- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

City Lights

About this book

In 1967, Charlie Chaplin told, 'I think I like 'City Lights' the best of all my films.' Based on archival research of Chaplin's production records, this work offers a history of the film's production and reception, as well as an examination of the film itself, with special attention to the sources of the final scene's emotional power.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 The Ending

Let's start at the end. The final shots of Charles Chaplin's City Lights (1931) constitute one of the most famous, memorable, and emotionally intricate endings of any movie in film history. In it Chaplin's iconic tramp character has just been released from prison, falsely accused of stealing money from a millionaire.1 He has given that money to the blind flower girl (Virginia Cherrill), with whom he has fallen in love, to pay for an operation. Returning that love, she also believes the tramp to be a wealthy benefactor. While he has been in prison, the flower girl has had surgery and, her sight restored, has opened a prosperous florist shop, hoping that her beloved will return to her. When the bedraggled Charlie happens by her shop, he spies her through the store window, first looks puzzled and surprised, then smiles. She's amused at this tramp's reaction, yet comes to the door to offer him a flower and a coin as he shuffles away, afraid that she might recognise him, might see him as he really is. As he reaches a hand back to her into which she places the coin, she identifies the pitiable tramp as her benefactor. The framing tightens as shots of both characters respond to this shock of recognition. The last shot of the film, the tramp's response to the flower girl's acknowledgment that now she can see, is reproduced on the cover of this book.

The tramp, as downtrodden as he has ever been, looks despondent after a newspaper boy shoots peas at him in the final scene of City Lights

This ending has entranced countless viewers around the globe since the film was released. It has also generated extensive commentary, perhaps none as memorable as James Agee's reflections in his 1950 essay, 'Comedy's Greatest Era':

At the end of City Lights the blind girl who has regained her sight, thanks to the tramp, sees him for the first time. She has imagined and anticipated him as princely, to say the least; and it has never seriously occurred to him that he is inadequate. She recognizes who he must be by his shy, confident, shining joy as he comes silently toward her. And he recognizes himself, for the first time, through the terrible changes in her face. The camera just exchanges a few quiet close-ups of the emotions which shift and intensify in each face. It is enough to shrivel the heart to see, and it is the greatest piece of acting and the highest moment in movies.2

Although Agee is, I believe, wrong in one detail - the flower girl first recognises the tramp not through her sight but through touch, by grasping his familiar hand - he's dead on target when he says that this ending 'shrivels the heart'.

Chaplin himself knew that this was a special moment in a special film. Discussing the final shot in a 1967 interview with Richard Meryman, Chaplin recalled,

I had had several takes and they were all overdone, overacted, overfelt. This time I was looking more at her. . . . It was the beautiful sensation of not acting, of standing outside of myself. The key was exactly right - slightly embarrassed, delighted about meeting her again - apologetic without getting emotional about it. He was watching and wondering what she was thinking and wondering without any effort. It's one of the purest inserts - I call them inserts, close-ups - that I've ever done. One of the purest.3

By the end of his career, Chaplin prized City Lights, In 1973, Peter Bogdanovich asked Chaplin, 'Which film of yours is your favorite? Can I ask you that? Or do you have no favorites?' Chaplin's reply: 'Oh, yes. I have. I like City Lights.'4

Examining the favourite film of one of the cinema's greatest figures may be reason enough to write about it. But there are other reasons, too. Commentators have long written about the protracted and difficult production of City Lights. As we shall see, a series of personal crises, industry shifts, and socio-cultural challenges combined to make this project a crucial one for Chaplin: the film-maker himself noted that shooting took such a long time because he kept wanting to make the film perfect. Furthermore, because Chaplin's surprisingly extensive production records are now available for scholars to examine at the Cineteca di Bologna, it is possible to trace with much more precision the production history of City Lights.

City Lights was a key transitional film for Chaplin - personally, aesthetically, and culturally. It was transitional because of the personal crises he endured just before and during the making of the film - his divorce from his second wife, Lita Grey, his separation from his sons of that marriage, Sydney and Charles Jr, and the death of his mother Hannah. It was transitional because of the aesthetic challenge of the film industry's shift to talkies, which took place while he was making City Lights: a master of pantomimic silent film comedy, Chaplin had to decide how he would respond to the challenge of the recorded soundtrack. It was transitional, finally, because he made City Lights while American culture itself was coping with the stock market crash, the end of the prosperity of the 1920s, and the beginnings of the downward economic spiral that resulted in the Great Depression.

