![]()

1

QUAKING

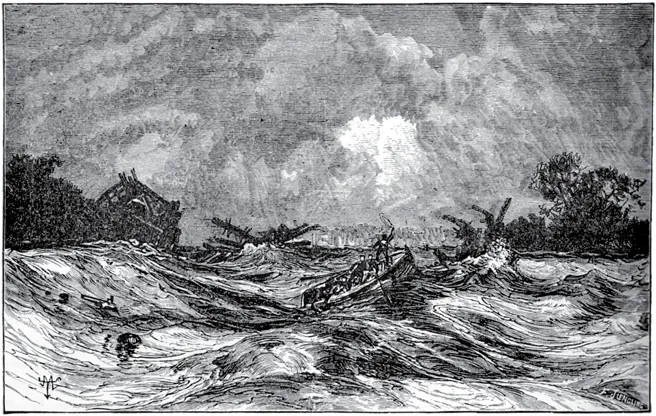

Dawn revealed that Mississippi River navigation manuals were useless. Islands were missing, submerged logs rose to the water’s surface to block channels, and riverbanks had disintegrated. The New Orleans, one of the first steamboats ever to ply the river, was north of New Madrid during the first shock. Like many Euro Americans west of the Appalachians awakened by the shaking, the crew first supposed that the din was an Indian attack. As the boat passed through New Madrid, crowds from the bank begged to be taken aboard. People and houses already had been swallowed, and those seeking refuge hoped it would be safer to ride out the shocks while traveling downstream. “Painful as it was, there was no choice but to turn a deaf ear to the cries of the terrified inhabitants of the doomed town,” related the voyage’s chronicler. Even when the shaking subsided, trees and broken chunks of islands scratched at the boat’s hull, making it difficult to sleep onboard. What was supposed to be a crowning achievement of technological innovation, a celebration of a new era in the integration of markets and people in the growing nation, instead turned into a solemn passage full of “anxiety and terror.”1

Others corroborated the astonishing riverside sights and sounds. Despite his crew’s desire to flee the boat and climb to land, Scottish naturalist John Bradbury decided to ride out the earthquakes in open water. He calmed each crew member with liquor and continued down the river. The next morning, Bradbury captured the sights and sounds of disorder during an aftershock. “The trees on both sides of the river were most violently agitated, and the banks in several places fell in, within our view carrying with them innumerable trees, the crash of which falling into the river, mixed with the terrible sound attending the shock, and the screaming of geese and other wild fowl, produced an idea that all nature was in a state of dissolution,” he wrote. A French boat pilot offered another description of the terrifying sound, which “was in the ground, sometimes muffled and groaning; sometimes it cracked and crashed, not like thunder, but as though a great sheet of ice had broken.” Passing through a village south of New Madrid, a another boat pilot surveyed the morose scene of a Catholic graveyard partially sunken into the river with a split wooden cross marking exposed graves. “All nature appeared in ruins, and seemed to mourn in solitude over her melancholy fate,” he wrote to his aunt in Pennsylvania.”2

One recurring element of popular lore about the earthquakes was true: the Mississippi River temporarily flowed backward. The shaking combined with major cracks in the riverbed to disrupt the river’s flow, creating massive upstream waves. The French pilot described an immense swell traveling north: “So great a wave came up the river that I never seen one like it at sea. It carried us back north, up-stream, for more than a mile, and the water spread out upon the banks, even covering maybe three or four miles inland. It was the current going backward. Then this wave stopped and slowly the river went right again.” A different pilot reported being carried upstream for ten to twelve miles. In St. Louis, the river did not reverse course, but the water churned and bubbled like it was boiling.3

Another long-held piece of trivia about the earthquakes—that they rang church bells in Boston—is less likely. The shaking tolled mistimed bells, awaking the inhabitants of St. Louis, central Ohio, and locations as far away as Charleston, South Carolina. While people in mid-Atlantic states felt faint tremors, they were not strong enough to ring bells in Boston. In a recent study that has downgraded the estimated severity of the three major temblors of 1811 and 1812, seismologists at the U.S. Geological Survey have suggested that the apocryphal report from Boston stems from people who mistook an account from Charleston, South Carolina, for a report of events in Charlestown, Boston’s oldest neighborhood.4

