![]()

1

Understanding Ethical Systems

![]()

Case Study

A Client in Need

You have been seeing a client for psychotherapy who had agreed to your standard fee. The client was experiencing severe distress due to an abusive marriage and had elected for individual therapy because her husband refused marital therapy. After attending four sessions, she missed the next two. You then receive a telephone call from her and she says that she and her husband have separated. She reluctantly tells you that her bank accounts have been frozen, she has no access to money, and has no family or friends to whom she can turn. If she doesn’t soon pay her rent she will be evicted from her apartment. She would like to continue in therapy, but can’t drive, and rather than paying for bus fare, has been buying food with what little cash she has.

Questions for consideration

1. What individuals and/or groups would you consider in arriving at a solution to this dilemma?

2. What considerations is each individual/group owed? Why?

3. What is your choice of action? Why?

4. What alternative choice(s) of action(s) did you consider? Why did you not choose them?

![]()

Our ethics serve to define us as professionals. To be recognized as a profession means that a group of practitioners has been granted a monopoly over the use of its knowledge base, the right to considerable autonomy in practice, and the privilege of regulating its members. Professional status is only bestowed on an occupation that makes a commitment to the public good, however (see Chapter 2). This social contract is enacted through a profession adopting and following a code of ethics.

In order to honour and sustain this interdependence, a professional code of ethics ought not contain anything that is discordant with the values of society at large. That is, the societal recognition of a profession does not signify that unique ethical principles apply to that occupation. Rather, it acknowledges the distinct expertise that members of the profession possess and the difficult situations that they are expected to deal with. A professional code of ethics should therefore represent the application of generally accepted ethical principles to activities characteristic of or idiosyncratic to the profession.

A code of ethics also should be based upon a coherent ethical system so that we might be able to put it to use. This system must be specific enough that we know what to do, while being general enough that we know how to be ethical in novel situations. And it must guide us to actions and outcomes acceptable to the society we serve. There is no system of ethics that manages to fulfill these functions perfectly. Each has its strengths and its weaknesses, and each has something to contribute to being an ethical psychologist. This is why an understanding of ethical systems is necessary for the professional psychologist.

There is another very important purpose for learning about ethical systems. Most of our actions are shaped by beliefs we have about the nature of the human condition. These beliefs serve as a filter by which we selectively attend to all of the potential information available to us as we try to understand the world around us and how best to live our lives (Koltko-Rivera, 2004; Unger, Draper, & Pendergrass, 1986) and they shape our personal moral system (Bendixen, Schraw, & Dunkle, 1998). Our actions can be incongruent with our personal moral beliefs, however, and when they are, the likelihood that we will behave immorally increases. Also, if our personal moral beliefs are too discrepant with those embodied within our professional code of ethics, we will find it extremely difficult to reliably meet our professional ethical responsibilities. Thus, an understanding of ethical systems can help you bring your professional behaviour into harmony with your personal morals and with the system of ethics of our profession so that you might be more consistently an ethical psychologist.

Four Foundational Ethical Systems

History’s greatest philosophers have been particularly concerned with what constitutes an ethical life. You have probably noticed that your moral sense has much in common with that of many other people and is at odds with that of some others. Similarly, philosophers have been debating which system of ethics is best for thousands of years. While there is no one completely uncontroversial ethical system, it is generally accepted that the most important attempts in Western philosophy to understand the nature of human ethics are represented by four foundational systems: teleology, deontology, virtue, and relational.

