![]()

Part One

Vernacular Influences

![]()

1

Folk Surrealism

Marci Kwon

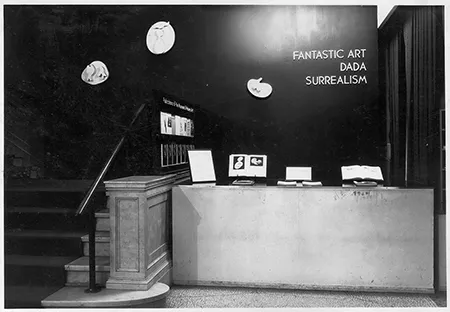

On December 9, 1936, the Museum of Modern Art opened Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism (hereafter FADS, Figure 1.1). The second in a series of exhibitions organized by Alfred Barr to highlight prominent trends in twentieth-century art, FADS included 711 works, including painting, sculpture, drawings, prints from the fifteenth to twentieth centuries, advertisements, scientific instruments, architecture, film, animation cells, folk art, and the work of children and the so-called insane.1 FADS’s catholic array epitomizes the eclectic nature of MoMA’s early exhibition program, a phenomenon that has drawn renewed scholarly attention in the past decade.2 Building on this work, my essay examines the early history of MoMA through the lens of what I describe as the demotic imperative of the 1930s.3 From this vantage, the inclusion of popular, commercial, and folk art in MoMA’s galleries was neither pandering commercialism nor uncritical nationalism, but rather the museum’s attempt to address—and thus conjure into being—the unified mass known in period parlance as the “people,” without forfeiting its commitment to vanguard art.4

Figure 1.1 Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art / Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY.

MoMA’s attempts to negotiate these ostensibly opposed aims engendered an ethos of amateurism I describe as “folk surrealism,” in reference to two prominent strands of the museum’s early curatorial program.5 Surrealism’s valorization of nonprofessional modes of cultural production allowed the museum to frame folk art and the work of children as innate forms of expression, thereby demonstrating the broad accessibility of Surrealist principles. Put differently, MoMA’s ethos of amateurism can be described as a kind of domestic primitivism, which, like all primitivizing formulations, relies on the “outsider” position of its objects to prove the universality of its concept. This stance proved untenable, endangering the museum’s status as a bastion of sacralized culture and appearing uncomfortably close to the strategies of totalitarianism by the late 1930s. MoMA’s attempts to expand the idea of who counts as an artist and what counts as art thus touched upon the paradox inherent to attempts to level established cultural hierarchies, which, taken to their logical extreme, threaten to destroy the boundaries between art and the world around it.

MoMA and the Common Man

In an oft-cited irony, MoMA opened just days after the Stock Market Crash of 1929. The museum’s first three years of operation coincided with the nadir of the Great Depression, before the implementation of the New Deal in 1933. This turmoil created an imperative for artists and poets to respond directly to the present moment, pithily described by Wallace Stevens as “the pressure of reality.”6 MoMA’s founding charter appeared to answer this “pressure of reality,” by describing popular education as one of its central goals.7 Despite this, the museum’s three wealthy founders, and especially Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, led many to view MoMA as a symbol of the elitist culture that gave rise to the Great Depression. As New Dealer Edward Bruce sneered in 1933, MoMA was considered by many to be “the little snob which was recently dedicated by the Rockefellers who have put their dead hand on everything they touch.”8 By virtue of its immutable identity as an art museum and connection to the Rockefellers, MoMA thus found itself at odds with the decade’s emergent collectivist tenor. Although it was established in 1931, the Whitney never had to face this problem as intensely as MoMA because of its identity as an American art museum, as well as Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney’s deep ties to the Greenwich Village artistic community.9

In other words, the paradox facing artists during the 1930s was an ingrained part of MoMA’s early institutional identity: while its stated charge was to promote modern art, the museum’s relevance depended on its ability to make these aims accessible to a public. Curator Alfred Barr was uniquely positioned to address this situation. Although he had completed postgraduate work with Paul Sachs at Harvard, Barr’s scholarly approach was equally indebted to Princeton medievalist Charles Rufus Morey’s anthropological investigation of art and culture as seen in The Index of Christian Art.10 Following Morey’s capacious attitude toward culture, Barr organized exhibitions that extended beyond the museum’s traditional charge of fine arts, which he understood as a gesture toward popular legibility. As Barr later explained to critic Dwight MacDonald, “We hope that showing the best in the arts and popular entertainment and of commercial and industrial design will mitigate the arcane and difficult atmosphere of painting and sculpture.”11

