![]()

Night of the Living Dead

Midnight Mass

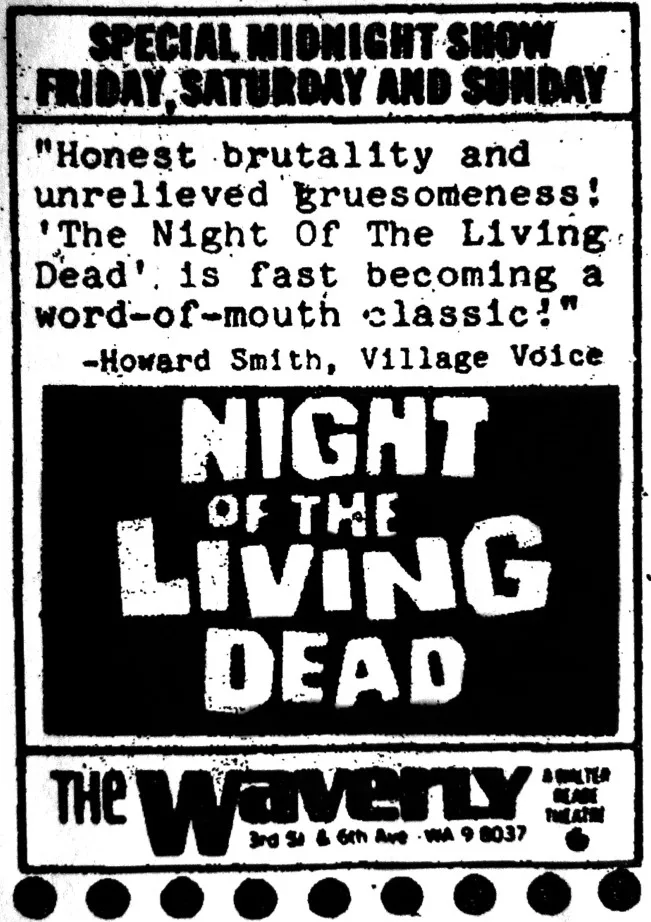

It’s a few minutes to midnight, any weekend in the summer of 1971. New York’s Waverly Cinema is packed, and Night of the Living Dead is about to begin. Some chatter nervously: it’s their first time watching a film that has been called the most terrifying ever made. But many of those waiting have seen Night many times, and know half the lines by heart: it has shown every Friday, Saturday and Sunday, only at midnight, since May. Night played at the Waverly for twenty-five weeks, then, after long, overlapping midnight runs at two other Manhattan cinemas, it returned, for fifty-five. The Waverly wasn’t quite the first place to revive Night at midnight, but it was home, the perfect spot for the cult to take root. The hippie musical Hair, then still in its first Broadway run, name-checked it as a bohemian meeting place.1 It was just round the corner from Washington Square, at the heart of Greenwich Village: then still a hub of the protest folk music scene, of gay liberation, avantgarde literature, the anti-war movement and the counterculture generally. The Waverly was three blocks from New York University. It was fifteen minutes’ stroll from the site of Timothy Leary’s LSD (League of Spiritual Discovery) Center, and barely ten from the Weather Underground safe house where three militant radicals blew themselves up in 1970, preparing to bomb a US Army dance. Greenwich Village was world-famous, synonymous with hip, intellectual, politicised youth.

The Waverly set the tone as Night’s midnight revival spread across America and Europe, and ran and ran through the 1970s. That the audiences were mostly young goes almost without saying: a 1968 MPAA survey found that viewers between sixteen and twenty-four accounted for half of the American box office, and far more for shocking, family-unfriendly films like Night. But the midnight movie phenomenon celebrated youth and rebellion: it was about staying up past bedtime, roaming the streets while regular citizens slept, and, usually, about defying good taste. Some films had been marginalised or vilified by the mainstream media. Those that played longest were often prized for transgressions and abnormality, like Freaks (1932) and Pink Flamingos (1972) (whose cannibal feast pays tribute to Night), or for anti-Establishment politics, like the anti-war freak-out King of Hearts (1966).

Night popularised midnight screenings but didn’t start them. In the 1950s, midnight horror movies had been popular at Halloween; and through the 1960s, art houses occasionally showed underground films by the likes of Andy Warhol and Kenneth Anger after the regular programming. But the first feature to enjoy an extended, midnight-only run was Jodorowsky’s lurid symbolist Western El Topo (1970), which opened at the Elgin, in New York’s Chelsea, on 1 January 1971. The idea of the midnight ‘cult’ took shape with El Topo: the ‘bearded and be-jeaned set’ came ritually, week after week, memorising the lines and bringing new ‘initiates’. The Village Voice called it ‘Midnight Mass at the Elgin’; the fans were ‘Jodorowsky’s witnesses’. The cult grew by word-of-mouth: advertising was limited to a small box in the Voice (the Waverly did the same for Night). Drugs were used. The repeated viewings were all about ‘getting’ El Topo, interpreting its metaphors. Long conversations in cafés afterwards were part of the experience.

