1

Introduction

A sociologist goes to the movies

This is a book about movies and the ways in which they interpret and imagine human lives in the world today. It is written from a sociological perspective, which is unusual considering that sociology is a discipline committed to the analysis of social groups and the real people who populate those groups. Movies are social products created by the efforts of creative individuals working collaboratively across a number of professions, including writers, actors, advertisers, musicians, composers, sound and lighting technicians, editors, cinematographers, investors, and many others. The films themselves, however, are not people and so are not often the object of sociological interest. It would be mistaken, however, to interpret this disinterest as a rejection by sociologists of the importance of movies, or as a judgment on their centrality to the cultures of societies around the world. It is, instead, an oversight, a byproduct of the ways in which sociology initially developed and the important issues that captured the imagination of the founders of the discipline.

Sociology emerged in the second half of the nineteenth century, largely in response to the dramatic social changes in European and American societies wrought by industrialization, paramount among which was the increasing disjuncture between the lives of those in urban and rural areas and that between the poor and those more prosperous. Considering that movies only became available for viewing by the public in theaters in the mid-1890s (Streible, 2008: 45), their presence as a force within American culture only gradually came to be understood, largely due to their popularity among the growing populations of larger cities like New York and Chicago. Today, however, the significance and ubiquitous presence of popular culture – in its many forms – has become an important focus of critics, scholars, and educators throughout the world.

In this book, I look into the various ways in which Hollywood movies can be viewed and analyzed from a sociological viewpoint. Doing so allows for a more critical understanding of the movies while not diminishing one’s enjoyment of viewing them. Those in Hollywood make movies that they hope will earn substantial profits and thus secure their own positions within the industry. This movie industry produces entertainment in the form of films that provide enjoyment, escape, and perhaps even education for the audience. Besides producing entertaining moving pictures, however, many filmmakers strive to produce cinematic art while others may also intentionally or not produce a vehicle of propaganda or, less controversially, a type of socialization. What it means to say that movies “educate” can be read in a variety of ways. While one might acknowledge that a film set in the past, like Amadeus (1984), for example, or even more so the Spielberg film from 1997, Amistad, can be said at least potentially to educate those in the audience who had been unfamiliar with the topic, it is unlikely that audiences seek this form of informal education through the movies and also unlikely that films made at least partially with this intention in mind actually succeed in that aim. The film historian, David Thomson, would agree: “in history there is little evidence that the masses have gone to the movies to be educated, though there is every possibility that, blind to formal education, they are shaped by the light in the dark in ways they hardly appreciate” (2012: 77). From a sociological view, films can be said to educate in the sense that they effect a measure of informal socialization, teaching boys and girls – and men and women as well – how to perform the complexities of gender, among other things.

It is helpful to remember that what we view in the movie theater or elsewhere has been produced at a very high cost. Indeed, because movies are so expensive to make, advertise, and distribute, the producers are always mindful that profitability depends in part on the careful alignment of the movies’ stories with widespread cultural beliefs and values. Box office successes will rarely contradict or question those beliefs but, instead, invariably embrace them particularly in the films’ climactic scenes in which the audience learns the ending of the story and the answer to the question, “What was the movie about?” This is what we will refer to as the ideological theme of some films. By this I mean that movies provide pleasurable entertainment – which is their utopian element – but often also contain more realistic life lessons that reinforce widespread cultural beliefs and values. The utopian moment is most pronounced: the appeal of the films produced by the major Hollywood studios lies with their delivery of happy endings in which justice prevails, evil is punished, and deserving individuals are rewarded. Less noticed is the ideological element or theme.

E. Ann Kaplan (1983: 12–13) further explains that an ideology need not be any consciously held belief but more typically refers “to the myths that a society lives by, as if these myths referred to some natural, unproblematic ‘reality.’” Hollywood serves to buttress the prevailing ideological beliefs by concealing what is actually a problematic reality. According to Kaplan, the “dominant Hollywood style, realism (an apparent imitation of the social world we live in), hides the fact that a film is constructed, and perpetuates the illusion that spectators are being shown what is ‘natural.’” (1983: 13). In Lady and the Tramp, for example, Tramp – an adventurous dog who roams free living by his wits – is rejected by the genteel society of Lady’s friends and family until he demonstrates his value to the family by saving the family’s infant child from a voracious rat. He is welcomed into the family, receives his collar, and escapes the fate awaiting the interesting ensemble of dogs that Lady meets during her brief stay in the pound. Disney delivers both a happy ending and an ideological reinforcement of the widespread cultural belief that upward mobility is possible – at least for those who merit it. We can see that the “promesse du bonheur” claimed by the German writer, Theodor Adorno, to suffuse all art is also part of the pleasure experienced by audiences of even the most commercial of cinematic productions.