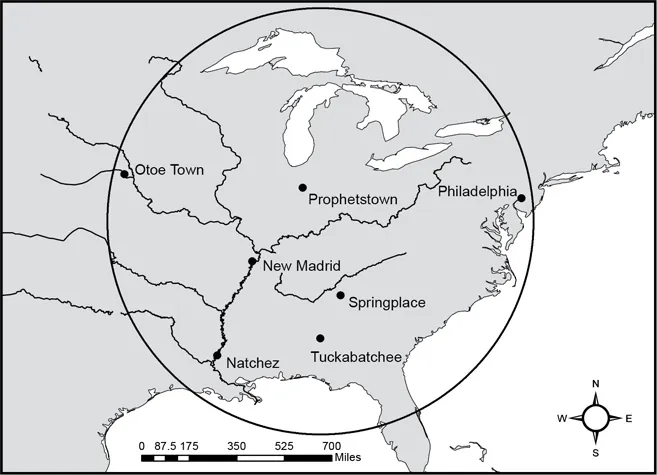

The earthquakes were nonetheless alarming and unprecedented for people across eastern North America. In small lakes northwest of Detroit, turbulent waters led turtles to surface and reveal themselves as easy food. Weak shaking in New Orleans and Baltimore marked the earthquakes’ outer boundaries along the Atlantic coast and the Gulf South. And though maps that reconstruct the tremors’ severity in the West often stop at St. Louis, betraying a bias for accounts from the United States, people well west of the Mississippi River felt the shaking. In Osage territory, ice cracked at the Arkansas River’s edge, and in what is today Nebraska, Otoes and Euro American traders had a lively discussion about the reason for the disturbance.5

Map 1. Approximate geographical scope of earthquakes with selected sites. (Map by Jasmine Zandi.)

Disorientation and nausea were abiding physical reactions to the quaking. “It seemed as if my bedstand was on a rough sea, and the waves were rolling under it, so sensible were the undulations,” wrote a preacher in Kentucky. Another settler in Kentucky claimed to “reel about like a drunken man.” From northwest Tennessee, a correspondent with a naturalist in New York reflected on the earthquakes’ effect on “both the body and the mind of human beings.” If people “had been deprived of their usual sleep, through fear of being engulfed in the earth, their stomachs were troubled with nausea and sometimes even with vomiting. Others complained of debility, tremor, and pain in the knees and legs,” he related. An eerie array of sounds and smells complemented rifts in the ground, sandblows, and toppled chimneys. “The awful darkness of the atmosphere which, as formerly, was saturated with sulphurous vapor, and the violence of the tempestuous thundering noise that accompanied it … formed a scene, the description of which would require the most sublimely fanciful imagination,” wrote a woman in New Madrid.6

At the time of first earthquakes, New Madrid was a bustling and diverse site of trade and transportation. The town that came to bear the earthquakes’ name resulted from the Spanish Empire’s encouraging settlers to establish a regional buffer in the Missouri Bootheel between Osage and British territory. After the French ceded Louisiana following the Seven Years’ War, the Spanish began awarding land grants to willing settlers in 1763. Aided by Delaware and Shawnee trade networks, Euro American traders established posts for selling furs and other goods. Beginning in the 1790s, eastern Indian and U.S. migrants complemented their efforts by cutting timber, hunting game, and piloting boats down the Mississippi River. By 1808, there were about one hundred houses in New Madrid and twenty-four cabins in nearby Little Prairie.7

In those communities closest to the epicenters, a difficult choice accompanied the destruction: remain in houses in various states of collapsing, sinking, burning down, and floating away, or ride out the shocks in open air, where trees were regularly falling and the ground was “opening in dark, yawning chasms, or fissures, and belching forth muddy water, large lumps of blue clay, coal, and sand.” These chasms made fleeing to higher ground especially treacherous. But the estimated 2,000 residents of New Madrid and its vicinity had no other option, as the town sunk twelve feet by one estimate, and gushing water submerged the newly sunken land. Fleeing to a hill thirty miles north became a wading expedition through four or five miles of hot, knee-deep water. Others who remained in shattered settlements benefited from boat wrecks on the Mississippi River. Provisions washed ashore, and pilots who did manage to hold on to their cargo sold it at reduced prices rather than risk losing it all in another tremor. “This accident to the boats was the salvation of the homeless villages,” wrote a nineteenth-century chronicler of Missouri.8