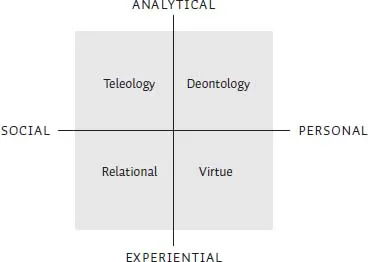

Each of these systems is based on a philosophical worldview that is valid and useful to a point, without quite managing to be complete. The allegorical tale of “the blind men and the elephant” probably describes this situation best, whereby each touched a part of the elephant and believed that he understood it entirely. The blind man who held the ear declared that an elephant is a fan, he who touched the belly that it is a wall, the trunk that it is a snake, the leg a pillar, and the tail a rope. Each had only a limited grasp of the whole and was thus only partially correct. We are all similarly blind in that no human being can comprehend the entirety of the human condition. Each philosophy describes only part of the whole. Fortunately for us, we are not expected to resolve this millennia-old problem. Instead, we can understand each system as a contribution to an unknowable whole. One way to conceptualize the relationship between the parts and the whole of ethics is presented in Figure 1.1.

The four foundational ethical systems can be usefully mapped along two dimensions: analytic versus experiential and social versus personal. An analytic approach to ethics favours rational analysis while an experiential approach privileges participation in real-world processes. Along the other dimension, a social approach honours publicly observable phenomenon whereas a personal approach values introspection. By organizing ethical systems in this way we can see some of the similarities and differences among them—and glimpse one possible way that they might form a whole.

Figure 1.1 Relationship between four ethical systems

TELEOLOGY

Teleology (from the Greek telos, meaning “end” and logia, meaning “reason”—therefore “reasoning from ends”) is an analytic and social approach to ethics. The teleological system operates from the perspective that right actions are those that produce desired outcomes. Teleology is described as consequentialistic in that it is concerned with the consequences of our actions. There are a number of different variants of teleology, with by far the most established being utilitarianism as articulated by Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832) and John Stuart Mill (1806–1873). Its basic premise is: an act is right if, all other things being equal, it produces or is likely to produce the greatest amount of good for the greatest number of people. What constitutes a “good” outcome is typically either the happiness or preferences of the persons involved or affected. A pure utilitarian approach for psychologists would require that our code of ethics contain only one principle: consider the utility of each possible outcome for each action appropriate to each situation we face.

A more practical variant of utilitarianism is rule utilitarianism, which can be stated as: we should behave in accordance with rules that, all other things being equal, produce or are likely to produce the greatest amount of good for the greatest number of people in most circumstances. Such a system has the advantage of allowing a profession to codify rules of ethics, and each professional then only has to know which rule to apply to a given situation.

DEONTOLOGY

Deontology (from the Greek deont, meaning “duty” and logia, meaning “reason”—therefore “reasoning from duty”) was first articulated by the classical Greek philosopher Plato (429–347 BCE) and honed to a fine edge by Immanuel Kant (1724–1804). Deontological ethics is an analytic and personal approach that urges us to reflect inward when solving a particular ethical dilemma in order to establish obligatory principles to guide future ethical reasoning. The deontological system calls upon us to act as if the rationale that underlies our action were to become a universal duty. It is therefore often referred to as duty ethics. From a deontological point of view, neither the intention to bring about good results nor the actual consequences of an act are relevant to assessing ethical worth. Deontology posits that the rightness of an action depends upon whether we perform it in accordance with, and out of respect for, absolute and universal ethical principles. These principles, because of their universal nature, create obligations. From a deontological point of view, neither the intention to bring about good results, nor the actual consequences of an act, are relevant to assessing ethical worth. For example, suppose a psychologist decided to prolong services beyond their usefulness in order to keep receiving payment from a client. The rationale embodied in such an act is, “it is acceptable to gain money at another’s expense,” and the duty would be something like, “advance your own interests.” Because no one would consent to being so treated, the deontological argument goes, no rational being would accept such a duty as universally obligating. The obligatory principles that are considered to apply to the profession of psychology are: respect for autonomy; nonmaleficence (doing no harm); beneficence (helping others); fidelity (honesty and integrity); and justice (fairness and equitableness).