Since I will be examining the relationship between movies and the real world outside of the theater, it is important to consider for a moment the question, however hackneyed, of whether art imitates life or the reverse. As a sociologist, I am trained to answer that art would imitate life, since the source of art would necessarily come from experience. But as one who also admires great art and am often awed by the imaginations of those who produce it, I must acknowledge as well that life will often return the favor so to speak by imitating art in its many forms: high, low, and “middle-brow.” The film critic, Ann Hornaday (2017: 240), has written that “Public debates rage on regarding to what extent movies influence the audience – what we believe, what we value as a society. But one doesn’t have to buy into simplistic cause-and-effect arguments to acknowledge that, with its realism, aspirational glamour, and enormous reach, cinema has an outsized impact on social norms and assumptions.” I could not agree more. This effect of art on life has also been recognized by the film historian, David Thomson. In one of his recent books Thomson directs his attention to the effect that screen images have on those in the audience:

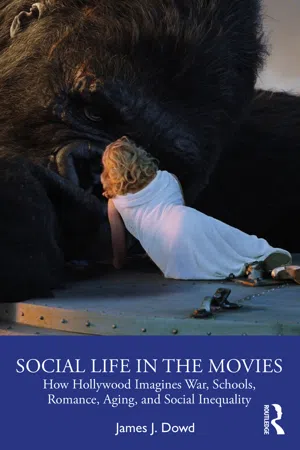

A distinctive feature of the sociological approach to film analysis is its methodological rigor in the choice of films. Rather than build an analysis around a single film, the chapters in this book systematically sample dozens of films (or even hundreds as in the case of romance films). The book includes several chapters that focus on popular film genres, such as war movies, romance films, school movies, and the three major King Kong films (from 1933, 1978, and 2005). Other chapters deal with social issues rather than exclusively on a particular genre. So, for example, there are chapters on gender inequality, alienation, and films that focus on older characters.

By writing this book, I hope among other things to reinforce the reader/viewer’s recognition of the socially conservative nature of much Hollywood movie production. Traditional gender roles still abound; older characters are rarely central to the stories told on the screen and when they do appear they are typically presented in stereotypical, often negative, ways; and, as another example, war movies are often romantic tales of heroic soldiers whose brave exploits are shown in the same frame juxtaposed with that most powerful American cultural image, the American flag. The romantic war film is only one of three major types of war movie but it is both the most frequently made and by far the most popular. The heroization of the American soldier through the manipulation of flag images encourages an acceptance of war as inevitable. Even those military deployments that are unnecessary, ill-advised, and unsuccessful are presented in ways that emphasize the courage and resourcefulness of American soldiers while ignoring the terrible costs of war (the 2001 film directed by Ridley Scott, Black Hawk Down, is one instance that I will examine in greater detail in the chapter on war movies).

There are many excellent books on film; what I do differently, however, will be evident in both the large, systematic sampling of films in almost every chapter in the book and in the various topics and genres covered therein. This sampling issue has been a troublesome element that has hampered previous attempts to develop a sociological analysis of film. Some recent books that analyze the nature of films that were made in the wake of the tragic events of September 11th, 2001, for example, focus on only a small selection of possible post 9/11 films and for that reason invariably raise the issue of why these films – but not other seemingly even more relevant films – were chosen. Even the most insightful analysis would suffer if the reader were to question the author’s choice of films. I strive to avoid this questionable methodology by including all or most films that meet the sampling criteria that I explicitly and carefully lay out. There can be no question here of choosing films that support the analysis but avoiding others that do not. I believe that this proposed book is far more successful in avoiding this problem and in advancing the development of a sociology of film.

