![]()

![]()

1

Traditional Knowledge, Healing, and Wellness

An Introduction

LESLIE MAIN JOHNSON

Examining health and well-being in a holistic way leads to looking at the role of Traditional Knowledge in daily practices that promote health and well-being. These practices integrate Traditional Knowledge of food and nutrition, including obtaining and preparing traditional foods, use of plant- and animal-based medicines for maintaining personal and family health, and approaches to “right living” and spiritual balance based on cultural knowledge and traditions. A strong sense of identity and knowledge of traditional skills also contribute to a sense of well-being. These practices in the home and among kin and community networks promote health and well-being. I have termed these generally known culturally based approaches to well-being “vernacular healing.” Where illness or injury are more severe, they may require the intervention of specialist healers, who have special skills and gifts, and are experts in healing. These two approaches to promoting well-being and health are complementary. In this volume, we explore ways to promote individual and community well-being and healing in northern communities, ranging from daily practices for well-being, lessons from the land, and spiritual pathways to healing and wellness.

Northern environments offer many challenges, including marked seasonality, shifting resources, and fluctuations in productivity of key plants, game animals, and fisheries. Nonetheless, Indigenous populations of northern North America have persisted and thrived, despite these challenges. Weather patterns and climatic fluctuations have also affected northern regions, requiring resilient adaptation. The people dwelling in the North found the means to good and healthy lives, with high-quality local foods and few diseases. Despite the challenges offered by seasonality and periods with low availability of plant foods, people had healthy and balanced diets. Times of game shortage and extreme weather events did occur, but people persisted, crafting flexible and innovative solutions to the challenges they faced. Now these northern regions are part of the nation-states of Canada and the United States, and the present century has seen a range of accelerating changes that affect human and environmental health in the North.

Contemporary northern communities, primarily Indigenous, are impacted by many multifaceted and interrelated factors that work to diminish community viability and well-being. Impacts of development on key resources affect food sovereignty and access to cultural foods (Baker and Fort McKay Berry Group, this volume; Taylor 2014; Moore et al. 2015), which are foundations of health (Kuhnlein and Receveur 2007; Kuhnlein, Receveur, and Chan 2001; Kuhnlein et al. 2006; Nakano et al. 2005). Contaminants, landscape degradation, and other correlates of development continue to create new environmental problems and challenges for northern communities, affecting food security and traditional livelihoods (e.g., Bertia et al. 1998; Kuhnlein et al. 2009; Kuhnlein 2014; Lambden, Receveur, and Kuhnlein 2007; Poirer and Brooke 2000; Baker and Fort McKay Berry Group, this volume). Both spiritual and physical health can be impacted by contaminants and effects on significant game species that form a foundation of traditional nutrition (e.g., Samson and Pretty 2006). Contamination of medicines and berries is also of concern (Baker 2015; Baker and Fort McKay Berry Group, this volume). Climatic change further destabilizes a system already under stress, adding urgency to finding effective solutions (Savo et al. 2016). Indigenous perspectives thus foreground a focus on northern environmental health and how it impacts community well-being in these regions (e.g., Baker 2015; Deline First Nation 2005; Parlee 2015; Parlee, O’Neil, and Lutsel K’e Dene First Nation 2007; Dokis-Jansen 2015; Poirer and Brooke 2000; Usher and Inuit Tapirisat of Canada 1995).

Seeking to understand sources of individual and community resilience, and how these may shape programs and interventions is also important (Walker et al. 2006; see also Bolton 2012). In particular, there is a high degree of agreement among Indigenous Elders, Knowledge Keepers, and those who create programs and strategies for healing and promotion of well-being that being on the land, language, and meaningful connection of youth with Elders are important (e.g., Morgan 2013, 2014; Health Canada 2013). There is widespread agreement among Indigenous Northerners that on-the-land activities are needed for effective healing from trauma, promotion of well-being through reconnection to tradition, and learning of identity. For example, the National Aboriginal Youth Suicide Prevention Strategy report lists “dislocation from land” as one of the risk factors for youth suicide. According to this report, one of the factors that promotes resilience is “activities for youth that increase their connection to community, the land, each other, Elders, their family, and that promote cultural continuity” (Health Canada 2013, 10). Similarly, Richard Oster et al. (2014) found that cultural continuity and language maintenance appeared to foster lower morbidity with type 2 diabetes in a meta-analysis of diabetes prevalence in Prairie First Nations communities; their work did not assess land-based activities or access to traditional foods directly.

