- 396 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

User Experience Re-Mastered: Your Guide to Getting the Right Design provides an understanding of key design and development processes aimed at enhancing the user experience of websites and web applications. The book is organized into four parts. Part 1 deals with the concept of usability, covering user needs analysis and card sorting—a tool for shaping information architecture in websites and software applications. Part 2 focuses on idea generation processes, including brainstorming; sketching; persona development; and the use of prototypes to validate and extract assumptions and requirements that exist among the product team. Part 3 presents core design principles and guidelines for website creation, along with tips and examples on how to apply these principles and guidelines. Part 4 on evaluation and analysis discusses the roles, procedures, and documents needed for an evaluation session; guidelines for planning and conducting a usability test; the analysis and interpretation of data from evaluation sessions; and user interface inspection using heuristic evaluation and other inspection methods.

- A guided, hands-on tour through the process of creating the ultimate user experience – from testing, to prototyping, to design, to evaluation

- Provides tried and tested material from best sellers in Morgan Kaufmann's Series in Interactive Technologies, including leaders in the field such as Bill Buxton and Jakob Nielsen

- Features never before seen material from Chauncey Wilson's forthcoming, and highly anticipated Handbook for User Centered Design

Information

CHAPTER 1. What Is Usability?

Jakob Nielsen

EDITOR'S COMMENTS

Jakob Nielsen has been a leading figure in the usability field since the 1980s and this chapter from his classic book, Usability Engineering (Nielsen, 1993), highlights the multidimensional nature of usability. To be usable, a product or service must consider, at a minimum, these five basic dimensions:

■ Learnability

■ Efficiency

■ Memorability

■ Error tolerance and prevention

■ Satisfaction

An important point made by Nielsen and other usability experts is that the importance of these dimensions will differ depending on the particular context and target users. For something like a bank automated teller machine (ATM) or information kiosk in a museum, learnability might be the major focus of usability practitioners. For complex systems such as jet planes, railway systems, and nuclear power plants, the critical dimensions might be error tolerance and error prevention, followed by memorability and efficiency. If you can't remember the proper code to use when an alarm goes off in a nuclear power plant, a catastrophic event affecting many people over several generations might occur.

In the years since this chapter was published, the phrase “user experience” has emerged as the successor to “usability.” User experience practitioners consider additional dimensions such as aesthetics, pleasure, and consistency with moral values, as important for the success of many products and services. These user experience dimensions, while important, still depend on a solid usability foundation. You can design an attractive product that is consistent with your moral values, but sales of that attractive product may suffer if it is hard to learn, not very efficient, and error prone.

Jakob's chapter describes what is needed to establish a solid foundation for usability – a timeless topic. You can read essays by Jakob on topics related to many aspects of usability and user experience at http://www.useit.com.

Back when computer vendors first started viewing users as more than an inconvenience, the term of choice was “user friendly” systems. This term is not really appropriate, however, for several reasons. First, it is unnecessarily anthropomorphic – users don't need machines to be friendly to them, they just need machines that will not stand in their way when they try to get their work done. Second, it implies that users' needs can be described along a single dimension by systems that are more or less friendly. In reality, different users have different needs, and a system that is “friendly” to one may feel very tedious to another.

Because of these problems with the term user friendly, user interface professionals have tended to use other terms in recent years. The field itself is known under names like computer–human interaction (CHI), human–computer interaction (HCI), which is preferred by some who like “putting the human first” even if only done symbolically, user-centered design (UCD), man-machine interface (MMI), human-machine interface (HMI), operator-machine interface (OMI), user interface design (UID), human factors (HF), and ergonomics, 1 etc.

1.Human factors (HF) and ergonomics have a broader scope than just HCI. In fact, many usability methods apply equally well to the design of other complex systems and even to simple ones that are not simple enough.

I tend to use the term usability to denote the considerations that can be addressed by the methods covered in this book. As shown in the following section, there are also broader issues to consider within the overall framework of traditional “user friendliness.”

Usability and Other Considerations

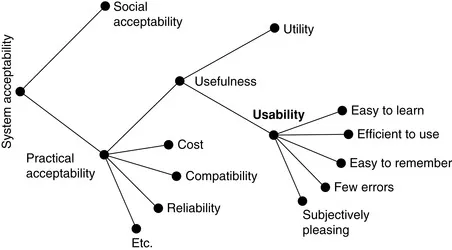

To some extent, usability is a narrow concern compared with the larger issue of system acceptability, which basically is the question of whether the system is good enough to satisfy all the needs and requirements of the users and other potential stakeholders, such as the users' clients and managers. The overall acceptability of a computer system is again a combination of its social acceptability and its practical acceptability. As an example of social acceptability, consider a system to investigate whether people applying for unemployment benefits are currently gainfully employed and thus have submitted fraudulent applications. The system might do this by asking applicants a number of questions and searching their answers for inconsistencies or profiles that are often indicative of cheaters. Some people may consider such a fraud-preventing system highly socially desirable, but others may find it offensive to subject applicants to this kind of quizzing and socially undesirable to delay benefits for people fitting certain profiles. Notice that people in the latter category may not find the system acceptable even if it got high scores on practical acceptability in terms of identifying many cheaters and were easy to use for the applicants.