So how might a sociologist approach the analysis of a popular Hollywood movie that might be different from, say, that of a film reviewer like Kenneth Turan or Manohla Dargis? One obvious difference is the number of films a sociologist is likely to include in her analysis. Occasionally a writer for a magazine like National Review or a newspaper like The New York Times will compare several films, such as when the critic might discuss the ways in which a particular director’s latest film differs from – or continues similar themes that were present in – earlier movies.1 But the nature of the film reviewer’s task is to describe the basic facts of a single film that opened recently in a local theater and to indicate what the reviewer believes to be its merits, flaws, and possible interest to the readers of the paper or magazine. For a sociologist, however, the point of the analysis is to trace the connections between the dominant cultural beliefs of the society and the ways in which films of a particular type reinforce or challenge those taken-for-granted beliefs. In order to do this, a single film is almost always insufficient. It is only when several or many films are analyzed that the film scholar can be confident that a pattern not only exists but is significant and is not merely a coincidental or trivial occurrence in the films under review.

The sociological approach to film analysis will also consider the ways in which the films under review constitute complex cultural objects. A cultural object can be any material or immaterial human construction that conveys meaning to those who share the local culture. A simple cultural object would be something like, say, a traffic signal which switches from green to amber and then to red in order to control the flow of traffic through an intersection. Drivers understand (one hopes) the meaning of the colors, knowing that to drive through a red light would not only risk an accident but would also subject the driver to a substantial fine. Red means stop! Green indicates that it is time to move. These meanings are persistent and singular in that they mean one thing and only one thing; this meaning remains the same today as tomorrow and the day after. In contrast, the meaning of a complex cultural object may vary over time and place. It may also be a source of conflict as its meaning may differ greatly across disparate social groups. These changes and differences derive from a group’s social experience and thus it is highly possible that different groups may see the same complex object differently. Political figures like Donald Trump, Hillary Clinton, or Barack Obama are clearly complex cultural objects in that our approval or disapproval of a particular politician is not only an individual response but one that is often shared within larger aggregates like, for example, a region of the country, or a social class, ethnic group, generation, and even gender. In the American South, the Confederate Battle Flag is clearly a complex object, the meaning of which differs considerably across different regional, class, and racial groups.

Following from this difference between simple and complex cultural objects are two general approaches to the sociological study of movies. The first selects films that may be seen as windows onto society while the second approach attempts to analyze movies as an unstable container of society’s unresolved social and cultural issues. Historical films, as well as those that are biographical or based on “true stories,” generally fall into the first category of movies that – like windows – we may peer through to glimpse the wider culture of everyday beliefs and practices. We approach films of this kind as realistic or reliable portraits of actual social life; movies are the work of an intelligent observer of the passing scene. Just as we read books to learn, so too we view films to learn about the people and world about us. A good literary example is the writing of Charles Dickens, from which we learn much about British society during the period of laissez-faire competitive capitalism. Another example would be the films by British “New Wave” directors in the 1950s and ’60s that focused on the working class in England. Films such as Lindsay Anderson’s (1963) This Sporting Life or Tony Richardson’s The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (1962) provide a realistic examination of the challenges facing proud young men in working-class Britain in the late 1950s. One could also point to the naturalist movement in American novels and paintings in the 1930s and ’40s, including such instances as Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath or Dreiser’s American Tragedy. Some Hollywood films of the past several decades that illustrate this “realistic” approach to social issues include Sully (2016), Spotlight (2015), Dunkirk (2017), Manchester by the Sea (2016), Marriage Story (2019), and many others.

There is a difference between literature and film in this regard. That is, although one might differ with, say, Charles Dickens about his understanding of the evils of industrialization, at least one knows who to argue with, i.e., Dickens’ novels are clearly his creations and, knowing more about Dickens allows one a better understanding of his novels. The same is not quite so clearcut with films. A Hollywood movie is not like a novel in that it is a collective and multi-staged effort. The content of a film is not so easily attributable to a particular individual and, even more important, the motive behind the making of a film is heavily commercial although artistic impulses are also present. Consequently, it is more difficult to approach movies as an open and clear window onto society, regardless of how seemingly realistic the movie may be.

Alternatively, we may also approach films not as windows onto culture but as complex cultural objects, that is, as an object in the physical or social world that possesses complex meaning. Film is a container of complex cultural meaning; it contains all of the forces, unresolved ambiguities, and values, rules, prescriptions, and proscriptions that may also be present in the wider culture itself. Examples of films of this type would include Guillermo del Toro’s 2017 film, The Shape of Water, or another film from 2017, War for the Planet of the Apes. Both of these films bring to the surface issues that lie embedded within our culture but which might be difficult to discuss objectively o...