-practices-proceedings-of-the-2nd-international-conference-on-food-design-and-food-studies-efood-2019-2830-november-2019-lisbon-portugal-pdf (Accessed: 14 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Bonacho, Ricardo, Maria José Pires, and Elsa Cristina Carona Sousa Lamy. Experiencing Food: Designing Sustainable and Social Practices. 1st ed. CRC Press, 2020. Web. 14 Oct. 2022.