EDITOR'S NOTE

SOCIAL NETWORKING AND SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY

In the years since the publication of this chapter, social networking and other collaboration technologies, such as Facebook, Twitter, and blogs, have become popular with millions of users. These new technologies have great promise for bringing people together but also pose new issues around social acceptability. Take Twitter as an example. Messages about conditions at work or how bad one's managers are might be considered socially acceptable whining by the originator, but the person's managers might view the same whining on Twitter as detrimental to the company. Comments on social networking sites can persist for years and a single photo or comment could harm someone's chances for a new job or affect revenue for a company. Human resource personnel can Google much personal information when they screen candidates, but is that socially acceptable? Social networking can be a boon or a disaster for individuals and organizations.

Given that a system is socially acceptable, we can further analyze its practical acceptability within various categories, including traditional categories such as cost, support, reliability, compatibility with existing systems, as well as the category of usefulness. Usefulness is the issue of whether the system can be used to achieve some desired goal. It can again be broken down into the two categories, utility and usability (Grudin, 1992), where utility is the question of whether the functionality of the system in principle can do what is needed and usability is the question of how well users can use that functionality. Note that the concept of “utility” does not necessarily have to be restricted to the domain of hard work. Educational software (courseware) has high utility if students learn from using it, and an entertainment product has high utility if it is fun to use. Figure 1.1 shows the simple model of system acceptability outlined here. It is clear from the figure that system acceptability has many components and that usability must trade-off against many other considerations in a development project.

|

| FIGURE 1.1. |

| A model of the attributes of system acceptability. |

Usability applies to all aspects of a system with which a human might interact, including installation and maintenance procedures. It is very rare to find a computer feature that truly has no user interface components. Even a facility to transfer data between two computers will normally include an interface to trouble-shoot the link when something goes wrong (Mulligan, Altom, & Simkin, 1991). As another example, I recently established two electronic mail addresses for a committee I was managing. The two addresses were ic93-papers-administrator and ic93-papers-committee (for e-mail to my assistant and to the entire membership, respectively). It turned out that several people sent e-mail to the wrong address, not realizing where their mail would go. My mistake was twofold: first in not realizing that even a pair of e-mail addresses constituted a user interface of sorts and second in breaking the well-known usability principle of avoiding easily confused names. A user who was taking a quick look at the “To:” field of an e-mail message might be excused for thinking that the message was going to one address even though it was in fact going to the other.

Definition of Usability

It is important to realize that usability is not a single, one-dimensional property of a user interface. Usability has multiple components and is traditionally associated with these five usability attributes:

■ Learnability: The system should be easy to learn so that the user can rapidly start getting some work done with the system.

■ Efficiency: The system should be efficient to use so that once the user has learned the system, a high level of productivity is possible.

■ Memorability: The system should be easy to remember so that the casual user is able to return to the system after some period of not having used it without having to learn everything all over again.

■ Errors: The system should have a low error rate so that users make few errors during the use of the system, and so that if they do make errors they can easily recover from them. Further, catastrophic errors must not occur.

■ Satisfaction: The system should be pleasant to use so that users are subjectively satisfied when using it; they like it.

Each of these usability attributes will be discussed further in the following sections. Only by defining the abstract concept of “usability” in terms of these more precise and measurable components can we arrive at an engineering discipline where usability is not just argued about but is systematically approached, improved, and evaluated (possibly measured). Even if you do not intend to run formal measurement studies of the usability attributes of your system, it is an illuminating exercise to consider how its usability could be made measurable. Clarifying the measurable aspects of usability is much better than aiming at a warm, fuzzy feeling of “user friendliness” (Shackel, 1991).

Usability is typically measured by having a number of test users (selected to be as representative as possible of the intended users) use the system to perform a prespecified set of tasks, though it can also be measured by having real users in the field perform whatever tasks they are doing anyway. In either case, an important point is that usability is measured relative to certain users and certain tasks. It could well be the case that the same system would be measured as having different usability characteristics if used by different users for different tasks. For example, a user wishing to write a letter may prefer a different word processor than a user wishing to maintain several hundred thousands of pages of technical documentation. Usability measurement, therefore, starts with the definition of a representative set of test tasks, relative to which the different usability attributes can be measured.

To determine a system's overall usability on the basis of a set of usability measures, one normally takes the mean value of each of the attributes that have been measured and checks whether these means are better than some previously specified minimum. Because users are known to be very different, it is probably better to consider the entire distribution of usability measures and not just the mean value. For example, a criterion for subjective satisfaction might be that the mean value should be at least 4 on a 1–5 scale; that at least 50 percent of the users should have given the system the top rating, 5; and that no more ...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Contributors

- CHAPTER 1. What Is Usability?

- CHAPTER 2. User Needs Analysis

- CHAPTER 3. Card Sorting

- CHAPTER 4. Brainstorming

- CHAPTER 5. Sketching

- CHAPTER 6. Persona Conception and Gestation

- CHAPTER 7. Verify Prototype Assumptions and Requirements

- CHAPTER 8. Designing for the Web

- CHAPTER 9. Final Preparations for the Evaluation

- CHAPTER 10. Usability Tests

- CHAPTER 11. Analysis and Interpretation of User Observation Evaluation Data

- CHAPTER 12. Inspections of the User Interface

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access User Experience Re-Mastered by Chauncey Wilson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Computer Science & Human-Computer Interaction. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.