Chaplin responded to these challenges with City Lights, and this book will look closely at the film, focusing on three concerns. I will first trace the production history of the film, as fully as is possible in a brief monograph, within the context of Chaplin's career. Second, I will look closely at the film itself, probing how elements of narrative and cinematic style intertwine to communicate the film's key themes and to evoke its powerful and complex range of emotions, culminating in a detailed examination of the final scene that may help us appreciate more fully Chaplin's achievements. Finally, and more briefly, I will examine how audiences and commentators, in the original release and subsequently, have responded to Chaplin's 'Comedy Romance in Pantomime', closing with an assessment of the film's key place in Chaplin's filmmaking career.

2 Chaplin's Hollywood Roots

City Lights was indisputably a Charlie Chaplin film, made with a degree of creative control unusual in Hollywood, before or since. As the writer, director, star, composer, and producer of City Lights, Chaplin had collaborators, to be sure, but he could make films without interference from above to a degree that even noted directors like Vidor or Ford or Hawks or Capra could only dream of.

Chaplin's history in Hollywood explains how this came about. A successful London music-hall comedian, Chaplin twice toured North America with a British music-hall troupe, appearing in vaudeville theatres, where he drew the attention of people in the burgeoning movie industry. In December 1913 he began working for Mack Sennett at Keystone Studios. In his year at Keystone he is known to have appeared in thirty-five short comedies (plus the longer Tillie's Punctured Romance, 1914), assembled his now-famous tramp costume, began directing his films, earned $150/week, twice his music-hall salary, and increased this after three months to $175/week).5

By December 1914, the end of his year at Keystone, the tramp films were already popular, and companies were beginning to bid for Chaplin's services. His second contract with Essanay paid Chaplin $1,250 a week; there he made fourteen comedies in 1915 and 1916, and the nation experienced a case of what one commentator called 'Chaplinitis'.6 The Mutual Film Corporation won his services in February 1916 by offering him $10,000 a week plus a $150,000 signing bonus to make twelve two-reelers. No small potatoes: according to a Consumer Price Index inflation calculator, Chaplin's $10,000/week salary in 1916 is equivalent to around $187,000 per week in 2006. His total pay from Mutual, bonus plus weekly salary ($670,000), would translate to over $12,500,000 in 2006 dollars.7

Through the years 1914-17, Chaplin was working for film companies that paid him for his services and owned the films he directed and in which he appeared. But Chaplin's shrewd path toward independence took a new turn when he signed a contract in June 1917 with the First National Exhibitors' Circuit. First National was a newly formed entity composed of a group of theatre owners who wished to buy films that they would, in turn, exhibit. Chaplin agreed to make eight films for First National: he received a $75,000 signing bonus and $125,000 for each two-reel film he made to cover his salary and production costs. First National paid for the prints and advertising; they also received 30 per cent of the total rentals for their distribution fees. Chaplin and First National divided the remaining net profits equally.8 A key if often overlooked feature of the agreement was that after five years, the rights to his First National films reverted to Chaplin. From this point on, Chaplin arranged personally to own the rights to every subsequent film he made in the United States, through to Limelight in 1952. That is a major reason why we presently enjoy excellent prints of all the films from the First National period on: Chaplin knew his films were valuable, and he made sure they were well cared for.