Night lacks El Topo’s metaphysical pretensions and overtly psychedelic visuals, but it was a surprisingly logical follow-up. It combined earlier midnight movie traditions and audiences: a horror movie that was also seen as an art film. Like El Topo, Night was a genre piece that bent its genre out of shape; both films were gory, broke taboos. Both, despite fantasy elements, felt shockingly ‘real’, ‘totally convincing’: El Topo’s freakish actors were actually deformed; the underground press relished Jodorowsky’s claim that he ‘really raped’ a girl for one scene. Both films were made outside Hollywood and the ‘system’. And, like El Topo, Night was perceived to demand analysis, to work beneath the surface. Word had spread that it was an important, meaningful film, an urgent coded message on the state of America.2

I want to recapture Night’s significance for those early audiences: the ones who discovered it in the late 1960s, and the ones who made it a weekly ritual through the 1970s.

The Image Ten

Making an artistic statement was the last thing on the minds of George Romero and John Russo when they sat brooding in Samreny’s Restaurant, Pittsburgh, in January 1967. They and a few friends had struggled for years to get into the movies, and had already dabbled in unconventional film-making. In 1960, they shot an experimental portmanteau comedy, Expostulations, but ran out of money in post-production; more recently, they had failed to launch Whine of the Fawn, a Bergman-esque drama about medieval religious conflicts. Romero had tried longest and hardest: he shot his first films at fourteen, and spent the summer before college, 1957, assisting on Hollywood sets. Since 1963, he, Russo and some friends had operated their own Pittsburgh-based advertising company, Latent Image, and were gradually getting known for leftfield, low-budget innovation. But Latent Image was always intended as a bridge to features. So over provolone sandwiches they resolved to make one for $6,000, with ten investors kicking in $600 apiece. This time they’d play it safe with an exploitation picture. Their unpretentious working title: Monster Flick.

Assembling the rest of the ‘Image Ten’ was easy, and all provided services too. Four were Romero and Russo’s partners at Latent Image, including Russ Streiner, who produced, and Vince Survinski, production director. Karl Hardman and Marilyn Eastman worked in advertising elsewhere, and handled Night’s music and sound.

After several false starts, Romero showed up with half a story inspired by I Am Legend (1954), Richard Matheson’s novel about the last human in a world of vampires. Romero preferred to show the beginning of the undead’s takeover. The novel had already been filmed in Italy as The Last Man on Earth (1964), starring Vincent Price, and prefigured key details of Night: slow-moving hordes, hands grasping through boarded windows, an infected child on her deathbed, mounds of burning corpses – plus the protagonist dies. Last Man deserves more recognition, but lacks the qualities that made Night a hit: its rawness, brutality and grinding naturalism; its assault on taboos and cherished values; its queasy black humour and its topicality.

Six thousand dollars was not nearly enough, and the Image Ten eventually found additional investors. But they economised resourcefully. After months spent scouring Pittsburgh’s environs, they rented an Evans City farmhouse: it was due to be bulldozed, so they could do as much damage as they wanted. (As it happened, the boarded-up farmhouse stood for years to come, crowded with dummy ghouls and corpses, fodder for local kids’ nightmares.) They lived there during the shoot, partly to guard the equipment. There was no running water, so they bathed in the creek and carried buckets from the spring. They slept on army surplus cots; after Romero’s tore, he used the floor. But they usually only managed a few hours’ sleep anyway: they filmed around their day-jobs, on weekends, holidays and by night.

Undead hordes, boarded windows: The Last Man on Earth (1964)

Eight of the Image Ten appeared in the film, some in major roles: Streiner played Johnny, Hardman and Eastman were the Coopers. The remaining cast were mainly friends, colleagues, clients and local volunteers. Only Judith O’Dea (Barbara3) and Duane Jones (Ben) were even part-time professional actors, and neither had done a feature. The special effects were strictly DIY, with clay for rotting flesh and ping-pong ball eyes; the blood was Bosco chocolate syrup. (Romero worried that it would show up brown when Night was colourised for video.) The film-makers were so set on wringing ‘production value’ from anything to hand that they wrote in Barbara’s car crash because Streiner’s mother had dented her car shopping. This determination extended to dangerous stunts: Russo set himself on fire for the Molotov cocktail scene. The same recklessness energised post-production: Streiner got their final mix and sound-lock for free by beating the lab boss at a double-or-nothing chess game.

Night was shot mostly in sequence, which helps to explain why its intensity and bleakness build throughout – and perhaps why its subtexts emerge more in later scenes. The story continued to form during shooting: Romero only half-scripted it before they started. Russo helped write the remainder, and others threw in ideas. The same applied on set: everyone helped with make-up, lighting, set-dressing. At this distance, it’s impossible to disentangle who did what or had which idea, so I will speak of ‘the Image Ten’ or ‘the film-makers’ when a decision wasn’t clearly Romero’s. Indeed, Romero wasn’t even chosen to direct until pre-production was well under way. Nonetheless, Night is his film more than anyone else’s, and he ended up doing more than most ‘auteurs’. Besides conceiving the story, co-scripting and directing, he handled all of the camerawork and editing, acted (briefly), designed make-up and lighting effects and had final say on music and sound.

He took his time. The Image Ten’s situation was highly unusual: they made Night without a deadline and owned their equipment.

Ordinary effects: note the tub of Bosco chocolate syrup

Everyo...