Explicit statements that detail the importance of land for well-being are relatively rare. In a significant article in the International Indigenous Policy Journal, Julian Robbins and Jonathan Dewar (2011) do make the connections between healing and land explicit. They write, “traditional knowledge and Indigenous spirituality hinges on the maintenance and renewal of relationships to the land. Indigenous land bases and the environment as a whole remain vitally important to the practice of traditional healing” (n.p.). Richard Bolton details the importance of engaging in traditional harvesting practices on the “land” for promotion of health and well-being in his 2012 thesis. In the abstract, he writes, “It presents both material and non-material benefits of contemporary IIFN [Iskatewizaagegan No. 39 First Nation] fishing practices. Results indicate that IIFN members actively partake in fishing activities and continue to rely on fish as an essential part of their diet. Fishing practices also provide avenues for IIFN to convey cultural knowledge, strengthen social cohesion and help articulate a sense of Iskatewizaagegan identity. As such, they are integral to the community’s physical and psychological health as well as Iskatewizaagegan culture and spirituality” (i). Although references to these connections in the literature are relatively rare, a range of Indigenous wellness promotion reports (e.g., Morgan 2014; Citizens of the Kaska Nation and the Town of Watson Lake 2008; FNHA 2014) and papers from the ethnobiology literature on traditional foodways and the like (e.g., Kuhnlein and Receveur 2007) implicitly make the point that land and well-being are linked. Moreover, Indigenous writers (e.g., Atleo 2004; Deloria 1973; Kawagley 1995; Van Camp 2002) strongly present these connections.

Even where the importance of connecting language with land and youth with Elders are explicitly recognized as essential to community and individual health, economic factors may pose significant barriers. Anecdotal reports suggest that programs are often limited by inadequate funding to take people out on the land. Transportation costs are significant in the era of centralized localized residence in hamlets or reserve communities and fixed work and school schedules. Requirements for cash to subsidize motorized transportation and to supplement inadequate incomes also stress scarce financial resources for these programs.

Key sources that detail other studies of northern Traditional Knowledge, plant medicines, and healing include Alestine Andre (2006) and Andre and Allen Fehr (2001), who describe Gwich’in plant uses and plant medicines; and Robert Bandringa and Inuvialuit Elders (2010), who have produced a lovely illustrated compendium of Inuvialuit Elders’ knowledge of plants and plant uses. An evocative consideration of the impact of Port Radium on the land and on human health by Great Bear Lake, Northwest Territories, is found in Deline First Nation’s Bek’éots’erazhá Nįdé /If Only We Had Known: The History of Port Radium as Told by the Sahtúot’įnę (2005). A rich early source on traditional plants for food and medicine, including oral histories was compiled by Anore Jones (1983) for the Maniilaq Association in western Alaska. Priscilla Russell Kari (1987) produced a lovely little book on Dena’ina plant names and uses, which was subsequently published with colour illustrations in conjunction with the National Park Service. Another Alaska source of relevance is the guide to use of traditional Alaska foods for cancer survivors published by the Alaska Tribal Health Consortium (Alaska Native People et al. 2008). The Vuntut Gwitchin of Old Crow, Yukon, together with Erin Sherry, produced a rich volume detailing plants and landscapes of the Dempster Highway corridor with many Elders’ narratives in 1999 (Yukon Gwitchin). In a more academic vein, Yadav Uprety and colleagues (2012) published a review of use of boreal forest plant medicines in Canada, while Courtney Flint et al. (2011) describe how berries can aid in health promotion in Alaska. Craig Gerlach and Phillipe Loring (2013) examine the importance of sustainable traditional food systems for community well-being in the North. My own work details aspects of plant uses for food and healing among the Witsuwit’en, an Athapaskan-speaking group in north central British Columbia (Johnson Gottesfeld 1995) and medicinal plant uses and concepts of healing as well as food plants and ethnoecology among the Gitxsan (Johnson 1997, 2006; Johnson et al. 2006) in northwestern British Columbia. Together, these works suggest the significance of Traditional-Knowledge-based well-being for a number of Indigenous communities in Alaska and the Canadian North, and underscore the need to explore effective ways to implement this knowledge to promote community wellness.