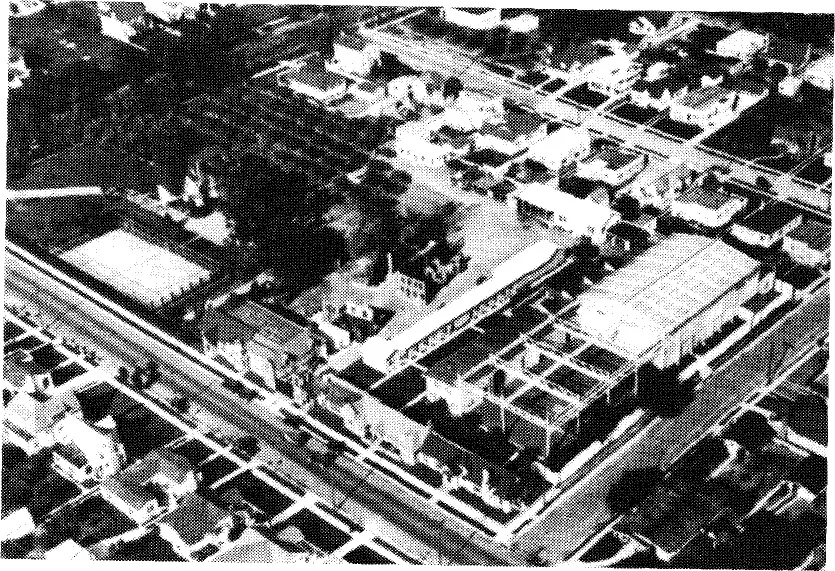

Chaplin had two more tricks up his sleeve. The first was to invest part of the fortune he had accrued by building his own studio. In 1917 he purchased four acres of land in Hollywood, located south of Sunset Boulevard, east of La Brea Avenue, and north of Du Longpre Avenue, for $34,000. A house and tennis court already existed on the north of the property; to the south Chaplin built a studio that included two open stages, dressing rooms, offices, buildings for wardrobe, painting, and carpentry, a projection room, and even a film-developing laboratory. To reduce friction with his residential neighbours, he lined the western edge of his property, along La Brea, with building exteriors that looked like English cottages.9 Nearly all the city we see in City Lights was created on this site.10

Aerial photograph of Chaplin Studio, 1922-3, during the shooting of A Woman of Paris

As Chaplin was fulfilling his First National contract, the movie business was consolidating. Early in 1919 rumours began flying that Paramount/Famous Players Lasky was planning to merge with First National, Chaplin's distributor, in part to combat spiralling star salaries. Led by Adolph Zukor, Paramount went on to become the first vertically integrated movie studio - a company that made films, then distributed them to theatres it owned. To counter this growing threat, on 15 January 1919, three of the most famous stars of the day - Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks, and Mary Pickford - and the most widely known director, D. W. Griffith, joined to form United Artists, a company designed to market and distribute films that each of these artists produced independently. This final move made Chaplin an independent film-maker. All eight feature films he shot after fulfilling his First National contract, starting with A Woman of Paris in 1923 and stretching through to Limelight in 1952, were distributed through United Artists. Of them, the final shot of City Lights, the fourth film, and the opening shot of the fifth, Modern Times (1936), stand exactly in the middle.

3 Three Preceding Features

The first three United Artists films – A Woman of Paris, The Gold Rush (1925), and The Circus (1928) – established the groundwork and provided a backdrop for City Lights. All were feature-length films, with Woman running 7,577 feet, Gold Rush 8,555 feet, and The Circus a briefer 6,500 feet, each longer than Chaplin's longest film before these, The Kid (1920, at 5,250 feet). City Lights runs 8,093 feet.

A Woman of Paris was a departure for Chaplin, in part designed to show his versatility as a director and to enhance his reputation. Because tragedy maintains a higher cultural status than comedy, the successful comic sometimes hopes to play Hamlet. Witness Woody Allen's Interiors (1978), his Bergmanesque follow-up to Annie Hall (1977)....

Table of contents

- Cover

- Fm

- Title Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- 1 The Ending

- 2 Chaplin's Hollywood Roots

- 3 Three Preceding Features

- 4 Divorce and Tax Problems

- 5 Hannah

- 6 The Challenge of the Talkies

- 7 Refining a Story

- 8 The Production Record in Perspective

- 9 A Troubled Production: To November 1929

- 10 The Production Clarifies: From November 1929

- 11 Chaplin, the Jazz Age, and Submerged Autobiography

- 12 The Narrative Structure

- 13 The Opening Scenes: A Closer Look

- 14 Contrasting Moral Universes

- 15 Final Sequence: Part One

- 16 Final Sequence: The Heartbreaking Ending

- 17 Release and Reception

- 18 The Legacy of City Lights

- Notes

- Credits

- Bibliography

- eCopyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access City Lights by Charles J. Maland in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film History & Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.