Yet it was curator Holger Cahill who was responsible for MoMA’s earliest attempt to directly answer the demotic imperative of the 1930s. Cahill, who took over as MoMA’s director while Barr was on sabbatical in 1932, remains best known for his directorship of the Federal Arts Project (FAP) of the Works Progress Administration (WPA). Cahill was also an accomplished curator, initiating his tenure at MoMA with an exhibition whose title announced its populist ambition: American Folk Art: Art of the Common Man, 1750–1900.12 For Cahill, folk art offered a means of reconciling modernism’s “revolution in form” and the decade’s radical politics.13 Unlike MoMA’s Harvard-educated moderns, Cahill’s interest in folk art originated in his early experience with Greenwich Village anarchism. None other than ardent leftist Michael Gold praised Cahill’s proletarian pedigree: “He hoboed and dug ditches and sweated in the Kansas harvest fields, he had washed dishes, rebelling at his own worthlessness, and swaggered in the fire zone and at political rallies with a newspaper reporter’s badge.”14

In Art of the Common Man’s catalogue essay, Cahill proposed that folk art’s simplified forms, so reminiscent of modernist abstraction, originated in preindustrial human instinct. Folk art, he wrote, was “an expression of the common people and not an expression of a small cultured class,” forming a lineage of modernism rooted in amateurism rather than industrial production.15 This approach was indebted to Marxist scholar Thorstein Veblen, whom Cahill studied with at the New School of Social Research.16 Drawing on Veblen’s 1918 book The Instinct of Workmanship, which traced the transition from handmade craft to mechanized production, Cahill positioned folk art as the last bastion of “workmanship” in an era of industrialized labor. Keeping with this logic, Cahill limited the exhibition to itinerant painting, wooden and metal sculpture, and plaster ornaments, deliberately excluding furniture, silver, glass, and other examples of decorative arts he deemed the work of “professionals.”17

Yet even within this idealistic framing, Cahill did not entirely eschew established cultural hierarchies.18 As he stated at the end of his catalogue essay, “Folk art cannot be valued as highly as the work of our greatest painters and sculptors, but it is certainly tied to a place in the history of American art.”19 Cahill’s deliberate privileging of fine art underscores folk art’s implicit challenge to the history of art museums in the United States, which since the Gilded Age had been charged with displaying “unique aesthetic and spiritual properties that rendered it inviolate, exclusive, and eternal.”20 Folk art’s presence in the museum instead located modern art’s most cherished principles of formal simplicity in the work of amateurs.21 Art of the Common Man thus placed MoMA in a precarious situation: while demonstrating the “inviolate, exclusive, and eternal” qualities of modern art, folk art’s connotations of amateurism also threatened to destabilize the very hierarchies that traditional museums were charged with upholding.

The untenability of this position became apparent with MoMA’s 1934 Westchester Folk Art. Hoping to boost museum membership, the museum organized a condensed reprise of Art of the Common Man at the Westchester Workshop, a community center specializing in arts education.22 In a gallery adjacent to the main exhibition, MoMA installed a show of children’s art from public and private institutions around Westchester County. The work was selected by teachers and judged by a committee including art critic Helen Appleton, artist William Zorach, and Barr himself, which awarded small monetary prizes to eleven of the nearly 400 entries.23 The exhibition illuminates the paradox inherent to MoMA’s ethos of amateurism. On the one hand, exhibiting the work of children alongside folk art demonstrated the broad purchase of modern art; on the other, the inescapable constraints of space and money required the committee to devise other standards of quality.

These competing imperatives of quality and expansiveness were also apparent during New Horizons of American Art, which closed three months before FADS. New Horizons included 435 examples of work produced under the auspices of the FAP, now headed by Cahill, who also organized the exhibition. In the foreword to the exhibition catalogue, Barr explicitly addressed notions of quality within the sprawling display, noting that Cahill selected each work “for its artistic value alone.”24 New Horizons also included a selection of children’s art made under the FAP’s education program, including works such as Passover Feast by the ten-year-old F. Rick (Figure 1.2). At Barr’s request, the museum acquired several examples of children’s work from the exhibition, compensating the child artists with opening invitations, free admission to the museum, film screenings, and lectures, ten complimentary museum tickets, and access to the museum library.25 Barr later echoed Cahill’s rhetoric about folk art when he noted that the best children’s art was “truer to the human type than the mature world of more precise and self-conscious knowledge.”26 Yet like Cahill’s qualification in the Art of the Common Man catalogue, the conditions of the museum’s acquisition also illustrate the liminal status of children’s art. While deserving of inclusion in the museum’s collection, they were procured by trade rather than purchase. Barr’s exacting connoisseurship in acquiring select examples from the exhibition furthermore suggests that his aesthetic judgment occurred within aesthetic categories rather than between them. In other words, Barr saw the “best” child’s drawing as worthier of consideration than a third-rate modernist work.

Figure 1.2 Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art / Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY.

Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism

For Barr, Surrealism’s emphasis on found objects and automatic drawing offered a model for narrowing the distance between amateur and p...