The earthquakes left indelible marks on the land and reshaped settlement patterns west of the Mississippi River. A woman fleeing the Missouri Bootheel for Kentucky reported that the earthquake had “sunk, Bursted, and destroyed a great part of that Country.” From Cincinnati, a settler wrote back to his brother in Massachusetts about the twin effects of earthquake damage and the threat of violence with Indians. After describing half-mile-long cracks in the ground out of which water and sand spouted, he noted, “People are moving out of this country faster than they ever moved into it.” Large holes where sand blew out of the ground are still present in Missouri and Arkansas farmlands today. Other changes in the land were more dramatic. The seismic activity created Reelfoot Lake in western Tennessee, a shallow body of water with partially submerged tree roots that now makes for good recreational fishing. South of the epicenter, on a tributary of the Mississippi River, a family discovered that their nearby well and smokehouse were located on the opposite side of the river after the first earthquake rerouted the tributary. The St. Francis River basin in present-day Arkansas devolved into swampland, prompting late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Cherokee migrants there to relocate west. Nearby, the earth swallowed up a mill and destroyed a ten-acre apple orchard. Two decades later, a travel writer captured the demise of the St. Francis River, its “clear waters … obstructed, the ancient channel destroyed, and the river spread over a vast tract of swamp.”9

Figure 2. Scene of the Great Earthquake in the West. A nineteenth-century woodcut depicts a tumultuous scene on the Mississippi River during one of the major earthquakes in 1811–1812. (From Devens, Our First Century, 220; Filson Historical Society, Louisville, Ky.)

Those who fled broken and flooded farmland and river trading posts did not soon return, and neither did future settlers replace them. More than a decade after the shaking subsided, a passerby found New Madrid in a “wretched & decayed” state. Matters had not improved by 1839, when another traveler called the town “dilapidated” and exaggerated that there was “but one comfortable residence in the place.” Only trappers found the new landscapes promising, as the fallen trees and new cracks in the terrain created prime habitat for fur-bearing creatures. Future western migrants largely passed over the damaged region where current-day Tennessee, Arkansas, and Missouri meet.10

Despite these hazards, there were remarkably few casualties. Only a handful of firsthand narratives mention individuals who disappeared in the desperate hours following the major temblors. The largest number of lost people recorded in a single account was a group of seven Native Americans. According to a single survivor quoted in a widely reprinted newspaper report, they fell into a chasm. In a region with low population densities in the 1810s, deaths were more likely in the dozens than in the hundreds or thousands. While these earthquakes were every bit as powerful as those that devastated Lisbon, Lima, and Caracas in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, their epicenters’ considerable distance from large urban areas limited their death toll.11

The earthquakes’ scope facilitates a continental historical lens. Across eastern North America, people struggled to explain the tremors and their larger significance for human order in the early nineteenth century. From Indian councils and church meetings to congressional halls and plantation desks, people situated the earthquakes alongside other human and environmental anomalies in 1811 and 1812. Claiming direct revelation from increasingly proximate divine forces, charismatic leaders articulated new visions of order that challenged established political authorities in the United States and in Native American polities. But these figures were not the only people who intertwined issues of land, spirit, and politics to find the tremors portentous. Mounting signs of disorder and imbalance captivated and concerned everyone.

“I hope these things are not ominous of national calamity,” wrote Congressman Abijah Bigelow to his wife, Allison. The Federalist legislator from Massachusetts had just listened to a sermon in which a Washington City preacher “spoke of the Richmond fire and intimated that the comet, the indian battle, the shock of Earthquakes were warnings to the nation, that the almighty had even caused the alarm bells to be rung, alluding to the earth quake in several places causing the bells to ring.” Former First Lady Abigail Adams shared her alarm with her son John Quincy. “The Natural World is in a turmoil as well as the political,” she wrote. Across territorial and epistemological boundaries, people interpreted the earthquakes in light of human and environmental anomalies that began in 1811 and carried over into 1812.12