VIRTUE

Virtue ethics has it roots in the work of another great ancient Greek philosopher, Aristotle (384–322 BCE) and was the dominant approach in Western ethics until the eighteenth century when reason came to be honoured over authority (especially religious authority, which had incorporated Aristotelian principles). Interest arose again in the late 1950s, fueled by a growing dissatisfaction with deontology and teleology as neglecting the subjective experience of the person who is striving to be ethical. Virtue ethics place the character of the individual in the central role of ethical considerations. Virtue ethics focus on the ideal rather than the obligatory and on the intentions of the actor rather than the consequences of actions. The rightness of an action does not depend upon its consequences nor its correspondence with principles, but rather depends upon its having the right motive. What is considered ethical is unique to the individual and cannot be completely explained by logic. Where teleology and deontology address what is ethical, virtue deals with who is ethical. When considering the ethics of a situation, therefore, virtue thus encourages us to ask: How will my actions embody the type of person I want to be? Thus, it is not the act that is appraised, but the character of the person who acts. Virtue ethics orients professionals to think ethically at all times rather than only when confronted with an ethical dilemma. Virtue ethics call upon us to aspire to develop traits of character that will naturally result in meeting our ethical expectations. As such, ethical rules and principles are not seen as unimportant, merely insufficient.

RELATIONAL

Relational ethics focus on our experience of others in the social world. Founded in the feminist thought of Carol Gilligan (1936–) and Nel Noddings (1929–) and developed by Vangie Bergum (1939–) and John Dossetor (1925–), relational ethics highlights how relationships are innate and fundamental to the human condition. Based on the premise that ethical actions always take place in relation to at least one other person, relational ethics requires us to ask: How will my actions manifest consideration of and my concern for others? Ethical knowledge, reasoning, and action are understood as being imbedded within a complex, never completely predictable, relational context (Bergum & Dossetor, 2005). Behaving ethically is thus not a personal, analytic exercise—it is experiential and social. That is, being ethical entails action in real relationship with real consequences. As such, relational ethics is concerned with how we treat each other rather than the why of a particular ethical decision. What is considered ethical is thereby also open to change and reconsideration as the context of our actions change in response to new relationships and events. This highlights how ethical actions are reciprocal in that professional and client both act and react. Misplaced trust, unfairness in gains and losses, and a whole suite of human relational issues inevitably emerge. These can cause strains in the relational ties that bind people together socially, and relational ethicists point out that we must be willing to continually negotiate new and revised relationships as we seek to be ethical.

ETHICAL SYSTEMS APPRAISED

The major strength of teleology—that it provides us with a calculative framework that allows ethical decisions to be implemented in a logical, objective fashion—is also its fundamental weakness. By focusing on the greatest amount of good for the greatest number of people, teleology allows for the sacrifice of the individual in the name of the common good. Such an “ends justifying the means” approach tends to stand against the basic value that Canadian society places on the innate worth of the individual. It was also the rationale given by most of those who were tried for war crimes associated with cruel medical experimentation perpetrated by the Nazis during the Second World War (see Chapter 11). The greatest practical difficulty associated with teleology is that it leaves unanswered the question of what counts as a “good” outcome. Some argue that what is good is hedonistic or pleasurable. Others argue that what is good is what is ideal such as honesty, justice, or beneficence, while others argue that it is some mixture of these.

The inherent difficulties with a deontological approach to ethics come from two sources. First, similar to the problem with teleology, there is no consensus as to which ethical principles are universal and absolute. Second, situations arise whereby principles are at odds with one another. So one might argue that the principle of beneficence requires that we lie to persons dying of an incurable disease in order that they maintain their hope in the future, while another would argue that the principle of autonomy requires that we not withhold information that they might use to make decisions about how to live what remains of their lives. The most pressing practical difficulty arising from deontology is that, with its emphasis on the analytic application of duties without reference to the consequences, it tends to encourage students in professional programs to make ethical judgements primarily in reference to the laws of society, rather than being based on principles grounded in social contracts. This tendency is also associated with a dec...