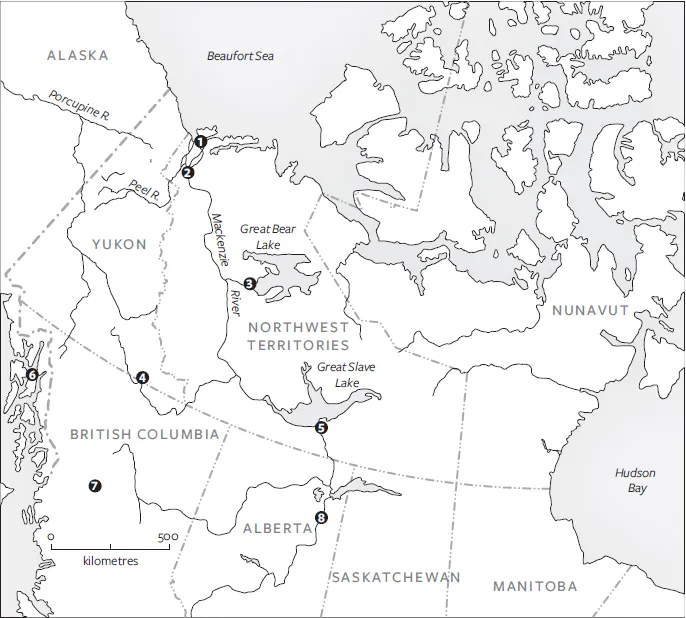

We focus here on the role of Traditional Knowledge for promotion of well-being in northern communities. Our particular region of concern comprises the northwest region of North America: Alaska, the Yukon, the western Northwest Territories, Northern British Columbia, and Northern Alberta (Figure 1.1). The main concern of this volume is the interrelated web of traditions, culture, communities, and well-being. We deal with healing and health, which are in themselves holistic and in the round.

This collection’s key concepts are used in many contexts to reflect the richness and complexity of the world itself. We also use words to describe wellness and illness, health and disease, and balance and imbalance in English and the Indigenous languages of the communities. We use words in the language of the academy, doctors, healers, and people in the communities.

Traditional Knowledge has many facets, comprising Traditional Knowledge of plants and animals for food; plants and animals for medicine; traditional skills for making what is needed and what is beautiful; Traditional Knowledge of the land itself (commonly referred to as Traditional Ecological Knowledge); knowledge of who one is; and knowledge of right and appropriate ways of walking and being in the world (e.g., Ignace, Turner, and Peacock 2016; Legat 2012; Turner 2005; Turner, Ignace, and Ignace 2000). The concept of tradition is also multifaceted. Tradition can include what we have learned from our parents, grandparents, and other personal mentors; what they bring forward from the past; and the reservoir of cultural stories and knowledge that have carried on since time immemorial. Tradition can also come from the observations and innovations of individuals who are working toward new approaches and solutions that are rooted in who they are and the cultural traditions from which they come (Reo 2011). Traditional Knowledge is conceptually linked to wisdom, often phrased as the wisdom of the Elders.

FIGURE 1.1 Index map of locations of cases described in this volume: 1 Mackenzie Delta-Kittigazuit; 2 Mackenzie Delta Inuvialuit and Gwich’in communities; 3 Deline; 4 Watson Lake; 5 Fort Resolution; 6 Kake, Alaska; 7 Gitxsan and Gitanyow; 8 Fort McKay

We are also looking at concepts of health and of well-being. These concepts, too, are complex. Health is not the simple absence of clinical illness. Health is a positive state of wellness. Writer Wendell Berry, in a 2015 book called Our Only World, suggests that the word health itself implies wholeness. Health includes the mind, body, and spirit, which are integrated in each person, and extends to the communities in which we live. Health includes what we do, what we eat, and what we believe. Well-being takes a step further and asks, how can we live well? How can we dwell in wellness? Both of these concepts require embodiment and practice. Health is something that you do, rather than have. Well-being carries on from the individual to the family and community, and beyond. Well-being and health connect to concepts of relationship: they include the relations of people to each other and to the other beings who dwell on Mother Earth, and to the land itself. Indigenous cultures and communities are rooted in traditions and self-knowledge, and they are emplaced—connected to their traditional lands.

Indigenous concepts of wellness are very broad and holistic (see Adelson 2000), encompassing knowledge of traditional laws, identity and social relationships, sovereignty and self-determination, traditional foods, ecological relationships, and relationships to the land, respect and freedom from violence, as well as specific treatments of illness conditions more similar to medical notions of disease or injury (Morgan 2013, 2014). Intergenerational transmission of knowledge is also required for promotion of community sustainability and well-being (see Legat 2012). This transmission is affected both by reduced opportunities for experiential and land-based learning and by language loss (see Johnson a...