Flooding during the spring of 1811 initiated what one 1830s chronicler called the “Annus Mirabilis of the West.” Latin for “year of miracles,” the term “Annus Mirabilis” came from England in 1666, when the Great Fire of London, a bubonic plague, the English defeat of the Dutch navy, and Isaac Newton’s discoveries, along with the year’s demonic numerals, made English people speculate about the events’ collective significance. The U.S. Annus Mirabilis continued inauspiciously enough with an odd sight: squirrels “seen pressing forward by tens of thousands in a deep and sober phalanx to the South.” Not the last time in 1811 that animals would strangely march in unison, many squirrels also drowned in the Ohio River. A summer heat wave and stagnating pools of water spread disease and yielded a “pestilential vapour” along the Mississippi River. Then a September hurricane hit Charleston, and inland tornados capped off a series of alarming, though not altogether unusual, weather patterns.13

When the Great Comet of 1811 appeared in skies that fall, the Annus Mirabilis began in earnest. Paired with a solar eclipse in September, the comet was among the most widely visible in recorded history. Across the world, people gazed at its two-pronged tail with wonder, curiosity, and confusion. Journals became lively forums for study and debate. A contributor to Baltimore’s Weekly Register captured the range of responses to the comet: “A thousand conjectures are formed as to its immediate object and ultimate effects. … Sinners tremble at the dreaded termination of their career, while the philosopher calmly prepares to search into the hidden secret.” Mathematical calculations stood comfortably beside esoteric ruminations on the mysteriousness of God’s “Infinite Mind” and more focused devotional statements on human depravity and sin. These ranging discussions demonstrated the fusion and porousness of Enlightenment rationalism and Christian enthusiasm in Euro American world views in the early nineteenth century. In this intellectual climate, commentators were more likely to disagree about the immediacy of divine influence and the limitations of human reason than to question the existence of a divine role in nature. But given the literal distance between the comet and its observers, debates about divine intentionality and the connections among spiritual, environmental, and human orders were less pressing than they became when the earth began shaking.14

The comet’s disappearance coincided with the first temblor on December 16, 1812, leading some observers to suspect that these curiosities were directly related. In Kentucky and Ohio, people discussed the possibility that the comet had struck the earth, causing it to quake. The Louisiana Gazette and Daily Advertiser of New Orleans supposed that the point of impact was in the California mountains, while people aboard that steamboat thought it landed in the Ohio River.15

Whether or not they made direct connections between the comet and the earthquakes, people remained preoccupied with the sky. Accounts of strange sights and abnormal atmospheric conditions filled letters and newspapers. Numerous observers expected earthquakes during “lowering weather,” a nineteenth-century term for low atmospheric pressure. Those familiar with the nascent study of electricity suspected links between winter thunderstorms and the shaking, and published studies contained countless measurements of thermometer and barometer readings, wind direction, and the extent of cloud cover. Other conditions could not be quantified. A correspondent with naturalist and American Philosophical Society officer Benjamin Smith Barton struggled to explain the sky’s appearance during his trip from Frankfort to Bardstown, Kentucky, during the first temblor. During the foggy and cloudy night, “a meterous exhalation or electricity or something else illuminated our road,” he wrote. “It resembled a dim moon-shine, or (if I may use an excentric comparison) it appeared as if a hoghead of moonshine had been emptied upon us & diffused itself equally throughout the surrounding gloom.” North Carolina’s skies were alight with other oddities. An army captain reported to a preacher the sight of “three extraordinary fires,” which were “as large as a house on fire,” streaking across the sky in different directions. The preacher himself saw a meteor accompanied by a “whitish substance, resembling a duck in size and shape” that tailed off in a cloud of smoke.16

Like the marching squirrels earlier that year, animals behaved strangely before and during the earthquakes. Famed naturalist John James Audubon was riding his horse in Kentucky when, moments before the shaking, his mount slowed and braced itself. Nearly all firsthand accounts of the tremors mentioned the howling and screeching of animals that accompanied the creaking of houses, trees, and rocks. One couple that spent the evening “watching for the Coming of Death” found that at dawn, there “were great bears, panthers, wolves, foxes etc. side by side with a number of wild deer, with their red tongues hanging out of their mouths.” That afternoon brought ...